I telephoned Chief Minister Darbara Singh and asked him why this carefully thought-out plan had suddenly been aborted.

The Chief Minister sounded very agitated and all he said was that this was not his decision, but the orders had come directly from Home Minister Zail Singh.

A fascinating excerpt from retired IAS officer Ravi Sawhney's book, Living A Life.

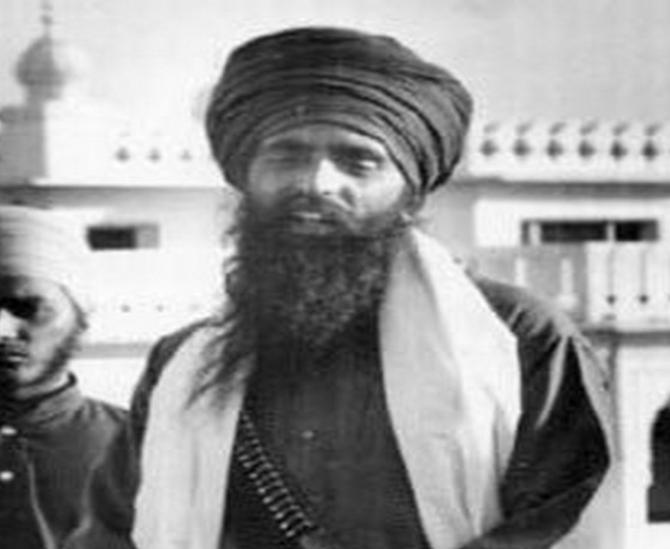

The murder of Lala Jagat Narain was alleged to have been carried out as per Bhindranwale's orders and the police was looking to arrest him on various allegations of violence.

Bhindranwale offered to court arrest in Chowk Mehta, near Amritsar, if he was allowed to address a public gathering.

It became a massive media event for the top leadership of the Akali Dal and thousands of Bhindranwale's followers gathered to hear his speech claiming innocence and to witness his surrender.

Following his surrender, as apprehended, there was large-scale violence in different parts of Punjab.

Hence, the government's decision to send him to Ludhiana for detention was a serious challenge to the district administration.

He was transported from Chowk Mehta under strict security in a convoy of cars.

It was considered imprudent to bring Bhindranwale into the city or to detain him in the district jail which was located in the heart of the city.

We, therefore, planned with the government's approval, to surreptitiously separate his car from the convoy of police escort vehicles well before the convoy entered the city limits and divert it to an undisclosed government rest house in a secluded place.

The welcome arches put up in the city and the large number of people gathered along the road to cheer him vindicated our plans.

However, just about 30 minutes before the expected arrival of the convoy at the spot from where we were to divert his car, SSP Bhatti came to me to convey a message from the Director General of Police that Bhindranwale's car should be allowed to go through the city. He could not explain why this obviously senseless change was made.

I immediately telephoned Chief Minister Darbara Singh, who was in Chandigarh, and asked him why this carefully thought-out plan had suddenly been aborted.

The Chief Minister sounded very agitated and all he said was that this was not his decision, but the orders had come directly from Home Minister Zail Singh.

Following these orders, Bhindranwale's convoy was taken through the city including Bhindranwale's car.

As apprehended, there was a public procession following the convoy which became progressively larger as it went through the city with people in different modes of transport joining it and shouting pro-Bhindranwale slogans.

When we reached the designated place of his detention, there was no secrecy left.

Escorting Bhindranwale from Chowk Mehta to Ludhiana was a senior IPS officer, Chahal, Senior Superintendent of Police, Gurdaspur district.

He had come with a set of instructions regarding the treatment to be meted out to Bhindranwale while in detention.

