Neither Modi nor Shah had held legislative or executive power in Delhi before 2014.

They have no training in appealing to the diversity of India as represented in Parliament.

Their prism is the provincial politics of Gujarat.

An exclusive excerpt from Vinay Sitapati's fascinating new book, Jugalbandi: The BJP Before Modi.

Where Vajpayee and Advani sought to appeal to both the moderate and the radical, there was no such electoral incentive for Modi and Shah.

If today's BJP is less upper caste than the BJP of old, it is also more anti-Muslim.

How does the Vajpayee-Advani partnership compare with the evolving one between Narendra Modi and Amit Shah?

To answer that question, one must go back to the periods in which they entered politics.

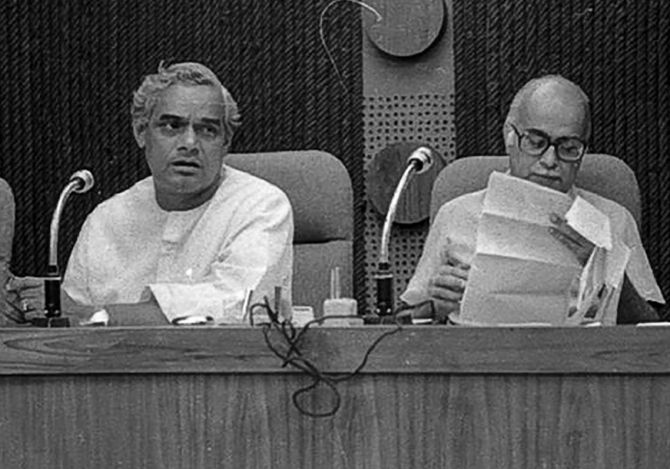

Vajpayee and Advani came of age in the Delhi of the 1950s. It was a time in which the Nehruvian consensus was shared even by the non-Congress opposition.

The murder of Gandhi, the leader of India's Hindus, had rendered the RSS and Jana Sangh untouchable. Vajpayee and Advani's primary task was limited to making Hindutva respectable again.

This context made both realise that Hindu nationalism had to 'moderate' itself, reconcile itself to the mores of Nehruvian India, if it hoped to win voters. This was their default position through the next several decades in politics.

Even at the height of the rath yatra -- with Hindus radicalised like never before --Advani pulled back from the edge. There was a line he would not cross.

In contrast, Modi and Amit Shah had their political education in the Gujarat of the late 1970s and early '80s.

Rising lower castes were threatening to split Hindus and the Congress was rebooting by uniting Muslims and low-caste Hindus against upper castes.

Modi and Amit Shah's answer was to radicalise their politics by underplaying caste and overplaying Islamophobia -- all in order to fuse enough Hindus into voting for the BJP.

Where Vajpayee and Advani sought to appeal to both the moderate and the radical, there was no such electoral incentive for Modi and Shah.

These formative years inform their politics even today.

Modi and Shah are more astute in catering to low castes microscopically as well as attacking Muslims macroscopically.

Though Vajpayee and Advani were as alive to the demographic anxieties that animate the recent Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens, they would have both balked from such overt hostility to India's 200 million Muslims.

If today's BJP is less upper caste than the BJP of old, it is also more anti-Muslim.

The other reason for this divergence between the two partnerships is that Vajpayee and Advani spent decades in Parliament in Delhi.

In contrast, neither Modi nor Shah had held legislative or executive power in Delhi before 2014. They have no training in appealing to the diversity of India as represented in Parliament.

Their prism is the provincial politics of Gujarat.

The result is that Modi-Shah are more ruthless to political opponents than Vajpayee-Advani ever were.

***

The political context in which these two relationships began have brought out contrasting attitudes to winning and keeping power.

But Vajpayee-Advani and Modi-Shah also share more than is imagined.

While there are indeed disparities in their treatment of those outside the party, what both duos share is an emphasis on outward displays of internal unity..

If Vajpayee-Advani and Modi-Shah share the same attitude to sticking together, even their record in governance is not all that different.

On the ideological issues of Article 370 of the Constitution, a Uniform Civil Code and a Ram temple at Ayodhya, the Modi government might seem more determined. But much of this can be explained by the compulsions of coalition politics during the Vajpayee era.

In contrast, the Modi government has the freedom, and numbers, to follow ideology.

There are, however, a few areas of governance where the personalities of the two sets of partners have produced divergent results.

This is most obviously so on the economy.

India's economic performance under Vajpayee was so good that they were even fooled into fighting an election on it.

On the other hand, Modi's economic performance, especially in the years 2019-20, has been so bad that Modi never campaigns on it.

Vajpayee was large-hearted enough to allow his own Cabinet or party to debate and even criticise his economic policies. He trusted specialists to do their job.

In contrast, the man who marketed himself as Mr Development in Gujarat seems to have contempt for economics as a specialist field, trusts few experts and is forever balancing economics with political expediency.

Few in his cabinet, let alone his party, are encouraged to speak truth to power.

On the flip side, Modi seems to have a better feel for welfare schemes and the farm sector than the Vajpayee government did. This is perhaps why (in addition to Hindutva) Modi-Shah were re-elected in 2019, while Vajpayee-Advani lost in 2004.

Modinomics may be bad for the economy, but it seems adept at garnering votes.

Modi's better connect with the voter leads to perhaps the most telling difference between the two eras of the BJP.

Modi's better connect with the voter leads to perhaps the most telling difference between the two eras of the BJP.

While Vajpayee was adept at divining the mood of parliamentarians and Advani of the party worker, both lacked the daily contact with ordinary Indians that Modi has worked on for decades.

In that sense, neither Vajpayee nor Advani were mass leaders.

Modi, on the other hand, has an almost mystical connect with the voter.

The prime minister he is most like is Indira Gandhi.

Footnotes have been redacted in this exclusive excerpt.

Excerpted from Jugalbandi: The BJP Before Modi by Vinay Sitapati, with the kind permission of the publishers, Penguin Random House India.

Order your copy here.