On August 5, 1953, Jawaharlal Nehru sent a strange note to the foreign secretary. It is worth mentioning because it was symptomatic of the lack of knowledge about Western Tibet in India and in South Block in particular, notes Claude Arpi.

It was recently announced that during the last three years, the state of Uttarakhand has reached 'a significant achievement'; it was visited by over 23 crore (230 million) tourists and pilgrims: 'This surge in visitor numbers has directly supported the livelihoods of numerous stakeholders, including operators of homestays, hotels, eateries (dhabas), womens' self-help groups, and transport businesses throughout the region.'

Reading this, I wondered how many among those 230 million visitors were aware of the old trade and cultural linkages between most of Uttarakhand's border villages, particularly in the districts of Uttarkashi, Chamoli and Pithoragarh and Western Tibet (also known as Ngari).

For centuries, these villages have been at the centre of extensive trade relations with Tibet.

Already not well known in the 1950s

On August 5, 1953, Jawaharlal Nehru sent a strange note to the foreign secretary. It is worth mentioning because it was symptomatic of the lack of knowledge about Western Tibet in India and in South Block in particular.

The prime minister noted: 'Do you know anything about the report mentioned in this telegram about Lakshman Singh or his so-called Indian Trade Mission? What is this 'News Weekly' and how has Lakshman Singh and party gone to Tibet? There is some reference in this telegram to Western Tibet.

'Western Tibet is normally approachable from Ladakh. It is rather odd for anyone to enter Tibet from Ladakh.'

The prime minister did not know that India had a trade mission in Ngari, with the main trade center in Gartok.

Lakshman Singh Jangpangi, a native of Uttarakhand, was the Indian Trade Agent (ITA) in Gartok.

An article of B D Kashniyal published in The Tribune on September 18, 2009, talked about 'Villagers at the India-China border who could have detected enemy movement are moving out due to lack of employment'; it paid a tribute to Lakshman Singh Jangpangi 'from Johar Munsiyari who in 1952 informed the government of India about the Chinese build-up in the area.

'The Union government realised the importance of this information in 1959 when China occupied the whole of Tibet.'

On January 8, 1959, Jangpangi was awarded the Padma Shri for having informed Delhi about China's presence in the Aksai Chin region.

The Gartok Agency was a seasonal one; every year during the summer months, the Indian Trade Agent would tour the high plateau north of Uttar Pradesh (today's Uttarakhand), Himachal and east of Ladakh.

The Indian Trade Agent's role was vital to regulate the flourishing trade between India and Tibet.

Like his colleagues in Gyantse and Yatung, Jangpangi's services were attached to the ministry of external affairs and he worked directly under the Political Officer in Sikkim.

The border villages in Chamoli district

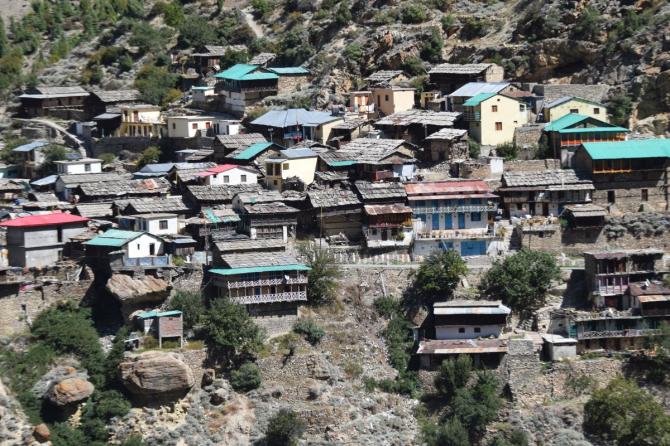

I recently had the opportunity to visit the villages Malari, Bampa, Niti, Gamshali and later Mana in the footsteps of the traders going to Tibet.

Niti and Mana are today known as India's First Villages, as they are the last inhabited places before the India-Tibet border located at Niti-la (pass) and Mana-la respectively.

The Niti Valley, in the northern-most region of Uttarakhand, lies at an altitude of 3,600 metres, 38 km from the pass marking the border.

The Niti Pass has been for centuries an ancient trade route between India and Tibet; unfortunately, it was closed after the 1962 War and never reopened.

Niti and the nearby villages of Malari, Bampa and Gamshali are mostly inhabited by people of the Bhotiya tribe, though they call themselves 'Rongpa' (Rong means valley, 'people of the valley').

Their language is a mix of Tibetan and Garhwali.

These villages are only inhabitable during six to eight months; in winter, the villagers migrate to lower regions.

I had the good luck to meet 82-year-old Bacchan Singh Negi, a retired postman living with his friendly wife in Niti village.

He had been to Tibet when he was 18 years old and still remembers clearly the pre-1962 times.