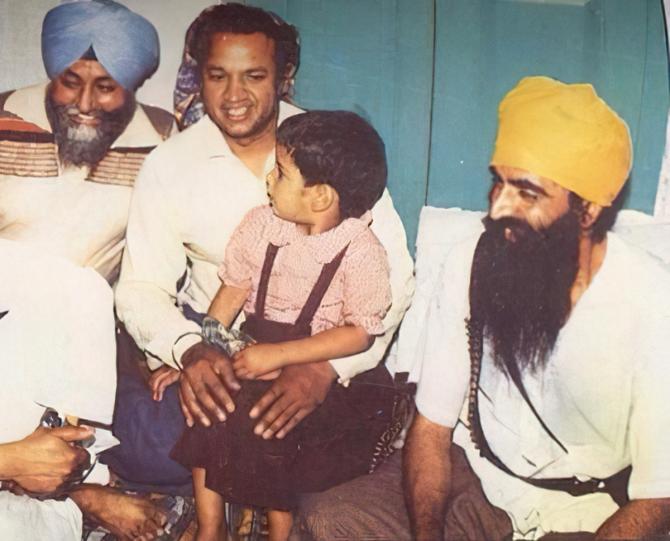

Bhindranwale was still sitting in the Ambassador car with two companions when Chahal came across to where the Deputy Inspector General, Police, Patiala Range, SSP Bhatti and I were discussing security arrangements to convey the instructions which, he said, were agreed conditions attached to his surrender.

- Two companions his cook and his sewak would stay with him

- When he is interrogated, it must be only by a gursikh (a Sikh who observes all five tenets of Sikhism)

- When he is interrogated, he should be sitting at the same level or higher but not lower than the interrogator and

- If he chooses not to answer any question, no third degree method should be used.

I listened aghast and quipped to Chahal, 'Who is under arrest, Bhindranwale or the Punjab government?'

I then turned to Bhatti and said that as far as I was concerned, Bhindranwale was someone under arrest and should accordingly be treated as one under detention.

I did not think it necessary to personally confront Bhindranwale that evening at the place of detention or even thereafter.

I deputed Ludhiana Sub Divisional Magistrate, Hardial Singh, a seasoned Provincial Civil Service officer who was on his final posting before retirement, to visit the rest house daily and give me a report on the security situation there.

The rest house had virtually become a place of pilgrimage with scores of people visiting it every day to see the place where Bhindranwale had been detained.

In fact, the road leading to the rest house was soon lined with food and refreshment vendors serving the visiting public.

After about a week or so, it came to my attention that each time Hardial Singh went to meet Bhindranwale, as part of his daily visit, he would pay his respects by touching Bhindranwale's knees.

So the next time Hardial Singh came to me with his report, I asked him to give me a minute-to-minute account of his visit and when he omitted to say anything on his mode of greeting, I confronted him with a direct question on how he greeted Bhindranwale.

He was still evasive, so I asked him a more direct question whether he greeted him by touching his knees, a traditional mode of greeting to express respect.

With folded hands, Hardial Singh admitted that out of respect for 'Santji', he did bow before him and touched his knees.

I admonished him reminding him that as he was representing me, his action was tantamount to my touching Bhindranwale's knees, and as I represented the government, that in turn meant the government was paying respects to a person under detention on a murder charge.

The situation had become untenable and relocating Bhindranwale became imperative.

I telephoned the Sub Divisional Magistrate of Samrala, Rakesh Singh, a young IAS officer who was on his first posting, and told him that I was transferring Bhindranwale to his charge with confidence that he would treat him as was his due as a detainee.

Bhindranwale was accordingly shifted and detained in a rest house in Samrala subdivision but, as secrecy around his place of detention had already been compromised, the crowds followed him there too.

I then wrote to the government that it was becoming increasingly difficult in terms of security to keep Bhindranwale in detention in the rest house and recommended he be sent to a regular jail.

The jail in Ludhiana, located in the heart of the city, was not suitable for this purpose.

Bhindranwale was eventually shifted to the jail in Ferozepur from where he was subsequently set free for want of evidence to prove the murder charge against him.

This edited excerpt from Living A Life by Ravi Sawhney has been used with the kind permission of the publishers, Konark Publishers, New Delhi.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com