'Every Ali obituary I read made the point that he 'transcended his sport' -- a reference to the many battles he fought with America even as he fought in America.'

'What the obituaries leave out is that Ali equally transcended the boundaries of geography and of information -- as witness the Chennai teen who assimilated that most mobile of fighters through still images shorn of context.'

Prem Panicker salutes the man who 'shook up the world'.

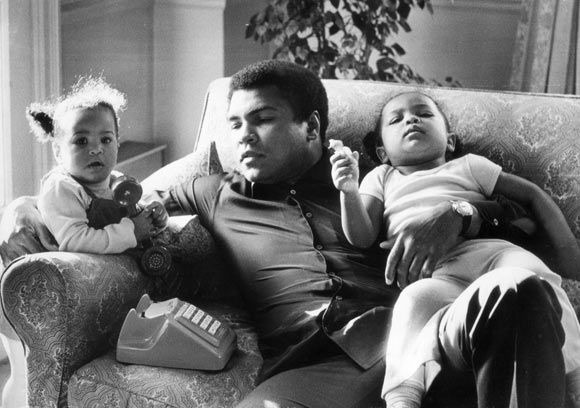

My father picked his way through literature the way David Livingstone explored Africa, through a series of serendipitous lurches that took him towards his destination, more by accident than deliberate design. Availability and affordability dictated his choices.

Thus, every other Saturday, he went from work direct to Moore Market, an ancient quadrangular British-era building in Chennai where you could buy anything from parakeets to perfumes. And secondhand books, from the over 100 stalls that lined one entire wing.

Through a series of complex calculations -- how much for Scissors cigarettes for the next fortnight, how many times would he have to pick up the peer-group tab for tea and vadas, etc -- he arrived at how much he could spend on his favorite indulgence. Through careful selection and ferocious bargaining, he came away with a bagful of books, some mapping to established interests, the rest purchased because 'they looked interesting, and were cheap.'

Mom and I knew the schedule. Thus, on his Moore Market Saturdays, mom made sure there was hot tea and 'tiffin' waiting -- that was her way of ensuring first dibs on the best picks. And on that day, I eschewed cricket, watered the plants without needing to be reminded, and sat out in the garden with some random textbook -- a fortnightly show of zeal calculated to get into his good books, and thus to get my hands on his good books.

One evening he came home with a selection that included a couple of books that were out of the box, even by his idiosyncratic standards: George Plimpton's Paper Lion and A J Liebling's The Sweet Science. 'American football?' mom asked, her eyebrows semaphoring incredulity. 'BOXING?!!'

'Well, you know -- Ali, so I thought...'

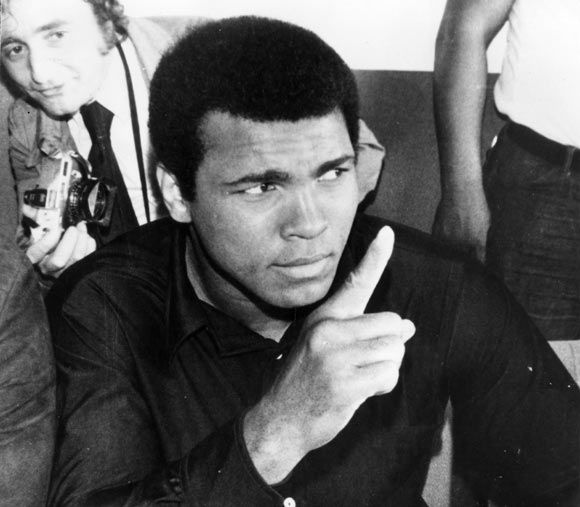

I ended up with the Liebling book that weekend -- the first real sports book I read, also the first time I realised that sport could make for great literature. As Liebling discussed the 'laying on of hands' that is the essence of boxing, and described with exuberant felicity a contest between Archie Moore and Rocky Marciano, the grainy black and white images of Ali I had painstakingly collected and filed alongside anodyne newspaper accounts of his various fights began to make acquire shape, and definition, and context.

My world back then was a place I struggle to explain to my two young nieces: No internet, no wikipedia, no WhatsApp groups for shared interests, no easy access to books, no idea even of what books were being published in the genres that interested you.

