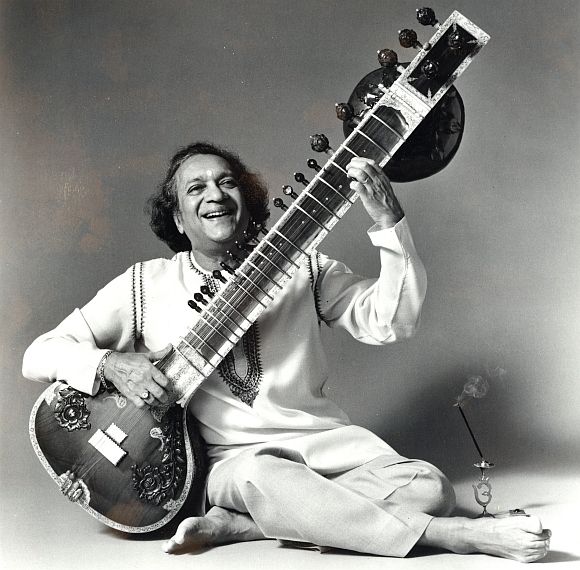

Pandit Ravi Shankar was George Harrison's link into the Vedic world.

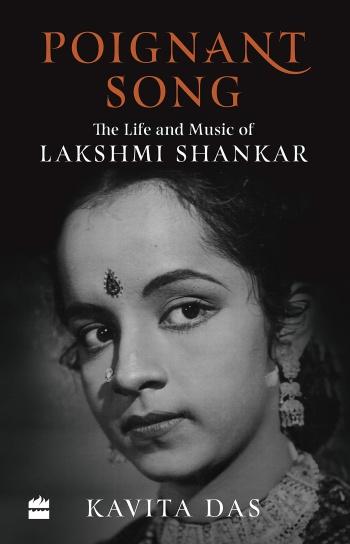

A fascinating excerpt from Kavita Das's Poignant Song: The Life And Music Of Lakshmi Shankar to mark Pandit Ravi Shankar's birth centenary on April 7.

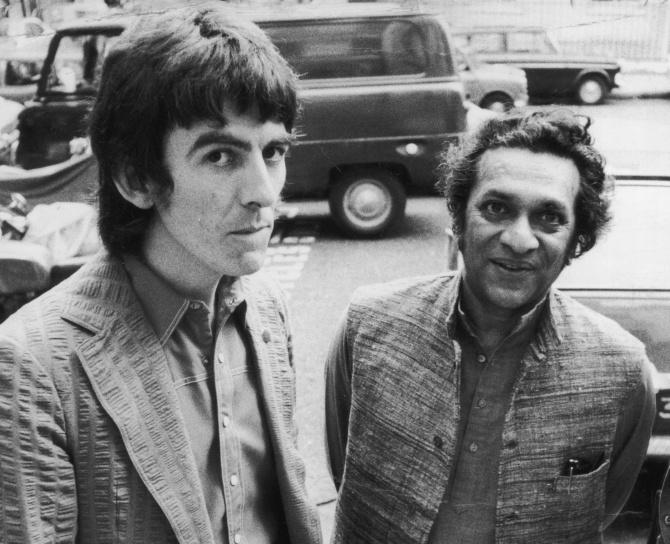

Ultimately, Ravi was convinced by George's earnestness and they commenced lessons. George said of Ravi:

'Ravi was my link into the Vedic world. Ravi plugged me into the whole of reality... The moment we started, the feelings I got were of his patience, compassion and humility. The fact that he could do one of his five-hour concerts, but at the same time he could sit down and teach somebody from scratch the very basics: how to hold the sitar, how to sit in the correct position, how to wear the pick on your finger, how to begin playing.'

The Harrisons and Ravi absconded to Kashmir and took refuge on a houseboat.

In this idyllic setting, George spent several weeks studying sitar intensely with Ravi.

But their time together transcended from sitar lessons to an immersion in Indian culture and spirituality.

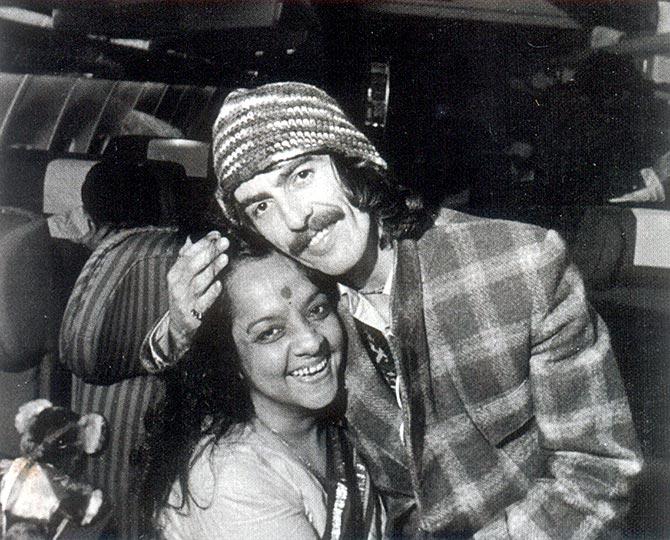

It was during this time that Lakshmi and Rajendra Shankar (Ravi Shankar's brother and sister-in-law) met George and the rest of The Beatles.

George credited both Ravi and Rajendra with supporting him on his spiritual journey by providing him with seminal books like Paramahansa Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi and Swami Vivekananda's Raja Yoga.

Lakshmi was aware of George's status as a rock superstar, and she was struck by both his warmth and his deep affinity for Indian music and culture. 'He must have been an Indian soul.'

At one point George visited Lakshmi and Rajendra at their Bombay apartment for a homecooked meal, but word travelled fast and soon a crowd of people assembled on the street outside the building.

The other members of The Beatles also made an impression on Lakshmi. 'John was a little reserved, Ringo was very free, Paul was a little proud,' Lakshmi said, smiling as she thought back to her first time meeting the Fab Four.

On June 1, 1967, The Beatles released Sgt Pepper's Lonely Heart Club Band. The album features Within You Without You, a song composed and orchestrated by George.

Ravi's influence on that song is evident. The song is defined by the lilting melodiousness of Hindustani music and is filled with Indian instrumentation.

George plays the tanpura, sitar, the acoustic guitar, and sings. In fact, he's the only Beatles member who is featured on the song.

Several Indian musicians accompany him on the tabla, dilruba and swarmandal.

George said of the making of the song:

'Within You Without You came about after I had spent a bit of time in India and fallen under the spell of the country and its music. Within You Without You was a song that I wrote based upon a piece of music of Ravi's that he'd recorded for All India Radio.'

Meanwhile, Ravi was much sought after to play at rock and pop festivals, a major departure from the traditional music venues and forums he'd been participating in till then.

Although he was a bit wary, he viewed it as an opportunity both for Indian music and him to reach new audiences.

In June 1967, Ravi and Alla Rakha were invited to play at the Monterey Pop Music Festival in California, whose line-up included rock and pop greats like Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Janis Joplin, and Simon and Garfunkel.

The following year, Ravi was invited to the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, the legendary weekend-long festival that defined the hippie youth culture and counterculture of that era.

He had a drastically different experience there, finding the crowd rowdy and inattentive, more interested in drugs and 'free love' than in the music.

Ravi was particularly disillusioned by the conflation of Indian culture with drugs and hippies, which he felt disrespected the sanctity of Indian spirituality and music.

'I felt offended and shocked to see India being regarded so superficially and its great culture being exploited.'

'Yoga, tantra, mantra, kundalini, ganja, hashish, Kama Sutra -- they all became part of a cocktail that everyone seemed to be lapping up!'

To make matters worse, Ravi's attempts at bringing Indian music to the West and collaborating with Western musicians were being criticised by some Indian musicians and music critics as tainting and diluting Hindustani music.

Lakshmi was a witness to how Ravi was affected by this criticism and misrepresentation of his ambitions.

'He never tried to change Indian music. There was one time where people started saying, "He's playing guitar, not sitar." You know how people talk,' Lakshmi told me with a shake of her head, casting aside these dubious aspersions.

In his quest to help Western audiences understand and appreciate Hindustani music, while Ravi was unwilling to compromise on the content of the music, he agreed to adjust the presentation of it to make it acceptable to the Western palate.

For example, Hindustani concerts can go on for several hours in India, with each piece lasting for over an hour.

For his concerts in the West, Ravi would shorten the length of the pieces.

Lakshmi also noted how his innovations in concert lighting were sometimes disparaged.

'He even tried lighting in the raga, alaps. If he wanted to play Darbari (an evening raga), he wanted night, so he put dark light, dim light, blue light. And even then they said, all these are gimmicks. Anything new you do, people don't take to it.'

Lakshmi chalked up some of the criticism coming from fellow Indian musicians to envy.

According to Ravi, a few of the musicians who had been critical of him took 'full advantage of the chances which now opened up for them as a result of my success'.

Of Ravi's resilience, Lakshmi said, 'That was so difficult but Raviji was a strong person. He just went on and on, with his own conviction.'

It was certainly a breakthrough time for Indian music; however, there were many instances when musicians simply hopped on to the trend and appropriated it without bothering to truly understand it. This was especially true of several rock 'n' roll bands.

Thankfully, there were exceptions like George Harrison and Mickey Hart, the drummer of The Grateful Dead, who, like George with the sitar, undertook a serious study of the tabla.

Indian music was also spreading through collaborations, like the ones between Ravi and jazz and classical musicians.

For his part, Ravi was more interested in bringing Indian music together with Western traditions holistically rather than pulling out exotic motifs.

The same philosophy Ravi espoused for his collaborative duets with Yehudi Menuhin guided his creation and performance of Concerto for Sitar and Orchestra, which he debuted with the London Symphony Orchestra in January 1971.

Meanwhile, George Harrison had been experiencing significant changes in his musical career due to rising creative differences amongst The Beatles.

The band finally broke up in 1970, and given that George had been evolving his own unique, eclectic style of music and song writing, he launched his career as a solo artist.

His work continued to reflect his interest in Indian spirituality and music, which is especially evident in My Sweet Lord from his debut solo album All Things Must Pass, where he deftly combined dialects and ideologies from not one, but two spiritual traditions -- the Christian Hallelujah and the Hindu Hare Krishna Maha Mantra -- in the chorus of a pop song.

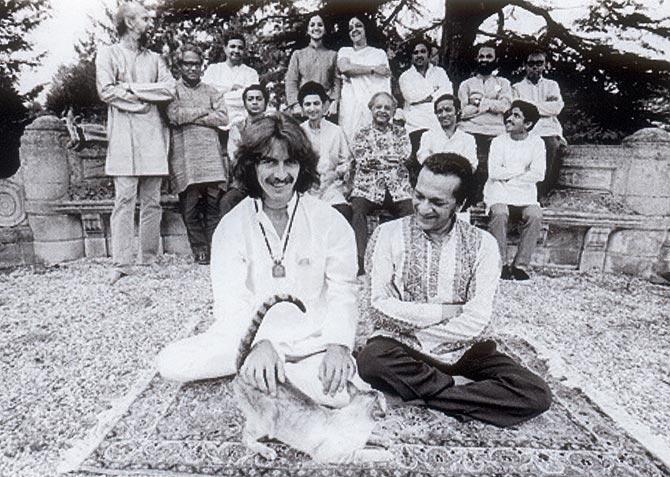

Through these difficult years, Ravi and George maintained their close friendship. And in 1971 that friendship changed the world.

As a Bengali, Ravi was troubled by the war that had devastated Bangladesh as it fought for independence from Pakistan.

He wanted to use his artistic platform to help in some way and decided to hold a concert.

Ravi turned to George, hoping that he would participate. George did more than that; he took on much of the planning for the concert and asked many of his rock 'n' roll friends to participate.

The concert was planned for August 1, 1971 at the Madison Square Garden arena in New York City, but the demand was so high that a second concert was added on the same day.

The stellar line-up included such rock 'n' roll icons as former Beatles bandmate Ringo Starr, Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan and Billy Preston.

In addition, George wrote and released a single, Bangla Des', just in time for the concert.

He was concerned that the central purpose of the concert -- to raise awareness and money for Bangladesh -- along with the person who was its initiator -- Ravi shouldn't get lost amidst the flash and flare of the participating rock stars.

So the concert kicked off with a jugalbandi performance between Ravi and Ali Akbar Khan, whom Ravi invited because Allauddin Khan, their mutual guru and Ali Akbar's father, hailed from Bangladesh.

Legendary music producer Phil Spector, who produced the award-winning concert album, described the ground-breaking nature of the Concert for Bangladesh:

'It was the first of its kind benefit by stars for a relief concert and it was magical.'

'That's the only word to describe it because nobody had ever seen anything like that before, that amount of star power on stage since Woodstock.'

'And this was all onstage in two hours, onstage at one time. Eric (Clapton) was there, Leon Russell was there, Ringo (Starr) was there.'

Beyond the tremendous buzz generated around the concert, it also managed to create greater awareness for the plight of the nascent country of Bangladesh.

Also, instead of raising tens of thousands of dollars, as Ravi had initially hoped, the concert raised millions.

There is no denying that, on an artistic level, this concert was a pivotal moment for Indian music in the West. The album also received a Grammy for Album of the Year in 1972.

Excerpted from Poignant Song: The Life And Music Of Lakshmi Shankar by Kavita Das, with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.