The bunker was built in 1942, but remained a secret to Samara's citizens until 1990, when it was uncovered and later turned into a museum.

As the Russian city of Samara gears up for Saturday's England-Sweden clash, some fans have been taking time out to discover a darker side of the city hidden underground.

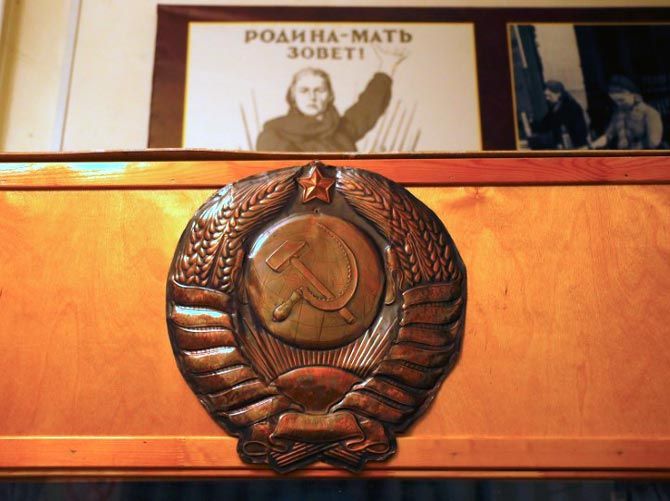

Hundreds of visiting supporters have been queuing up to visit Josef Stalin's bunker - chambers dug out underneath the southwestern city to protect the Soviet leader from a Nazi German assault that never came.

"You get goosebumps. You can't imagine all of that happened just here and only a few years ago. It is a very good experience to take back to our country," said Mexico fan Josue Resendis.

Supporters, many still wearing their team's tops, carefully walk down flights of narrow stairs until they are 37 metres (120 feet) below the soccer celebrations.

"To think that a place that today shows so much happiness has had a past in which children, women were carrying arms and building planes in order to have one human being fighting another human being because of an ideology...” Thiago Andrade from Brazil said.

“It is good that it is over and that things in the world are now solved in a different way.”

The bunker was built in 1942, but remained a secret to Samara’s citizens until 1990, when it was uncovered and later turned into a museum.

Its walls were built to withstand a direct hit from an aerial bomb and held enough provisions to feed Stalin and his entourage for up to five days.

During World War II, Samara - then named Kuybyshev - was chosen to be the alternative capital of the Soviet Union should Moscow fall to the German troops, and the shelter was meant to be the headquarters of the Armed Forces, led by Stalin.

He never had to use it.

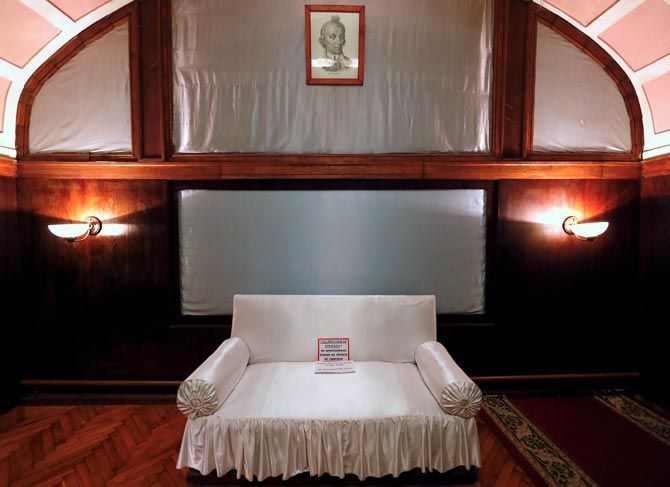

The bottom floor contains two rooms: the main chamber which could accommodate 115 people and was meant to serve as meeting room, and Stalin’s personal chamber, the tourists' favourite.

Here they can sit at Stalin's desk, pick up the handset and "call the Kremlin".

Legend has it, according to a museum guide, that the phone line used to be live until a French tourist called home and ran up an extortionate bill.