The world was a borrowed jigsaw puzzle, one where you were never sure if all the pieces even were in the box, even. You assimilated it and assembled your worldview in disjointed segments, the way I explored Ali -- an image here, a featureless report there, fragments of grainy footage in the newsreel that preceded the feature film of the day, a catchy Johnny Wakelin ditty (external link) heard on Radio Ceylon's top ten programme, a chance-met issue of Life magazine that featured a Norman Mailer epic, Ego (external link), on the first of the Ali-Joe Frazier trilogy... None of these coalesced into a recognisable composite; all of it left spaces for the imagination to fill as it will.

Every Ali obituary I read over the past 24 hours made the point that he 'transcended his sport' -- a reference to the many battles he fought with America even as he fought in America. What the obituaries leave out is that Ali equally transcended the boundaries of geography and of information -- as witness the Chennai teen who assimilated that most mobile of fighters through still images shorn of context (Back then, I didn't know there were boxing categories other than heavyweight; equally, I knew little of the Vietnam war and cared even less).

A fortuitous opportunity to join Rediff at its inception introduced me to the internet and -- cue magic -- the archives of international publications; a serendipitous transfer to New York put me within 10 blocks of Strand with its 'eight miles of books' and, a half block away, Barnes and Noble with its endless shelves of DVDs.

Boxing was what I had read first, so boxing is what I explored the most.

As I accumulated books and printouts of boxing stories by the best, the story of Ali began to acquire personal relevance. Sports-writing has limited shelf life -- what, after all, is the point of reading a blow by blow of a match that took place decades ago? For a wannabe sportswriter, that is both problem and challenge -- how do you anchor a fleeting event and give it a relevance beyond its immediate life?

Boxing, which more than most other sports sparked a dazzling efflorescence of enduring literature, provided answers -- and Ali was central to most of it.

Context of a different sort came from my day job of following Indian cricket. It was a time when the dark shadow of corruption and impropriety had fallen over the game, obscuring all that we had earlier delighted in.

Shortly before I went to the US, I had the dubious privilege of an 'off-record' conversation with cricket's anointed deity in course of which he laid out, in great detail, the backstage machinations of players and administrators. Why 'off record'? I asked then. Why don't you speak out, get all this before the public, front a clean up? 'Nothing will happen,' he said. 'It goes too deep, and I have my career to think of.'

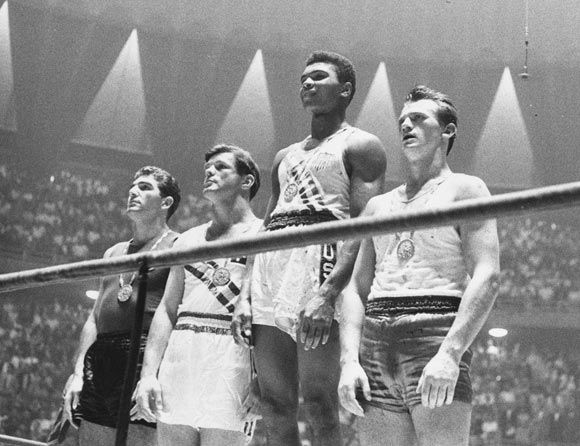

Just like that, Ali slotted into place as the antidote to the apathy that we wear as a protective cloak. When he defeated Sonny Liston in Miami in February 1964 to claim the World heavyweight title, Ali was barely three years into a professional career that stretched, pregnant with infinite promise, ahead of him.

Yet, when a reporter cornered him next morning with a question on his affiliation with the Nation of Islam, Ali had the integrity to stand up for his right to believe as he pleased.

'I don't have to be what you want me to be,' he said then. 'I am free to be what I want' -- an unyielding stance that over time empowered, among many others, UCLA freshman Lew Alcindor to become Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and to forge a personal identity distinct from his on-court wizardry.

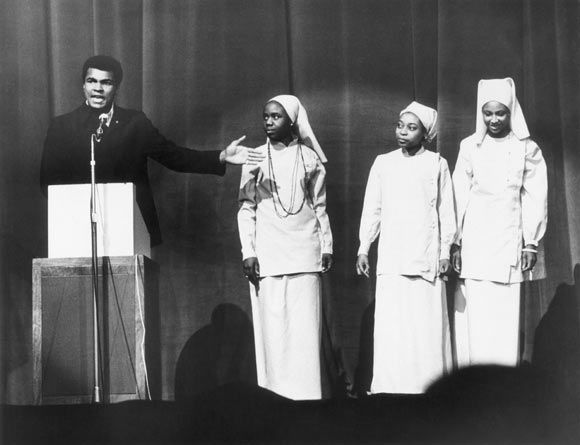

If Ali's open avowal of a Muslim identity offended the majoritarian white Christian community (even the august New York Times, for the longest time, refused to call him by his assumed name, Muhammad Ali), he went one better when, in March 1967, he refused to be drafted into army service.

