Nearly two million people die from mosquito-borne diseases every year.

What are we doing about it?

What ails India's public health policies?

Here’s a quiz: What’s killed more human beings than any other disease, famine or world war?

You won’t be surprised by the answer: A mosquito bite.

Despite the advances in modern medicine, the undeniable fact is that we’re still unable to combat the deadly effects of a bite from a tiny mosquito. It continues to act as a vector for serious diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, zika, and of course, Japanese encephalitis that is ravaging eastern Uttar Pradesh. Nearly two million people die from mosquito-borne diseases every year worldwide. And the morbidity levels are considerably higher.

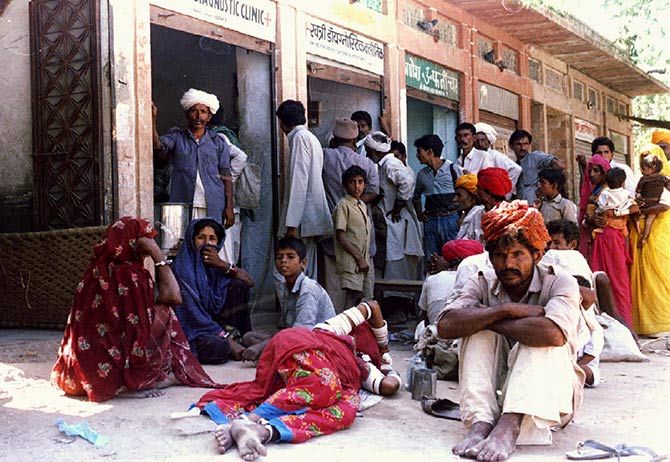

Over the past few days, while the unfolding tragedy in Gorakhpur has once again placed the scanner on the abysmal quality of public health in the country, it has also reminded us that we still haven’t learnt how to deal -- let alone eradicate -- vector-borne diseases.

Is it simply our collective unwillingness to accept responsibility? Or is it just that vector-borne diseases are usually complex problems to combat?

Perhaps, a bit of both.

Take, for instance, malaria. In 1902, Ronald Ross won the Nobel Prize for Medicine for discovering that mosquitos caused the transmission of malaria, largely based on his work in India.

Yet, why is that more than a century later, we’re still figuring out how to eradicate malaria from this country.

The government has set a target to eradicate malaria by 2030. But no one quite believes its official data on malarial deaths, which is pegged at less than 500. Public health experts believe it is in excess of at least 100,000 a year.

Now, here’s another intriguing piece of data. While we may have thrashed the Sri Lankans in the recent Test series, there’s one area where we might have a thing or two to learn from them: Malaria eradication.

In September last year, the World Health Organization gave Sri Lanka a malaria-free certificate for not reporting a single case of malaria for three preceding years. With a population of over 22 million, Sri Lanka might seem puny, compared to India’s 1.2-billion population. But given its long standing civil war in the North, dense forests, tropical climate and a large rural population, there are very few middle-income countries in the world that have been able to eradicate malaria as quickly as Sri Lanka has done.

In the public health space, Sri Lanka is seen as a shining example of how political commitment, sensible yet unconventional strategies, and determined execution can help eradicate the scourge of malaria.

So what’s hobbled India’s fight? Based on my conversations with public health experts, I discovered some key challenges.

One, the phenomenon of growing drug resistance, stemming particularly from the Mekong region and later spreading to the eastern and north-eastern parts of India and now gradually to our western states.

Two, nearly half the malarial deaths are in hilly, tribal regions. And the lack of access to proper health and education systems -- and a worrying reliance on traditional cures -- makes them even more susceptible.

Three, the surveillance system at the primary health care level is broken and that makes it more difficult to detect and report cases in time and prevent epidemics.

Four, in the 'sixties, India was on the verge of eliminating malaria. And that’s when complacency crept in. Political commitment reduced. Funding was yanked off, and India had to scramble to ward off an epidemic in the seventies.

Five, in as many as 30 per cent of malaria patients, the typical symptoms of fever do not manifest and tend to get suppressed. And since these folks are able to go about their normal life, transmission is often difficult to control.

Now, despite ongoing research, there are no vaccines that are likely to fight the malaria virus in the near future. Genomics may well throw up new solutions.

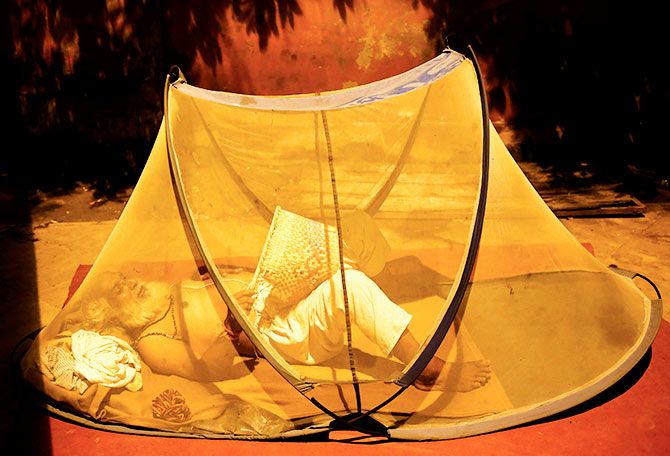

But community engagement is key. And increasingly, the instruments of control are being put in the hands of the community. And that means ensuring the widespread use of insecticide treated bed nets and spraying non-toxic insecticides. Also, the adoption of new hand-held devices among local public health workers will make it easier to quickly transmit data on possible epidemics from remote areas.

India could also take a leaf out of the experiments to breed the wolbachia male mosquitos that help nullify the parasite carrying female mosquitos after mating.

Yet strategies are only as good as its execution. And that’s where India lags behind Sri Lanka.

Our public health system is largely unreliable when it comes to detection and surveillance. Researchers have found that data on malarial deaths doesn’t get captured because they happen at home and largely go undetected. And even if it does get detected, there is a worrying tendency to suppress the data and not, swiftly and publicly, disclose the outbreak of diseases such as zika.

As the Gorakhpur tragedy revealed, passing the buck -- and refusing to be accountable for results -- remain unfortunate national traits. Here’s the moot point: Do we have the collective will to change this depressing narrative?

Indrajit Gupta is co-founder at Founding Fuel, a media and learning platform aimed at serving entrepreneurial leaders.