Former RA&W chief A S Dulat, who served as Atalji's adviser on Kashmir, gives us an insider's glimpse of a prime minister he has hailed as the 'greatest after Nehru'.

Less than a week after joining the PMO I received a call on the RAX, which is the government's secure phone line for senior officials and ministers.

On the other end was a woman's voice; the call display showed it was coming from the prime minister's residence, at 7 Race Course Road. I was foxed.

"Welcome to the family," she said.

It was Namita Bhattacharya, known by her nickname Gunu, and she was the prime minister's adopted daughter.

"Now that you're here, we're reassured," Gunu continued. "Please look after the two old men. They are your responsibility."

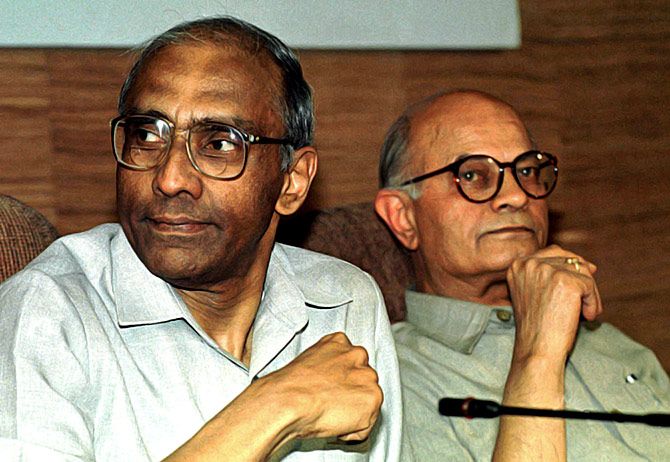

She was not only referring to her 76-year-old father, but also to his 72-year-old principal secretary and national security advisor Brajesh Mishra; but in any case, what she said was not as important as the mere fact of her reaching out to me. I was touched, and thanked her for calling.

The PMO in Vajpayee's time was one big happy family, and had a relaxed atmosphere. Of course, part of it was the kindness that the prime minister showed me in the five-and-a-half years that I was with him -- two in R&AW, and three-and-a-half in the PMO -- but it was also his family who made me feel like one of their own.

In this, Gunu was the anchor as she was the hostess of the house, and she always met me and my wife warmly. The same went for her husband Ranjan: He was an obviously smart fellow who was said to have wielded enormous clout though up close he came across as humble.

Vajpayee would, at least once in six months, invite all the families from the PMO for a meal or a dinner. You would get good food and good drink: It was a supremely relaxed affair.

Behind him on his immediate right is his son-in-law Ranjan Bhattacharya who stayed by his side every night during his final two months in hospital.

When I joined the prime minister's office on the first day of 2001, I asked Brajesh what I was supposed to do. "Anything you like," Brajesh said. "But we want you to focus on Kashmir."

Though the brief was not yet specific I was content because I had spent a lot of time on Kashmir and it was what I enjoyed doing.

A few days later we had a longer chat and I asked, "Okay, what in Kashmir?"

"Elections are coming up next year," the principal secretary said. "We want as much participation as possible, as many people as you can get in."

"Okay," I said.

"And try and get these separatists in," he added.

What more could one ask for? Kashmir had always been my favourite subject and now I would be devoting all my time to it.

What added to these three-and-a-half years being a great experience, possibly the best period in my career, was that one saw everything from close quarters.

There were people who had problems with my brief on Kashmir, be it when I headed R&AW or when I was in the PMO.

Why was I meddling in Kashmir, it was an internal matter? But Brajesh Mishra encouraged it, and even when I was in R&AW he would tell me, every three-four months: "Bhai, woh Kashmir pe PM ko thhoda brief kar dena."

The Intelligence Bureau was not very happy about my meddling, but it carried on throughout my stint in R&AW and the PMO, and only ended when Dr Manmohan Singh came to power and M K Narayanan took over as his national security advisor.

Narayanan made it clear to the R&AW people that they would not meddle in Kashmir. Sadly, a lot of Kashmiris were then dumped by R&AW, and many of them are dissatisfied today.

Those who cribbed about my involvement were technically correct, but the fact of the matter was: they weren't doing anything. So what was the problem with my doing something in Kashmir?

Brajesh needed to stop me if that was the case, and say, look at Pakistan instead. But he encouraged me to handle Kashmir when I was in R&AW and got me to the PMO to specifically deal with it.

I was officer on special duty but unofficially referred to as adviser on Kashmir in the PMO.

Brajesh Mishra in that regard was a great boss. He gave the brief, but how I did it and when I did it, he never interfered. I was free to do things my way.

We had hit it off back when I joined R&AW, and from there it only got better.

Occasionally he might say, "you're overstepping something", or "you're becoming too prominent".

For instance, there was a time I went to Srinagar and a major Delhi paper splashed a story on its front page that I had gone to Kashmir to conduct 'golf diplomacy' with the separatists and other Kashmiris.

