Two-time Pulitzer Prize winner Paul Salopek is on an intercontinental journey of 24,000 miles, tracing humankind's movement out of Africa right down to South America.

Nikita Puri traces his passage through India.

In February 2018, Arati Kumar-Rao waited at India's Wagah-Attari border with Pakistan.

An environmental photographer and writer from Bengaluru, Kumar-Rao was there to welcome Paul Salopek, a journalist who by then had been walking across countries and documenting stories through writings, videos and pictures for five years.

The American is a two-time Pulitzer Prize winner (1998 and 2001) and a National Geographic Fellow whose entry into India was part of a journey that spans 24,000 miles.

He hopes to trace the paths of the first humans who migrated out of Africa 60,000 years ago.

This project, called the 'Out of Eden Walk', will end at Tierra del Fuego in South America, one of the last places to be inhabited by humans.

Salopek's journey began in Ethiopia, at Herto Bouri, one of the world's oldest human fossil sites, in January 2013.

It took him five years to reach the India-Pakistan border, where Kumar-Rao met him.

She is among the nine men and women who became Salopek's walking partners as he traversed India.

Every time Salopek crosses into another country, he writes a 'goodbye letter', an essay commemorating his time in the country he leaves behind.

His last dispatch from India is now online but differs from the previous essays -- this time it is Salopek's walking partners who share their stories.

These, alongside Salopek's own documentations, sprawl across the fields and rivers of Punjab, Rajasthan's Thar Desert and the hills of Madhya Pradesh to Uttar Pradesh's holy cities.

Stories from Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya and Manipur also feature.

For Salopek and his fellow travellers, shelter was sometimes the shade of a tree, or a granary.

They'd walk between 15 and 27 miles a day.

A break could mean sleeping on plastic chairs, waking up to find their t-shirts drenched with sweat.

Salopek's route out of Africa was planned taking into account archaeological records and advances in human genetics.

The day-to-day diversions and stops are not.

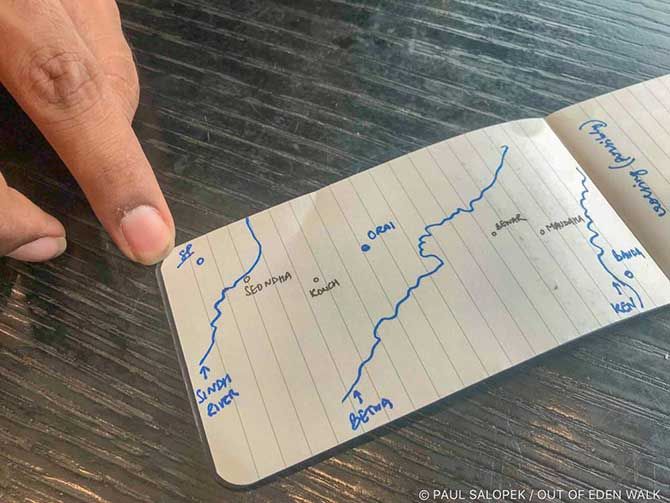

"In the short term the anchors for our routes were more for the stories we could find, and not really the cities and the towns," says Siddharth Agarwal, a Kolkata-based aerospace engineer who has been documenting India's rivers as the founder of a non-profit called Veditum. He was one of Salopek's walking partners.

Dependence on Google Maps meant unexpected adventures.

When Bengaluru-based journalist Prem Panicker, another partner, sprained his ankle, he hitched a ride on a tractor to secure accommodation at a supposedly nearby guest house. (Panicker insists the ankle wasn't bad the first time he hurt it; Salopek insists it was amazing that Panicker walked for miles on desert roads with an ankle that had swollen to the size of a grapefruit.)

There was no guest house. The place was where a local family, the Tandis, would set up rest stops for pilgrims. It was a pilgrimage-season affair only.

That night, the Tandis fed their unexpected visitors in plates so large they had to be carried by two people.

One of the biggest takeaways from the trip, says Panicker, was the kindness of strangers and the camaraderie between the walkers.

Another, says Kumar-Rao, is the knowledge that all her needs can be packed into a bag: A case for minimalist, sustainable living.

Among the countless stories is the time when Kumar-Rao ventured out to the Beas river while Salopek was unwell.

She asked a boatman if he had seen any Indus river dolphins -- a 2018 WWF-India study indicated there are only five to 11 of them left in India.

"I just saw two," the boatman said.

Kumar-Rao hopped on to his boat and they went up the river in time to spot a mother and a calf.

Salopek dragged himself out of bed to see the dolphins.

The mother and calf finally rewarded him on his third attempt.

Salopek stumbled into journalism by accident.

He was headed to a job in the Gulf of Mexico, on a prawn fishing boat, when his bike broke down.

Salopek picked up a reporting job in 1985 at a local newspaper only to earn money to fix the bike.

Stories are all that Salopek carries with him.

"I can't carry much weight, so I don't collect souvenirs," he says.

He accepts some gifts for their emotional significance, such as a keffiyeh headdress given by a walking partner in Saudi Arabia, slippers knitted by a host in Kurdistan, and a traditional Uzbek shirt.

He ships these home to the United States.

"Paul wanted his walking partners to share their biases with him. He wanted to see India from our lens too," says Agarwal.

This wouldn't be the first time Salopek has tried different perspectives.

Salopek, who has a pilot's licence, has also worked as a labourer in a gold mine and on fruit farms, managed a cattle ranch, installed walk-in freezers, worked as a landscape labourer, and refuelled aircrafts at airports.

A coalition of perspectives shapes Salopek's writings which touch a multitude of subjects, from sand mining in Bihar to the songs of the cicadas in the Jaintia Hills. (These songs were so loud that Salopek says it was as if all the world's cicadas had converged there, a 'global conclave of cicada-dom'.)

"I was a rebel. I fought injustice," says former dacoit Malkhan Singh, 76, who lives in Gwalior. He sleeps with a rifle "for my protection".'

He writes of meeting a former dacoit in Gwalior (who still sleeps with his rifle), and a pizza-maker from Bihar for whom the US-Afghanistan conflict meant good business.

He writes of how farmers in Manipur find relics from the Battle of Imphal.

In between deep dives on subjects as serious as climate change, Salopek's humour shines through.

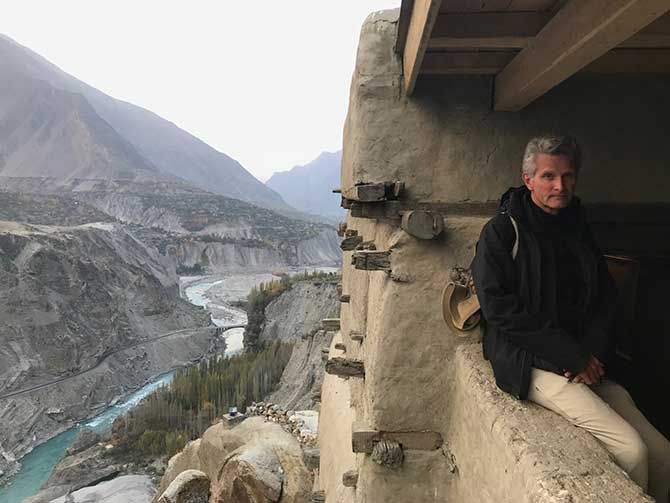

One of the great dangers in the world is the 'homicidal motorised traffic' of northern Pakistan, he writes.

The 'Out of Eden Walk' was originally meant to take seven years -- this could have been the year that marked the end of the walk.

Instead, Salopek, who crossed into Myanmar through the Moreh Tamu crossing in Manipur, is currently in a remote town called Putao in the foothills of the Himalayas.

Halted by COVID-19, he's researching the route ahead.

His commitment to the walk, of slowly discovering the world, has only deepened, says Salopek.

"I never knew, leaving Africa, how far I would get. I can say now that I was measuring things all wrong -- stupidly -- by distance, by time," he says.

"Measured properly, by the quotient of joy this journey deposits in my heart every morning when I wake up, I can report that this journey is just beginning: it starts freshly again and again, every single day."

Salopek doesn't always have guides or walking partners.

His lean frame walking across countries might cut a solitary figure, but there's a world of readers that keeps step with him.

National Geographic Fellow Paul Salopek can be followed in real time on outofedenwalk.org

Production: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com