Archana Masih recalls that December evening 22 years ago when Atal Bihari Vajpayee logged into the Rediff Chat.

It was Christmas Eve, on the eve of Atal Bihari Vajpayee's 72nd birthday.

He had been prime minister for 13 days a few months earlier and had agreed to appear on the Rediff Chat that evening in 1996.

A bunch of us who travelled from Mumbai were frisked by the Special Protection Group at the entrance of his home in New Delhi and were shown into a room where the chat was to take place.

His aides Shakti Sinha and Kanchan Gupta chatted with us about the modalities of Vajpayeeji's first Internet chat experience as we were served tea and snacks on a cold winter evening.

Vajpayeeji's foster granddaughter Niharika, a little girl at that time, could be seen playing around, calling the security staff "SPG uncle" while her mother Namita Bhattacharya told us we had been spelling Vajpayeeji's name wrong all along.

"It is Bihari with an 'i', not an 'e'!" Namita said.

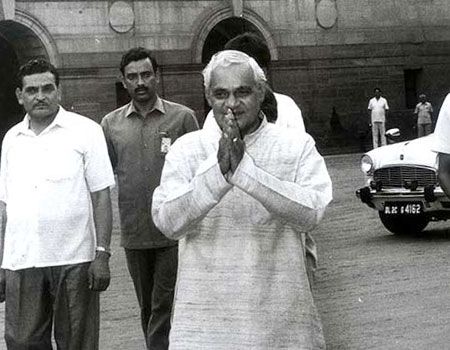

As Vajpayeeji entered the room, all of us instantly stood up. Even though he was a diffident, mild mannered, man, there was an electricity about his presence that inspired awe and respect.

As Vajpayeeji entered the room, all of us instantly stood up. Even though he was a diffident, mild mannered, man, there was an electricity about his presence that inspired awe and respect.

As the questions from Rediff readers were read out, he would often keep his eyes closed while listening to them, then Kanchan or a couple of us would key in Vajpayeeji's answers.

As the questions from Rediff readers were read out, he would often keep his eyes closed while listening to them, then Kanchan or a couple of us would key in Vajpayeeji's answers.

As a couple of my colleagues kept going in and out of the room to check with the Rediff HQ in Mumbai how the chat was doing, Vajpayeeji asked, "Kya aap log cigarette peene baar baar bahar ja rahe hai?" which the duo sheepishly denied like errant schoolboys.

As the last answer was keyed in, we wished Vajpayeeji a very happy birthday to which he said "Dhanyavad!" with typical grace and flourish.

And then he left, as if he was almost in a rush to get away from this new fangled technological gibberish.

The abiding image of that evening was Vajpayeeji, his back towards us as he walked towards the door of his private residence, as he pushed it open, his silhouette against the night light as he vanished inside.

The abiding image of that evening was Vajpayeeji, his back towards us as he walked towards the door of his private residence, as he pushed it open, his silhouette against the night light as he vanished inside.

One of the interesting stories about Vajpayeeji was narrated by the editor just before the 1998 general election which brought the BJP to power a second time.

My photographer colleague Jewella C Miranda and I were about to set course from Mumbai by train and bus travelling through Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh for a month covering the election campaign to reach New Delhi by counting day.

It was going to be our first extended reporting assignment long before the days of wi-fi, personal mobile phones and ATMs.

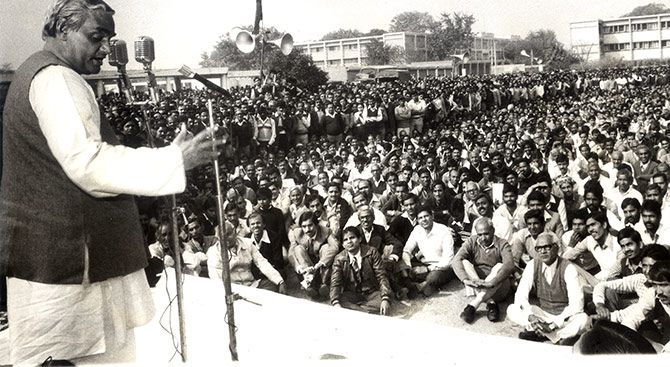

Recounting Vajpayeeji's masterly oratorical skills, the editor recalled one of the then BJP president's public meetings in the mid-1980s.

After accepting the many garlands as his welcome, he took to the mike and told his audience: 'Main haar nahi, jeet lene aaya hoon.'

Punning on the word haar which can mean both garlands and defeat in Hindi, Vajpayeeji had declared, 'I have not come to receive defeat, I have come to welcome victory.'

Vajpayeeji brought a poet's passion to everything he said, sprinkling his speeches with everyday phrases.

Otherwise puzzlingly quiet, he really came alive at election rallies and inside Parliament.

At an election rally near the Itarsi railway station in MP, we would report on one of his election meetings.

Referring to his party's inability to draw support from other parties which resulted in the fall of his government in 1996, Vajpyaeeji told the audience with a chuckle that the BJP's attempt had failed because every other party had not only closed its doors but even windows and ventilators on the party.

The crowds loved it.

His Hindi was simple and listening to it was always a pleasure. Barring the current prime minister, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj and to some extent Home Minister Rajnath Singh, there are not many good Hindi speakers in Parliament.

In fact, really masterful debates in Parliament of the kind we witnessed in Vajpayeeji's hey day in any language are rare now.

A couple of months ago, Punya Prasun Bajpai, before he exited the ABP news television channel, screened a clip on his show Masterstroke of a parliamentary debate where Vajpayeeji was constantly being interrupted by Opposition MPs.

What happened next would be unthinkable today.

'Hush!' Chandra Shekharji, the former prime minister who was seated on the Opposition benches, stood up and declared, 'Let us hear Atalji speak!'

A school teacher's son, Vajpayeeji was a politician, but a sensitive one. His ensitivity was the core to his politics in many ways that shaped his emergence as a beloved statesman.

It was what made him reach out to the Kashmiris, extend a hand of friendship to Pakistan and take a bus to Lahore.

It is what made him counsel a chief minister of a rioting state to follow his raj dharma.

It is what also united the country as her soldiers won back the Kargil heights.

Perhaps, that sensitivity came from carrying a poet's heart, from a love for literature.

If there is a lesson today's politicians can learn from Vajpayeeji whose death brought friends and foes from within the country and without to pay their respects -- it is sensitivity.

After all, it is never too late to reach out for a book and learn how to navigate life -- personal or political.