Dissonant artistic visions drove Annapurna Devi and her husband Ravi Shankar apart, notes Swapan Kumar Bondyopadhyay.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

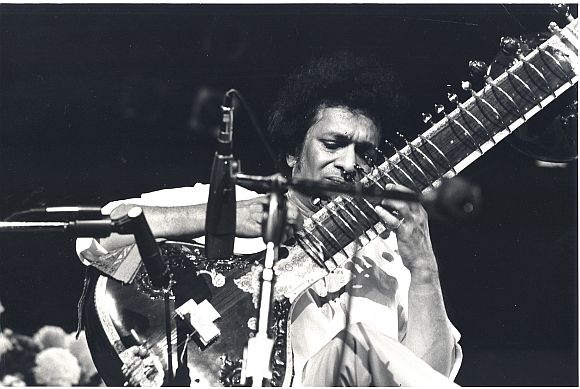

March 30, 1955. The last item of the music conference organised by the Constitution Club of New Delhi was a jugalbandi presentation by Ravi Shankar and Annapurna Shankar.

That day's programme began with Annapurna's recital of Ragashree. Annapurna started the alap in the mandrasaptak. Ravi Shankar occasionally touched a few notes in the madhyasaptak.

After some time Ravi Shankar came down to the mandrasaptak and rested on the kharaj string. The two strings of the chakari and the strings of the taraf created resonance.

After this Ravi Shankar and Annapurna started vistar in the nonpareil mirkhandi fashion.

Annapurna touched on the ati komal rishab or the ati komal dhaibat so carefully that it seemed something uncanny was going to happen.

Ravi Shankar was also depicting the traditional rup of the raga. But despite all this it seemed Annapurna excelled him in ease and naturalness.

There are many myths relating to Annapurna's music. Many say that her father had directed her not to play in public so that Ravi Shankar's playing does not sound lacklustre to the audience. Maybe Baba said all this due to his love for his son-in-law.

Some others say that at the time of his talim under Baba Allauddin Khan Annapurna would help Ravi Shankar in his riyaz.

After that evening's recital there was humming among the audience. Then the judgement of the listeners placed the crown on Annapurna. I do not know if Annapurna ever performed in public after this.

Ravi Shankar and Annapurna were back home after the recital. Annapurna went to the kitchen. Subho (their son) was busy with his pencil and sketchbook. Ravi Shankar came out after a refreshing bath. He was unusually grave.

As they sat for dinner Ravi Shankar tried to unburden his heart.

'I am facing some problems adjusting the duet programmes...' he said tearing away at the chapati.

'What kind of problems?' Annapurna asked, but her voice lacked inquisitiveness. It seemed she already knew what her husband had in store for her.

'I am trying to put it into your head that things are changing. The wind of change is blowing. We must catch up or we would fall behind.'

'Why do you say so? Why this?'

'This is very simple. We have to bring in some modern touches to our music.'

'I do not follow...'

'Not that you do not follow. You deliberately refuse to follow. From the very first day of our marriage, I have seen that you have not tried to modify or change yourself.'

'For example?' Annapurna chipped in with a touch of sarcasm.

'I wanted you to dress up for the occasion. You just threw away the sarees and left aside the ornaments. How very odd.'

'This talk has been going on forever. I thought we've had enough of this. Why do you unnecessarily raise it again? Don't you remember what I said when you complained of my showing scant regard for your suggestion? I had told you that I shall listen to what you say, wear colourful sarees and flashy ornaments, but then in that case you will have to change yourself too. You have to be faithful to me.'

'It was not possible for you to keep your word. I made all kinds of adjustments and now you are throwing all these accusations at me. Before you call me a ziddi just search your heart. But let that go. I wonder why you are saying all these things here today?'

Ravi Shankar was accustomed to the sternness in the voice and the attitude. He said whatever he had to say.

'I know it’s all useless,' he said, 'You have never seen nor will see reason. You are orthodox. Opinionated like a school mistress, a spinster, glossing over all the good things of life.'

