It is almost midnight and our visitor from Delhi after his 36 hour travel to Brasilia is fast asleep. I am still watching a late night mystery on television. Suddenly there are deafening cracker sounds all around us and the sky is lit with fireworks.

It is almost midnight and our visitor from Delhi after his 36 hour travel to Brasilia is fast asleep. I am still watching a late night mystery on television. Suddenly there are deafening cracker sounds all around us and the sky is lit with fireworks.

My friend gets up in a panic. "Is it a Brazilian Diwali or an insurrection?" he asks. He is a witty man.

"Neither. They have just won a football match, somewhere," I answer, no stranger to this phenomenon.

"Football match? I thought that the World Cup is next year."

"Yes, but every week is a contest here," I say truthfully.

Actually, twice every week or is it thrice? The world is a ball and the ball is the world in Brazil, as I have discovered.

Mention the world Brazil and the first association in anyone's mind is that of football. Samba and carnival come next. Is football to Brazil, what is cricket to India? No. It is much more. But there are valid comparisons.

Football was brought to Brazil by the British, the way cricket came to India. How do we know? This is well documented and Charles Miller, son of a British expatriate railway man is credited as having brought the first football and the rulebook in 1892.

The first big match in this European import was played in Sao Paulo in 1914, and it took another four decades for Brazil to win the World Cup in Sweden in 1958 for the first time.

Between the eminent sociologist Ashis Nandy and historian Ramachandra Guha, we now have the brilliant thesis that cricket is an Indian game invented in England. They have shown how it reflects the Indian temperament, of how it is a game essentially of individual character and chance, though skill and talent may be important.

Witness the lonely hero, say Sachin of yesteryears, going into battle with the hopes of his whole nation resting on his shoulders: he can score a century or get out on the first ball. He is a genius and virtuous and, all that, but his destiny, vidhi, too plays a role.

Nandy argues that irrespective of the historical origins of cricket, it is in the Subcontinent that it finds its rightful appreciation: multitudes at leisure enjoying the interplay between the individual, his team, Time and Luck.

Similar analysis has been made between Brazil as the natural habitat for football, a European import, though I suspect that Brasilians are not as fond of theorising as we are. As I said, the first teams were all European and white in the early 1900s, but soon it had become a national passion.

Several reasons are cited. First, the game was a social equaliser; you did not need expensive equipment or even a proper field; even children from the favelas, slums, of which Brazil has many, could joyously kick around a ball on the streets.

Second, football has provided the passport for fame and fortune for many poor Brazilians and has created role models. It is like the dream of the NBA for a tall and talented black American, of the marathon winner for a Kenyan.

Third and more complex, there is a natural athleticism and aesthetic quality to the Brazilian physique, whether black or white, possibly partly due to the intermixing of races over centuries. The spirit of Samba, a form of infectious energy and acrobatics that manifest itself in dance, also shows itself as choreographed movement on the football field.

The cognoscenti in football tell me that there are two styles: European: robust, fast, aggressive and a well-planned collective effort towards the goal. And the South American, above all, Brazilian: relatively slow with bursts of speed, individualistic, innovative and essentially artistic with the means -- the dribbling, the trickery, and the passing, seen as pleasurable as the end -- the Goal. Different people, different footwork.

If well played English football is like a symphonic orchestra, well played Brazilian football is like a hot jazz concert with bursts of individual talent, says an expert.

But there is no doubting their commitment and also their achievements. Brazil has won the World Cup five times, the most successful country so far. Its recent victory in the Confederation Cup in South Africa has created the hope here that they could be the champions in the first ever World Cup in the African continent next year, in the 2010 cup in South Africa.

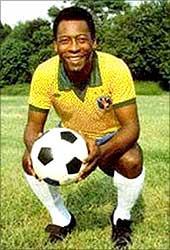

How could have I written so much without mentioning Pele even once? It is like talking about India without mentioning Gandhi. The most iconic Brazilian of all time, Edson Arantes Nascimento, universally known as Pele has a typical Brazilian story. For one, even he does not know where his name came from.

How could have I written so much without mentioning Pele even once? It is like talking about India without mentioning Gandhi. The most iconic Brazilian of all time, Edson Arantes Nascimento, universally known as Pele has a typical Brazilian story. For one, even he does not know where his name came from.

Born in extreme poverty, Pele played in four World Cups, scored his first World Cup goal in 1958, has scored some of the most legendary goals in the history of football and is one of the greatest sportsman of all time. To prevent Pele from being stolen for money by the European teams, Brazil had to declare him an 'official national treasure!'

A story I heard, perhaps a Brazilian urban legend concerns Pele and the great French intellectual Jean Paul Sartre. In the seventies, Sartre was visiting, Rio de Janeiro, where he had many admirers. One lazy morning a group of them followed him as he took a slow walk on the lovely beach, some of them discussing existentialism, no doubt.

From the other side of the beach, came another group following Pele. Both celebrities met and were introduced to each other. Sartre had heard about Pele, but not the other way around, of course. Later the two groups resumed their walk in the opposite directions.

After a few minutes, Sartre turned around to find that most of his 'existentialist' disciples had now decided to follow Pele and he was left with a few stragglers. I am told that this meeting point of the two great maestros, one with his head and the other with his 'headers' is still known as Pele-Sartre corner.

Unlike in Pele's time, today football in Brazil is also a ticket to prosperity through the rich clubs of Europe. It is estimated that there are over 10,000 professionals that the country has produced. Many of their mysterious and romantic sounding names adorn daily reports: Socrates, Robinho, Ronaldinho, Kaka, Zico.

Come the World Cup, many of them return to their national team and speaking for myself I cannot wait to cheer them in 2010, secure in the knowledge that unlike in cricket, there will be no Indian team to claim my patriotic loyalty.

The other day, three of us, diplomats from India, Brazil and South Africa were dreaming up something new for IBSA, the grouping of our countries which is to meet at the summit level in Brazil this year. Sports is obviously an exciting arena. "We will teach you cricket," me and the South African told our Brazilian friend since he said that he cannot understand that mysterious game, virtually unknown in his country.

Brazil and South Africa can teach decent football to India, they said and I did not bring up Mohan Bagan. To complete the IBSA triangle, what can Brazil and India teach to South Africa, we wondered. Any thoughts?

B S Prakash is the Indian Ambassador to Brazil and can be reached at ambassador@indianembassy.org.br

For more of his columns, please click here

Lead image: Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva gifts a Brazil soccer shirt to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The other image: One of the greatest sportsmen this planet has seen: Brazilian soccer legend Pele.