He had no quarrel, he said, with the Vietcong. 'They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn't put no dogs on me, they didn't rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father... how can I shoot them poor people?' he demanded, while choosing physical incarceration over the prison of his conscience.

In Ghosts of Manila, the brilliant, contrarian Mark Kram argued that Ali's anti-war stance was a sham. He pointed out that Ali had already failed an army-mandated test (his IQ was rated 78), and had been deemed unfit for military duty. He could have used that to avoid service (as the US supreme court did four years later, when it overturned Ali's conviction 8 votes to zero); he could even have enlisted and been assigned some anodyne role while continuing to box (From Frank Sinatra to Marilyn Monroe, 'entertaining the frontline troops' was a staple of such token patriotism). Ali's objection was mere grandstanding, Kram wrote.

Kram makes a point while missing the point: Ali could have chosen the easy way out, and continued to practice the sport he was just beginning to redefine. Instead, he chose the harder option: He took a stand against the war itself, not merely the question of his own participation in it.

Stripped of title and passport, he carried his anti-war message and his fight for racial justice to college campuses across the country, and offered himself up as the lightning rod for growing disenchantment, even if it meant he never got to box when he was at his physical peak. 'Draft Beer, Not Ali' was a slogan that defined the time.

As I was writing this, a friend on Twitter told me (external link) he felt underwhelmed by Indians writing on Ali -- after all, we had never lived Ali's life.

True, to a point -- but then, we didn't have to live in ancient Greece to internalise the story of Achilles either.

Ali the public figure willing to risk his all on a matter of principle is a symbol that transcends nations and spans generations. To an Indian used to public figures toeing the line of what is politic rather than what is right, Ali is the counter-example, the antidote for public apathy and professional cynicism.

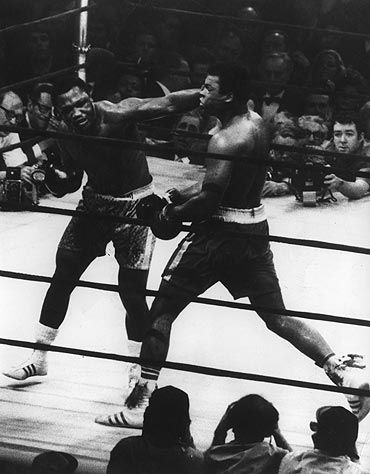

Ali's conscience -- the very thing that over time alchemised a brash iconoclast into a universal icon -- also set up one of the enduring what-ifs of sport: What if the period between 1967, when he was stripped of his title, and 1971, when he met reigning heavyweight 'Smokin' Joe Frazer at Madison Square Garden, had not been lost?

Prior to his suspension, Ali's career had backlit by wins over such pugilists as Sonny Liston (first, in February 1964 and again, via the much-discussed first round 'Phantom Punch' knockout, in May 1965), and also the November 1965 dismantling of Floyd Patterson.

In the 1964 fight against Liston, Ali had already demonstrated the essence of his art -- the carefully calibrated trash talk that, for all its seeming randomness, was a means to a predetermined end, equally a part of Ali's unique boxing grammar alongside the dancing feet and the triphammer left (see this commemorative post external link).

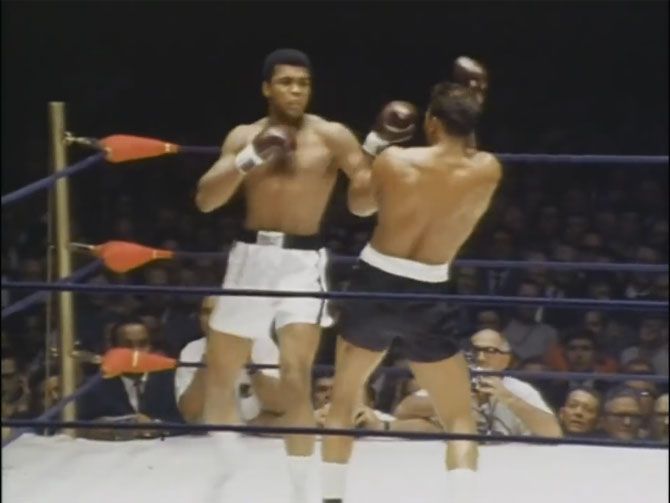

But nothing so gloriously exemplified Ali's art as his November 1966 three-round demolition of Cleveland Williams.

Here, watch him dance (external link) with the casual aplomb of a Nijinsky carrying a leaden-footed neophyte through a complex pas de deux.

It is an eight minute fight that showcases how completely Ali reinvented his sport: The hands held low in defiance of boxing's basic 'keep the guard up' tenet; the quicksilver feet and 'catch me if you can' devilment that opened up the ring and reduced his opponent to chasing a chimera across an endless prairie; the awareness of time and space that allowed Ali to glide into and slide away from punching windows before his opponent could gather his wits; the ability to hit while back-peddling, again defying the canon that a boxer has to set himself up two-footed to get shoulder and body into the punch; the flickering left jab that he used like a pointillist's brush to etch agony in his opponent's eyes; the overhand right so fast it deceived the watching eye; the 'Ali shuffle' (see around 1:38) that confused the opponent and set him up for a devastating drumroll of combinations to face and body...

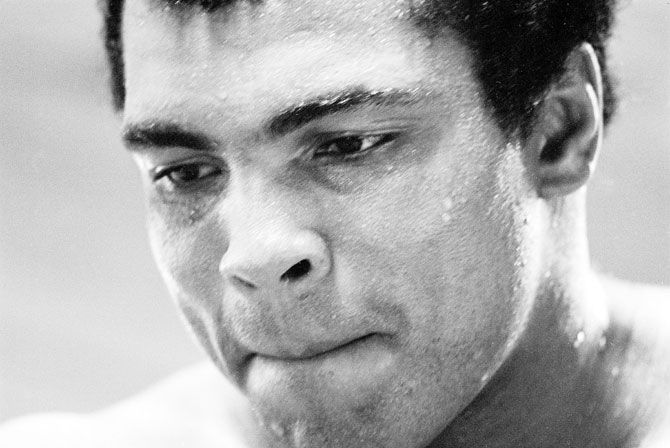

Then, he was perfection. His physician Ferdie Pacheco said of the young Ali that he was the most perfect physical specimen there ever was, from both an anatomical and an artistic standpoint. 'You just couldn't improve on the guy,' David Remnick, whose King of The World is the definitive Ali biography, quoted Pacheco as saying. 'If someone came from another planet and said, give us your best specimen, you'd give them Ali. Perfectly proportioned, handsome, lightning reflexes, and a great mind for sports.' Toni Morrison, who edited his biography, called him a beautiful warrior. 'His grace,' Morrison wrote, 'was almost appalling.'

It's all there, that deadly, lethal beauty, captured in this one fight. It's there, a style of boxing that borrowed from the art of the toreador. Ali used his shimmying body as cape, to tease and beguile his opponent to madness, before applying the coup de grace, usually with that overhand right cross.

The style entranced a growing legion of fans, and baffled the best pundits of the day. Alberto Moravia once told Mark Kram that Ali 'forces you to see in a new way.' And Liebling, doyen of fight writers, puzzled over a performance from that period and declared that it was 'attractive, but not probative. Clay has a skittering style, like a pebble scaled over water.' He cannot last, was the sub-text of that assessment.

It was a style never seen before -- and it was never seen in its full glory after, either, for when Ali returned after the lost years, his legs had lost much of that spring. He still danced, but in snatches -- a Nijinsky who remembered the ballet, but could only pull off the odd set-piece with a semblance of the old panache.

When Ali's legs lost the knack of perpetual motion, the ring shrank back to its natural size, and his opponents began correspondingly to gain in heft. The erstwhile butterfly could only float intermittently; he could now be caught, and even if he could still sting like a bee, he could in his turn be cut, hurt, damaged.

His career fell thus into two neat categories: 29 of them in the period before his suspension, and 32 of them in the second half of his career all the way to anti-climactic losses to Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick. But of those 32, two fights defined Ali -- and the sport of boxing -- for all time: His eight-round dismantling (External link) of 'Big George' Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire on October 10, 1974 and the third episode (external link) of Ali's storied rivalry with Frazier, October 1, 1975 in Quezon City, The Philippines.

The first was a purely technical challenge. Both fighters were evenly matched in terms of height, and Foreman carried two extra kilos of muscle. In his most cerebral fight, Ali solved the problem by resting on the ropes and absorbing Foreman's tremendous punching power, draining the bigger man of both breath and heart before unleashing a stunning five-punch combination that knocked Big George off his feet and onto the canvas.

The story of that fight is the story of the punch Ali did not throw as Foreman went down -- because, he said later, it would have spoilt the beauty and integrity of the knockdown.

The second, the Thrilla in Manilla, was a ticket for two to hell. It featured the polar opposites of boxing as sport: Frazier the devastating puncher, who had honed his lethal weapons by punching bricks hung in a bag from a tree, and perfected his combinations hammering away at sides of beef in the slaughter house where he worked.

In the opposite corner, Ali, for whom beauty was paramount, and who eschewed brutal training methods in favour of the heavy bag, the speed bag and the rope.

For sheer drama before, during, and after the fight, it has few equals in boxing -- or indeed, in any sport. And it featured a round -- the ninth -- that showcased boxing in all its awful, bloody, appalling beauty. Mark Kram wrote the story of that round best:

'With the ninth, Ali fought one of the best rounds in history and brought the crowd to its feet with a shock and to such a roar that you couldn't hear the bell. Joe's head seemed stuck to Ali's gloves as rights and lefts, cringing rounds of volley, caromed off Frazier's head, then uppercuts, often used against low fighters, that jerked his head up as if it were being snapped up by rope. His face was melting into ruin, his eyes closing like shades being drawn ever so slowly. Joe wasn't just being hit, he was taking beast licks. Just past the middle of the round, Ali nailed up a picture for the ages. In the center of the ring, with Joe rolling in like an angry wave, Ali got off a design of punches that can only be called incomparable, took the breath away from any student of the game. While backpedaling, the worst, most ineffectual punching position, he loosed a quartet of flush hooks like perfectly timed and blurring explosions, the kind of fire patterns talked about but never before seen; these weren't just punches; it was dark, magnetic Goya.'

Frazier could not answer the bell for the 15th round; famously, Ali at the end of the 14th had already given up, and it was moot whether he could have risen to the bell had his opponent not thrown in the towel. Years later, Kram asked Ali to review the fight on DVD. Ali refused. 'I don't wanna look at hell again,' he said.

He didn't need to -- he had already, though he wasn't aware of it then, fallen through the trapdoor of Manila into the special hell that waits for boxers who take one pounding too many.

In a 12-month span neatly book-ended by Foreman in October 1974 and Frazer a year later, Ali had fought 63 punishing championship rounds, besides endless rounds of sparring when at his insistence his partners battered his body to condition him to absorb punishment.

That grueling year took its toll. The early signs of brain damage were already apparent when Larry Holmes respectfully carried him for 10 rounds in Ali's penultimate fight, and when Berbick mauled him two months later to write finis to a storied career.

Ali was sui generis a sportsman with skills so unique they couldn't be adequately measured against conventional rivals. What if, the hype machine wondered, as it came up with a computer-generated fraud of a fight against Rocky Marciano (external link) in 1969.

A decade later, DC Comics produced a 72-page feature where Ali takes on Superman before an audience that included The Beatles, Michael and the rest of the Jackson 5, Sinatra, Raquel Welch, Orson Welles, Woody Allen, US Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, and Pele.

It is a measure of the irony that abounds in sport that a man who defined his age with dancing feet and quicksilver tongue was reduced, for the latter half of his life, to a stumbling, palsied, stuttering parody of himself. And it is equally a measure of his accomplishment that even the sight of an Ali whose once-lethal hands now trembled with the effort to hold up the Olympic flame (external link)m in Atlanta did nothing to dim the enduring image of physical perfection.

Ali, who talked his fights well before he fought them, also talked of his epitaph four decades before death made it necessary.

In 1975, he told Playboy magazine (external link) all that he would like to be remembered for. 'And if all that's asking too much, then I guess I'd settle for being remembered only as a great boxing champion who became a preacher and a champion of his people. And I wouldn';t even mind if folks forgot how pretty I was.'

Perversely, though, the words that come to mind when thinking of Ali in the wake of his passing are those of Jimmy Cannon, eminence grise of boxing writers of the fifties and sixties. Cannon was contemptuous of Ali, whom he saw as a brash arriviste, and yet the words he used for Joe Louis are the ones that best define Ali:

'He was a credit to his race -- the human race.'