Such words gave him a little relief and he carried on: 'Listen, Anu, we cannot play like this. In fact the artists should create the prevailing taste for the audience. As in literature the poet or the novelist strives to change the taste of the reading public by introducing a new style and new idiom. If we always cling to the old, that will not do.'

'The times are changing. We are not in the age of the maharajahs when life was slow and idle. Life now is fast and complicated. So the days for your elongated vilambit meends are out. You may get applause and appreciation now, but...'

'I am playing whatever I have learnt from Baba. He taught us the dhrupad-ang alap. I dwell on each swara for a long time and love to play alap. I do not know what the changing times will require.'

'But...' Ravi Shankar tried to intervene.

'I want to play Baba's music whatever happens. All my life I shall play that. I won't budge an inch,' Annapurna said.

'I know. I know. You can bring in some feeling into your music. You stick to a note and squeeze out every ounce of sur from it. Everyone raves about it. That is the beauty of the surbahar. The sitar suffers from an inferiority complex. But still I feel it is no use sticking to the old world. One should move with the times. I have decided to call it off.'

Annapurna knew it would be futile arguing with him. Ravi Shankar was a person with a marvellous sense of timing. So whatever he would decide would be best for him. Only she might not agree with him.

She looked fixedly at Ravi Shankar so that he would not stop and elaborate on whatever he was thinking inside.

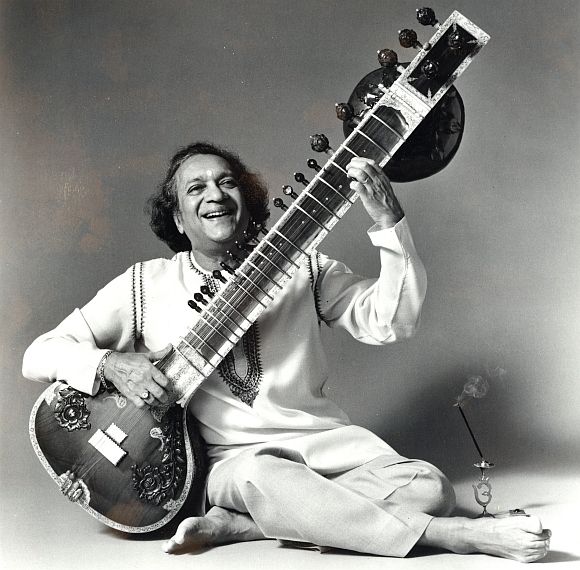

'This is the age of the sitar. So I prefer the sitar and not the surbahar. Like this is the age of the khayal and not the dhrupad. Dhrupad may be very rich, but the modern man just cannot afford to patronise the slow movement of the dhrupad.'

Annapurna did not feel like replying to Ravi's argument. She felt Ravi was suffering from an inferiority complex because she got rave reviews. The jugalbandis, in their five or six concerts together, were enough to establish her superiority over Ravi Shankar as a performer and musician.

That time Ravi did not know that she would willingly withdraw herself from the public eye. She was on the rise. The connoisseurs hailed her as great. The surbahar also helped to establish her supremacy, because it is a more difficult instrument than the sitar, heavier and more satisfying musically.

Ravi was justifiably jealous. And so he elicited a vow from his wife that she would no longer play in public. There are many versions of this anecdote afloat, mostly apocryphal.

Annapurna, however, told me that something worse had happened than Ravi attempting to make her take this oath. But she added that she would divulge it to none.

'That will go with me when I go,' she said emphatically.

This was bound to happen if the husband and wife shared the same profession. It is the male ego.

For Ravi Shankar it was worse. He was ambitious and egocentric; he would not allow anyone to rule his world.

Truly he was the sun and loved to shine alone in the sky. So perhaps he had decided to take her away from public performances.

Excerpted with permission from An Unheard Melody by Swapan Kumar Bondyopadhyay.