The Glazers are unlikely to ever be liked, let alone loved, by fans of Manchester United. The fiercely private American family that bought the famous English soccer club 10 years ago has been widely depicted by the team's fans and the British media as seeking to bleed the club dry after leveraging it up with debt.

Yet the Glazers are now assuaging some of their critics as the club says it will bankroll new player signings and is in a position to return to Europe’s biggest cup competition after failing to qualify in 2014 for the first time in 19 years. Crucially, their transformation of United into a commercial cash machine may give them an advantage over rivals.

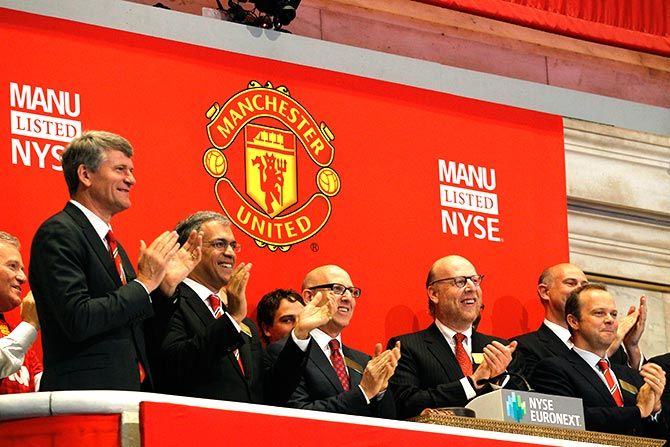

There have been modest signs of hope for investors in the club's New York-listed shares, which have outperformed the S&P 500 so far this year, gaining 2.3 percent against the index’s rise of 1.7 percent as revenue and cash flow are expected to climb. The shares have lagged the market since United's 2012 initial public offering.

"My view is Man United are better off for the Glazer's ownership. Building the commercial engine they've built will continue to serve the club well," said Philip Hall, managing partner at Spotlight Equity Partners, who advised other U.S investors on purchases of Liverpool and Sunderland soccer clubs.

Last week, consultancy Brand Finance declared that Manchester United had regained its position as the most valuable soccer brand in the world in annual rankings, moving up from No. 3 in 2014. The value of its brand had soared 63 percent in the past year to $1.2 billion as its Executive Vice-Chairman Ed Woodward and the Glazers "capitalised on the brand's growing power to establish a worldwide fan-base and a range of sponsorship deals unrivalled in their number and value," according to Brand Finance CEO David Haigh.

United and the Glazers - the family rarely make any public statements - declined to comment for this story.

On the pitch, this season's performance improved enough to get United fourth place in the English Premier League, up from what for United was a shockingly low seventh in 2013-14.

While still unacceptable to fans given the side has been synonymous with winning trophies for much of the past two decades, the improvement is enough to secure a play-off round for the UEFA Champions League, the continent's blue-riband competition. With that comes more match-day revenue from extra games, increased sponsorship money, additional club merchandise sales, and a boost to TV income.

But crucial to growth is the way in which United is using the allure of what it says are 659 million people following the club around the world to secure sponsorship deals.

A world record 750 million pound ($1.17 billion) 10-year kit deal with Adidas, signed last year, underlined United as commercial leaders in soccer. That followed a seven-year $559 million shirt branding deal with General Motors' Chevrolet.

Commercial income will eventually make up over half of revenue, up from 29 percent when the Glazers arrived, brokerage Jefferies says, pointing to the club's 17 global sponsors now versus 10 in 2012, and 95 total categories earmarked for marketing from 40 three years ago.

That could give it a leg up on rival clubs because the increased commercial revenue allows United to push up wage and transfer bills while remaining within its means. That satisfies new regulations designed to prevent clubs from spending more than they earn in attempts to buy success.

The club's fortunes are being shaped at sales offices in London and Hong Kong.

At an unmarked building near the Ritz hotel in London's posh Mayfair district, United employs around 60 people to win new commercial deals.

United's sponsorship appeal stretches from beer, wine and watches to tires, paint, noodles and office equipment – across partners in many countries. It even has telecommunication company sponsors in Azerbaijan and Thailand.

As part of the Adidas deal, the club has retained retail rights to its own store, online sales and product licensing and will likely expand and outsource to third parties and take a royalty, Nomura analysts say.

A new digital media platform has also been slated.

United's commercial progress led the club to raise its full-year earnings forecast last month.

And Jefferies analysts see United's revenue growing by a third to 521 million pounds in the year to June 30, 2016.

New York-based hedge fund manager Ron Baron, who owned 40 percent of the shares not controlled by the Glazers at the end of last year - told CNBC in January he expected to double or triple his money on United over the next four to five years. He declined to comment for this article.

Some smaller investors are also hopeful. "There's always the chance that the solid and incalculable value of the Manchester United brand and related intangible worth will prevail, and ultimately reflect in the stock's performance," commented Steve Schmelkin, a senior director of the Clutch Group, a legal services company, who says he owns a small stake.

Malcolm Glazer, the family patriarch who made his fortune in real estate and stocks, bought United in May 2005 for 790 million pounds, after entering the sports business in 1995 with a takeover of American football team, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

The leveraged nature of the deal – United took on loans of 525 million pounds to finance the acquisition – by a businessman and his family who were unknowns in the UK – made many United supporters very angry.

An effigy of Malcolm Glazer was burnt in the street during mass protests, and his death last year was celebrated by some on the terraces. The three of his six children, Avram, Joel and Bryan, who have managed the investment since Malcolm suffered a stroke in 2006, have also had a bad reception. Fans chanted "die, die Glazers" at the club’s Old Trafford ground, forcing family members to escape in an armoured police van on one occasion.

A dip in performance after legendary manager Alex Ferguson retired in 2013 hasn't helped relations with some fans who allege the club has been more interested in servicing its debt rather than investing in new players.

And despite the improved prospects there is plenty that could go wrong.

The worst case scenario would be if expensive new players fail to perform, the club suffers an early exit from the Champions League, and it falls down the Premier League table. Player costs would bite into financial results and the club could descend into a longer-term decline.

For shareholders there is also a danger the Glazers sell United shares when they need to raise money as has happened in the past. That could hit the share price.

In a statement to mark the 10th anniversary of the Glazers takeover, the Manchester United Supporters Trust (MUST), which has campaigned against the Glazers' control, said that while it's impossible to imagine worse owners there are signs the club is seeking to improve relations with fans.

"Despite the huge damage inflicted over the last 10 years, things are undoubtedly beginning to look positive again in 2015," conceded MUST CEO Duncan Drasdo.

The thawing only goes so far, though. One investor in the stock declined to comment for this article because he feared being targeted by anti-Glazer supporters.