'The ball barely made it to the hole, giving rise to a heady exhilaration and bemusement that only Woods' adroitness could -- and perhaps still does -- invoke.'

Dhruv Munjal on the greatest golfer of all time.

Throughout his storied career, Tiger Woods has routinely served up staggering reminders of his paranormal talent: The now legendary hole-in-one on the 14th at the 1996 Milwaukee Open, his first professional tournament; the 60-ft, triple-breaker putt on the 17th at Sawgrass -- the most notorious green in golf -- during the 2001 Players Championship; the chip on the 17th at the 2008 US Open, an astonishing shot considering Woods played the entire four days -- and won -- with a battered left knee.

But there is one moment that lingers in the memory more than most. It came at the 2005 Masters, the only tournament Woods ever dreamt of playing and winning as a golf-mad kid growing up in Cypress in southern California.

Almost 12 years ago, as lengthy shadows spread across the scenic Augusta National, Woods conjured up the kind of golfing genius that often left his competitors gasping for air and gaping in befuddlement.

As his intense duel with Chris DiMarco headed for a close on the final day, Woods sprayed his drive on the par-3 16th into the rough.

He still managed to make birdie, hooking the ball from left to right and then on to the slope with his pitch.

The ball barely made it to the hole, giving rise to a heady exhilaration and bemusement that only Woods' adroitness could -- and perhaps still does -- invoke.

Later in the day, he won his fourth Masters.

Any chronicle of The Masters in the last two decades would be incomplete without mention of Woods.

In the nine years between 1997 and 2005, Woods won four times at Augusta National, a record he shares with Arnold Palmer.

Only Jack Nicklaus has done better at the hallowed course, winning a monumental six times.

But perhaps none of Woods' four wins was as impressive and far-reaching as his first, a time when the golfing world was fully confronted with Woods' tremendous potential.

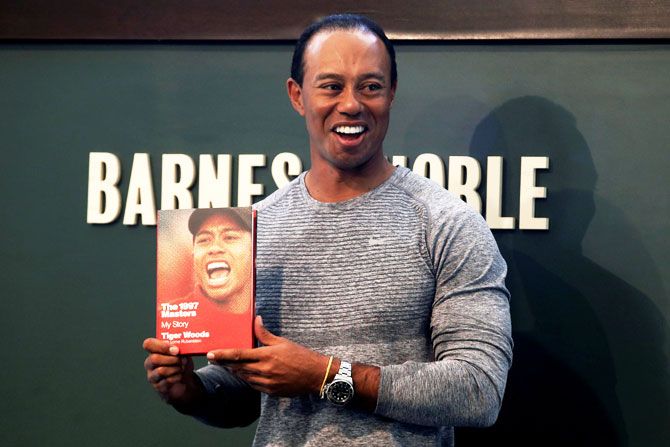

His new book, Unprecedented: The Masters and Me, co-authored by golf journalist Lorne Rubenstein, is a belated celebration of that epochal victory in 1997, which was also his first major as a professional.

Woods wasn't really an undiscovered specimen back in 1997.

Coming into the tournament, he had won three straight US Junior and Amateur titles, and was already being touted as that once-in-a-generation athlete who possessed the kind of virtuosity that often redefined a sport in unfathomable ways.

By the time the Masters concluded that Sunday, that prophecy had come true.

The experts vehemently agreed; the naysayers reluctantly applauded.

Unprecedented's allure lies in its writing. Woods dons the cap of co-writer not as the colossal golfing sensation that he has come to be known as since, but as the golf-worshipping 21 year old who was awed by the majestic environs of Augusta and the mavericks who roamed it just like any other regular watcher.

A tad embarrassed at his own naivety, Woods talks about his first meetings with Palmer and Nicklaus, the maiden round of golf he played with Nick Faldo, exchanges with Nick Price, learning the secrets of the short game from Seve Ballesteros and José María Olazábal, and playing with friend and mentor Mark O'Meara, or 'Mo' as he still fondly calls him.

Funnily, O'Meara, almost 20 years Woods' senior, won The Masters only in 1998, and it was Woods who helped him put on his Green Jacket.

A majority of the early part of the book is an attempt at trying to bring the reader to understand the grandiosity of Augusta -- what sets the course apart, why Lee Trevino never won there despite winning all the other majors twice apiece, and a much-deserved tribute to the wondrous par-3 12th.

Where Woods and Rubenstein deserves ample credit, though, is for their quite brilliant simplification of otherwise ponderous golfing jargon -- they break down the technicalities superbly.

In the chapter that elucidates his choice of driver that week, Woods writes, 'The idea was to use the gear effect that you could get then with permission. The heads were small enough compared with the size they would become, and they had enough bulge and roll so that if I made a normal swing intending to hit the ball off the toe, the ball would draw... I could shape the ball any way I wanted.'

Rubenstein writes with a light touch, recalling every little conversation and phase of play in resplendent detail.

A warm hallmark that emerges from the book is Woods' relationship with his father, Earl. Woods writes about how he spent hours playing golf with him at the Navy Golf Course in Cypress as a child, and how Earl's advice on his putting grip helped him recover from the shambolic 40 that he had shot on the front nine during the first round at Augusta in 1997.

He would win the tournament by a record 12 shots.

Several years later, after beating Colin Montgomerie in a playoff to win the 2006 Open Championship, Woods sobbed inconsolably, hugging caddie Steve Williams in a way never seen before.

The victory was his first after Earl had died in May that year.

In other parts, Woods deserves applause not so much for his writing, but for his courage.

Woods highlights the problems of racism in golf candidly. '... as much improved as race relations were while I was growing up I could still feel an atmosphere of exclusion when I went into some country clubs or restaurants,' he writes.

The Augusta National Club remained closed to black players for a number of years; Woods is still the only non-white golfer to have won there.

Where the book mildly disappoints is in Woods' failure to talk about his other three triumphs at Augusta -- surprisingly, they find no mention at all.

Another criticism is his protracted prelude to the actual four-day event in 1997. The run-up is maybe too arduous, leaving barely hundred-pages worth space for the tournament proper.

Even then, Unprecedented takes you away from Woods' treacherous personal past and offers you a much-needed glimpse into the mind of a master golfer, the phenomenon that now delights and deceives in equal measure.