He explained that Niti and the nearby villages used to trade with Daba Dzong (district) in Tibet and were in contact with the Tholing monastery (he called it 'math').

It was a fascinating journey for all able men of these villages to trek to and trade their goods in Tibetan marts on the freezing and windy high plateau.

Negi even remembered that his family would get ghur (jaggery) from Calcutta to resell it Tibet.

Salt (a crucial valuable commodity), wool, including fine pashmina for shawls, yak tails, borax and different handicrafts were also bartered.

During an interaction in a public school in Gamshali with a group of villagers of Malari and villages on the way to Niti village, I heard fascinating information on the villagers' ancient way of subsistence, which no longer exists.

When asked what they aspire for, most of the villagers immediately said they want better communication, improved health care and education for their children.

This is a recurring demand was for education, the children still need to go to larger towns (Joshimath or Dehradun for further study).

Though the roads have greatly improved in recent years, due to the harsh terrain (and the particularly bad monsoon this year), travelling in these areas remains a challenge, especially with the afflux of lakhs of tourists ...and the resultant traffic jams.

Referring to the central government scheme, known as the Vibrant Village Programme, one lady pointed out that these remote villages are not yet really 'vibrant', though the civil administration and the Indian Army are trying their best to facilitate their lives: "Why can't Mr Modi reopen the passes to Tibet?" she forcefully pleaded.

Indeed, the lives of the villagers changed completely after the closure of the India-Tibet border in 1962 as nobody can visit the villages, marts or religious sites on the northern side of the international boundary.

Of course, tourism (particularly with homestays) is a new source of revenue, but people like the old postman still speak with nostalgia of the ancient times when they could spend the summer months in Tibet; there the Indian Trade Agent's presence was a real boon for their survival on the plateau.

The linkages with Western Tibet were so deep that some villagers in Bampa had properties in Tibet.

I was given the name of a person who still had land pattas for his properties near Gartok. Though I was unable to meet this person, such important documents would prove the close ties between the Indian Himalaya and Ngari.

It could be displayed if one day the government decides to build a museum for India-Tibet border trade in Niti or Mana.

Mana Village

Mana village, also located in Chamoli district, is perched at an altitude of 3,200 metres.

Mana is the last Indian inhabited place before Mana-la (pass) some 50 kilometres away on the India-Tibet border.

The village lies at a distance of 5 km from Badrinath which is visited by millions of pilgrims and yatris every year.

As per Census 2011, the village has a population of about 1214 souls, belonging to the Marchha and Jad clans.

Like in Niti area, the entire population migrates to lower designated villages in winter.

In Mana village, Pitamber Singh, a former Pradhan who spoke good English, knows very well the history of the area.

His father used to go every year to Tibet; Mana village was trading directly with Gartok, not Daba like the Niti area villagers.

Like in Bamba, some villagers had properties in Tibet, some even built houses in Gartok, the main center of Western Tibet.

The wood for the Indian Trade Agency (which was to be built in the mid-1950s in Gartok by the Indian government), was to come from Mana.

Unfortunately, due to the constant Chinese obstructions it was never built. But this incident shows the extent of trade taking place over the pass.

Pitamber knew well Lakshman Singh Jangpandi, the Indian Trade Agent in Gartok for several years and he is still in contact with his son who lives in Almora.

The Uttarakhandi traders were indeed like one family, though each village was assigned a separate trade mart in the Ngari region of Tibet.

A Museum of Indo-Tibet Trade

It would be important to have a modern, well-designed museum in Mana in view of the thousands of pilgrims who visit Badrinath, located a few kilometres away.

It would showcase India-Tibet relations pre-1962 -- the border trade, the cultural exchanges or the life in the border villages.

It has been done successfully in Munsyari in Pithoragarh district by the late Dr Pangtey (also in places like Tawang, the beautiful Major Bob Khathing Museum).

Old dresses, utensils, saddles, photos, documents, paintings, books and films could be displayed/shown.

For the general public (tourists and yatris), it would greatly enhance their pre-1962 knowledge of India-Tibet relations in this area.

It is important that this relationship should not forgotten in the dark wells of history.

Before the day the border is fully reopened, one or several Kailash 'corridors' (on the lines of Kartarpur in Punjab) should be envisaged between India and Tibet.

Tibetans could be allowed to visit Mana or Niti or other places of interest and Indians could enjoy the Tholing Gompa and other sites in Western Tibet (including Kailash and Manasarovar).

Furthermore, India could offer some expertise to the gompas of Tholing. Tsaparang or Piyang to reconstitute the old frescos often destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

This would be an excellent confidence building measure between India and China to start with.

Claude Arpi is Distinguished Fellow, Centre of Excellence for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence, Delhi.

Mr Arpi is a long-time contributor to Rediff and you can read his earlier columns here.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff