September 12 marked the 122th anniversary of one of the most incredible battles in Indian history.

Ritwik Sharma looks back at how we remember the Battle of Saragarhi.

Havildar Ishar Singh has been rescued from the oblivion that he had been consigned to for more than a century.

There are no photographs of the sergeant or the handful of Sikh soldiers he led at a small outpost in one of modern history's bravest last stands.

A stone bust at his native village of Jhorran in Ludhiana district, too, lies in obscurity.

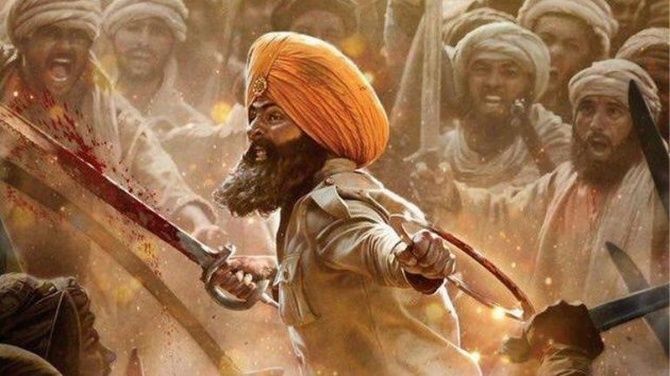

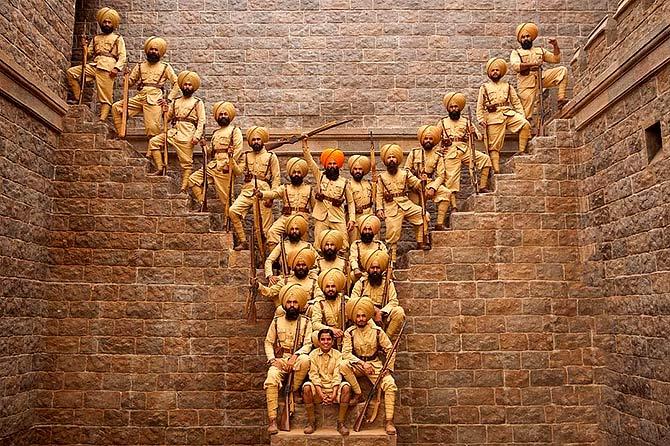

However, with the release of the Akshay Kumar starrer Kesari, the memory of Ishar Singh and the other martyrs is being recast at a time when episodes from military history such as the Battle of Saragarhi are getting more attention in Punjab and beyond.

The battle, which was fought on September 12, 1897, in the North-West Frontier Province in present-day Pakistan, has long been little more than a footnote in history.

People in Punjab have heard of how 21 Sikh soldiers of the British Indian army died fighting an enemy of 10,000 tribesmen.

But Akhtiar Singh, a retired schoolteacher who is settled in Canada and spends a few months in Jhorran every year, points out that no one takes much interest in the story.

The memorial with Ishar Singh's bust on a marble plinth next to a gurdwara stands where he was born and raised.

He died aged 39, and had no children. His grand-nephew Bikkar Singh's family organises commemorative functions around September 12 that include Akhand Path (non-stop recitation of all verses in the Guru Granth Sahib) for three days, which is followed by a gun salute by the Indian Army.

Santokh Singh, 26, Ishar Singh's great grand-nephew, says when the British government sent letters informing them of their sacrifice, the martyrs' families -- mostly illiterate -- became worried.

"They thought the letters meant they could be picked up or their land snatched," he adds.

In the family, the generations that came after Ishar Singh have been farmers.

Santokh Singh says he wanted to join the army, but his parents talked him out of it.

The colonial government posthumously awarded the 21 soldiers with the Indian Order of Merit, the highest gallantry award that an Indian soldier could receive at the time.

The Saragarhi martyrs' families were also given two murabbas (50 acres) and Rs 500 each.

The family of sepoy Sahib Singh came from Pakistan to India during Partition.

Avtar Singh, Sahib Singh's great great-grandson, owns a real estate business and farmland.

His maternal grandfather moved to Ludhiana from Pakistan and brought along the hero's portrait to set up a memorial at their new home.

They, too, organise communal meals and religious recitations on the anniversary of Saragarhi.

The practices of remembrance and the legacy of Saragarhi have transformed the martyrs into mythical figures -- part soldier, part saint.

All units of the Indian Army's Sikh Regiment observe September 12 as the Regimental Battle Honour Day.

The martyrs were part of the 36th Sikhs (now the 4th battalion of the Sikh Regiment).

In the UK, the British Armed Forces have commemorated the date as Saragarhi Day since 2014.

After assuming office two years ago, Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh announced a state holiday on Saragarhi Day.

The British built two gurdwaras to commemorate the soldiers: One, close to the Golden Temple in Amritsar, and the other in Ferozepur. Most of these soldiers belonged to Ferozepur.

The gurdwara in Ferozepur is part of the cantonment in this border town dotted with war memorials.

Built in 1904, around the same time as the one in Amritsar, the gurdwara is a white and red memorial building with cannons positioned in front of it.

A separate building in a corner with a large hall, lush lawns, banyan trees and flowerbeds is part of the expansive public space.

Tarlochan Singh, who works with a telecom company nearby, visits the shrine daily during lunchtime.

"I like the peaceful environment here. People come to this place a lot. We take pride in the history of Saragarhi, although we don't know much about the martyrs," he says.

He washes his feet and hands at the tap outside before entering the gurdwara.

A bunch of boys in school uniform follows him soon after. At one end of a lawn, two families meet and chat to explore matchmaking possibilities.

For most people, it is the spiritual pull or mere convenience rather than an interest in history that draws them to the gurdwara.

For the last three years, the families of some of the Saragarhi martyrs have been going to Ferozepur at each anniversary, says Avtar Singh, adding that the Congress government in the state has given it more importance.

At these events, the state honours the descendants. The last time they were given a kirpan, loi (blanket/shawl) and siropa (honorary length of cloth).

Saragarhi, a hamlet in the border district of Kohat on the Samana range in what is now Pakistan, was the site of a bloody face-off between the Sikh soldiers and Pashtun Orakzai tribesmen.

In August 1897, the British sent five companies of the 36th Sikhs under Lieutenant Colonel John Haughton to the North-West Frontier Province (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa).

Tribal Pashtuns attacked the British repeatedly, although the latter succeeded in controlling the area.

They had consolidated a series of forts, built by Sikh ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Two of these, Fort Lockhart and Fort Gulistan, were located a few miles apart. Saragarhi was created midway, as a heliographic communication post.

An uprising by the Afghans began in 1897, and after attacks on Fort Gulistan that were foiled, they surrounded Saragarhi where they admitted to having lost 180 men in the battle.

Afterwards, they aimed to conquer Fort Gulistan. But the long battle had delayed them enough to allow reinforcements to arrive at Fort Gulistan in time to thwart any further attack.

Captain Amarinder Singh, a former army man who served in the Sikh Regiment, has also authored a book, Saragarhi and the Defence of the Samana Forts: The 36th Sikhs in the Tirah Campaign 1897-98 (2017).

In it, he pays tribute to a non-combatant named Dadh, a Pathan likely from those parts who was the cook at the fort, but who went on to kill at least six of the enemy before losing his life.

In director Anurag Singh's Kesari, a fictionalised account of the battle, the cook's character begs Ishar Singh (Kumar) to allow him to join their combat.

But the sergeant urges him to offer water to the injured soldiers, including from the enemy.

Ishar Singh's raison d'etre in the movie is to uphold his Sikh identity, and he believes he's expressing freedom by choosing to die not for the British rulers -- who advise him and his men to escape from the fort -- but for his qaum (religion).

And although Kesari tries to convey a religious message of fraternity, it does so by largely projecting the Sikh and Muslim in broad strokes of good and evil binaries.

Apart from Kesari, another Bollywood film, Sons of Sardaar, starring Ajay Devgn, is in the works.

There has been an effort in Punjab, with Amarinder Singh's initiatives, to popularise military history and bring it closer to people.

Indu Banga, emeritus professor of history at Panjab University, says a movie like Kesari could be part of that general effort.

The growing awareness about the Battle of Saragarhi emphasises valour and martial spirit of the Sikhs, which could be traced back to the 18th-century Sikh history post-Guru Gobind Singh -- the founder of the Khalsa, says Banga.

"The martial spirit, the spirit of self-sacrifice and the idea of martyrdom were dominant in the political struggle against the Mughals and Afghans then," she adds.

The sheer valour displayed at Saragarhi is indubitable, but there remains both a lack of awareness and contestation of its historical facts.

Rameshwar Singh, a retired Punjabi lecturer based in Ferozepur, says people do not know where the battle was fought and that Dadh was neither posthumously honoured nor remembered by anyone.

"Had the Afghans won the battle, the place would have gone to Afghanistan and not Pakistan, which was then part of British India. So although some say the Sikhs fought for the British, in a sense they fought for the country," he says.

Of all the martyrs, the families of only eight have been identified so far, says Rameshwar Singh.

These families assemble every September in Ferozepur.

Two years ago, the state government entrusted the task of the memorial's upkeep with a trust comprising army men.

Rameshwar Singh says under the army, the commemoration event largely excludes ordinary people.

Besides India and the UK, Saragarhi is celebrated in Canada and America.

Jagmohan Singh, an academic and nephew of freedom fighter Bhagat Singh, argues that the Republicans and the Conservatives tend to valourise the martyrs with a mindset of "you are great because you fought for us".

In Punjab, Saragarhi is only memorialised by the army, not the common man. "For the army, it's about a Sikh unit."

The fact that the British army failed to support the 22 men (including Dadh) in Saragarhi and abandoned them in the face of adversity must be questioned, he says, adding that "in our history we leave the British out and blame each other".

After the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, the British India army started recognising Sikhs, among some others, as a martial race.

Jagmohan Singh argues that for the British it was a ploy to win their loyalty by offering awards such as land grants.

He cautions that with popular culture and media, we are drumming up a war psyche as patriotism and nationalism have become dominant themes in our public discourse.

But, he adds, we would do well to question who one is fighting for even as we acknowledge genuine valour.

As Kesari dug up Saragarhi from the vaults of history, it carved a new mythology of Ishar Singh. One that eclipses the distant memory of his life and time, even among his own descendants.