Actually, whenever I went to Srinagar during those days I played a lot of golf, and if anyone asked it was a good cover story. Of course I did not go just to play golf, but to meet someone or discreetly take care of some governmental business.

When I returned to Delhi and briefed Brajesh Mishra, he told me that I had become too prominent. "Take it easy for the next three weeks," he said. "I don't want any news."

In our PMO there was no doubt who the boss was -- which has not been the case in some other PMOs. Here, Brajesh virtually ran the government for the prime minister; he was everything.

No wonder he is regarded as one of the most powerful principal secretaries ever to serve a prime minister.

And, of course, he was India's first national security adviser. With so much power he eclipsed even Cabinet ministers.

Everyone who worked in the PMO and who worked with him never complained about Brajesh Mishra. He was good with people, he was clear-headed, quick on the uptake, quick on deciding, he knew how to get things done and he never wasted time.

And yet Brajesh Mishra was an extremely relaxed person, though paradoxically he found it difficult to relax. He loved his drink and smoked a lot, which was bad for him. The doctor stopped him, but he would still smoke three or four cigarettes.

He was not a social namby-pamby drinker. He drank everywhere and he only drank his Scotch.

Also, he would talk about how, when he went to New York, the first thing he wanted to do was go and listen to some jazz. He loved jazz and often spoke of the jazz clubs in New York, which he frequented when he was our permanent representative to the United Nations from 1979 to 1981.

Unlike other bureaucrats, Brajesh Mishra did not like to be seen strutting around. He didn't encourage politicians to come and meet him unless it was the one or two he was comfortable with: Arun Shourie and Arun Jaitley.

He didn't like politicians and he didn't attend political functions, even if the prime minister was going.

Brajesh and Vajpayee had an understanding: You run your politics and I'll run the government. And they got along amazingly.

Which was not the case with the most powerful ministers in the government.

It is strange that the most senior ministers in the government did not see eye to eye with Brajesh Mishra, be it Home Minister (and later Deputy Prime Minister) L K Advani or Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh. And it didn't seem to bother anybody, least of all Vajpayee, who, of course, was an accomplished politician and had a good equation with Jaswant Singh and even with Advani.

On normal days Brajesh Mishra interacted with the prime minister every evening. Vajpayee functioned out of his residence and rarely came to his South Block office, so if any of us had to meet him we had to go to RCR.

In Brajesh's case it was not a question of him briefing the prime minister because they knew each other so well. It was a question of sitting down and discussing a matter.

So at the end of every day Brajesh would leave office at about 6:30 pm -- he didn't sit late, like a lot of people do -- and he would go to RCR, where he would spend his time depending on how much time Vajpayee had. He probably wound up and reached home at 8:30 to 9 pm most evenings.

You might wonder how the government functioned at all in this easygoing manner, but the truth is, in our country the government functions on its own and in Vajpayee's time it functioned smoothly despite the fact that there was a coalition government.

Vajpayee managed the coalition very well: He was good with people, he was good with words, and, above all, he had a sense of humour.

Once, for instance, there was a time when the railway minister, Mamata Banerjee, was sulking. She was a moody person who could be very difficult to get through to.

I witnessed one example of Vajpayee's people skills at the airport. Mamata had stormed out of a Cabinet meeting, and then Vajpayee went on a trip abroad. I was still in R&AW then and in those days we had to go and stand in line at the airport to either see off or receive the prime minister -- more on his return than his departure -- in case he had a brainwave or something and you were required.

At the airport the officials were lined up on one side and the politicians on the other side. For the politicians it was purely optional who went. But on this occasion Mamata was at the airport and she was first in line.

As Vajpayee came in, she bent down to touch his feet, as was her habit. He caught her hand and gave her a hug. That ended all problems with her party, the Trinamool Congress.

Vajpayee could do that.

My only reservation was that Vajpayee took his time in deciding things, particularly in important or crucial matters. You would never be able to tell that from meetings, which he never allowed to meander uselessly; he would sit there, munching his samosa and jalebis, but ensured the meeting was quick and business-like and over.

If he had to say something or make a remark, he would do so; otherwise it was thank you very much.

Nonetheless, Vajpayee was never one to allow himself to be led by the bureaucracy. The bureaucracy anticipates things and tries to be 'his master's voice'.

In Vajpayee's government, however, you never felt an unnatural swing to the right; it was like any other government. Indeed, it was a friendlier government, a happier one, and I don't think the bureaucracy had a better time than during Vajpayee's time.

If you leave it to bureaucrats, things like relations with Pakistan will not improve no matter how much you may personally want to improve them.

When Vajpayee took the bus to Lahore, it was not a bureaucratic decision; it wasn't a whim either, but it was a decision 'driven' by the prime minister himself, with the supporting homework being done by the bureaucracy.

And who would have thought that within two years of Kargil, Vajpayee would invite and talk to General Musharraf.

Excerpted from Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years by A S Dulat, with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.