'No country can go from zero to hero at the Olympics.'

'A hundred Indians now feature in the world's top 25 and that's progress,' says Shekhar Gupta.

We broadly share one of the two views on Olympic sports. The first is the fan's view, at this point in an overwhelming majority, that Indian contenders are trying their best in spite of many handicaps and it will be wonderful if they brought at least a few medals home.

The second, let's call it the Shobhaa De club, currently a very silent minority, that believes Olympic sports are just a selfie-and-goodies junket for Indians, so why waste the money and emotion and allow ourselves to be humiliated by our participants and officials.

You will be surprised if I said that both are right -- given the anger over Shobhaa De's publicly stated view. I shall complicate it further by adding that both are wrong as well.

Why each is right, is simpler to understand. It is perfectly natural for a nation to expect glory at the greatest stage of world sport and to be disappointed when it eludes you. Why both are wrong, as I said, is complicated. Particularly in these hyper-nationalistic times.

The flaw in both, optimism and sneering, lies in defining success as medals. I write this on the day track and field events begin in Rio, and am sobered by the realisation that these Olympics haven't yet gone as well as the last one at London.

But no nation, no team goes from zero to hero in Olympic sports. We cannot begin with the history of one individual gold, three silver and nine bronze medals over 96 years of participation and set the bar for our teams up there.

To now say that from being such outsiders we should dramatically jump to a place at least in the top 25 of the medals tally (our highest rank so far was 50, at Beijing) just because we are number one or two in Test and one-day cricket, we've been the fastest-growing economy over the past couple of years, claimant for a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council and a full member of the Missile Technology Control Regime is as delusional as claiming that our economic growth has overtaken China's.

Reality check: Sri Lanka's per capita GDP is about 50 per cent higher than ours, in spite of a withering 25-year war with itself. It follows, on the optimistic side, that just as our growth rates are picking up and will, over time, narrow the gap with those ahead of us, our sporting performances should be improving faster than the rest too.

Again, it will narrow the gap, but not make us world-beaters. Winning medals in real Olympic sports is tougher than for the Anushka-smitten Salman 'Sultan' Khan who begins training at 30 and sweeps the golds.

It takes years, in fact more than a decade's training, for a wrestler to even win qualification for the Olympics. You want an idea how tough it is: Narsingh Yadav won a spot at the very end of the qualification process by winning a bronze medal at a world championship.

For athletics, the general standard is beating the sixth position at the last Olympics, which is a lot to ask of in India, where most records have generally failed to enter the top 25.

Even hockey needs a continental championship -- which is how we qualified -- or a tough qualification tournament. This explains why India was absent in Beijing and Pakistan couldn't make it to Rio.

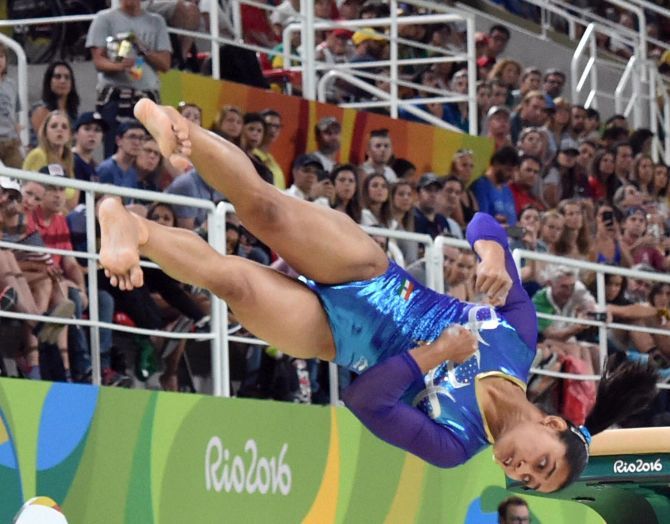

A contingent of around 120 in Rio means overall Indian standards have improved, not just in areas of our traditional strength, including hockey, wrestling, boxing and shooting, but also in archery and, most remarkable of all, gymnastics.

A woman gymnast earning qualification for Olympics and vaulting her way to the finals is a truly remarkable achievement for a country where a majority of 25 year olds would struggle to touch their toes.

Barring two swimmers who got ‘invitations’, the rest have qualified and, unlike in the past you can no longer have domestic coaches fix your performances. The process is now tightly regulated and controlled, and doping is enormously tougher. No country can suddenly have world-beaters unless you first start breaking into the top-50s, 25s and eventually 10s, where medals become possible.

Until Seoul in 1988, the number of Indians in the world's top-25 was in a single figures (hockey apart).

Today, it is more than 100 spread across a large variety of disciplines, although the largest numbers will be in contact sports and shooting.

At least 30 Indians will now feature in the top -10 of their respective disciplines and a brilliant handful in the top five, from Saina Nehwal in badminton (who has twice been at the top recently) and the hockey team at five.

There is still no guarantee of medals. We have no Michael Phelps, but the fact is, there is only one of that kind in the world.

But do we fret over that, or the fact that a rare Indian has earned qualification for swimming (Shivani Kataria qualified this year; we had one in 2008 too).

Our timings have been improving lately, but traditionally, so bad has our swimming been that in many of the categories our men's timings lagged women's at not just world levels, but even at Asian levels.

This isn't a sexist statement because men and women compete in their respective categories.

Given such a massive gap, there are just a few ways we would win a medal. One, if a prodigy rises like, say, a Mary Kom or Saina Nehwal. Or if associations or committed coaches help their wards prepare brilliantly in a discipline of traditional Indian skill or strength, like hockey and contact sports in lighter weight categories, like Sushil Kumar, Vijender Singh and Yogeshwar Dutt.

Or a self-motivated prodigy with training wherewithal, whether personal as with Abhinav Bindra or institutional as with Rajyavardhan Singh Rathore.

To expect anything dramatic with this talent base is wishful. But to diss the rapid progress made in the past 25 years, since reforms gave us improved economic growth rates, is a fantasy.

The fact is, the sub-continental lifestyles, physique, carbohydrate-laden diets over millennia do not make us natural sportsmen. It is a cruel fact, but Bangladesh, now rising as a cricket power, is the largest nation by population to have never won an Olympic medal.

And Pakistan has seen only two, an athlete and a judoka qualify.

You can laugh at South Asian-level competitions, but with similar physiques and attitudes, India has now left the rest far, far behind in timings, distances, points.

This, even when the armed forces no longer contribute the kind of talent to track and field and contact sports that they did in the past.

I know senior armed forces commanders get irritated at the mention of the 'G' word. But the fact is a golfing culture is now subsuming their traditional love for tough physical sport.

The size of a population has nothing to do with sporting excellence.

It is also a matter of culture, tradition and role models.

Haryana, with less than two per cent of India's population wins nearly two-thirds of its Olympic sports medals and tiny, impoverished Manipur, with no more than three million people, and a terminally broken politics and governance, excels at world level in sports as diverse as hockey, boxing, women's weightlifting and archery.

Kerala has been a traditional powerhouse too. But Gujarat, with three times Haryana's, almost double of Kerala's population, and 20 times Manipur's, is struggling to produce a qualifier.

With a hundred-plus in the world top-25 and rising, we are making progress.

The last Asiad showed stunning improvement with 57 medals, including 11 gold.

The next target should be a clear number fourth Asiad spot, ahead of North Korea, Thailand, Kazakhstan and Iran.

That will be more realistic, yet ambitious.