People on both sides of the Hindutva debate need to read and understand the texts first, Bibek Debroy, translator of the unabridged Mahabharata, tells Kanika Datta as he gets started on a similar project for the Ramayana.

Most scholars would consider it a lifetime's achievement to translate the 90,000 shlokas of the Mahabharata. But Bibek Debroy, economist and member of the NITI Aayog, the Planning Commission's successor organisation, hopes to do a double by next year.

Having completed a highly praised 10-volume English translation of Ved Vyas' Mahabharata in 2015, he is in the throes of translating the unabridged version of Valmiki's Ramayana.

As a prolific newspaper columnist, Debroy's views on the economy and the Railways, his particular brief at NITI Aayog, are well known. This lunch, at Varq, the 'fusion' Indian food restaurant at the Taj Mahal Hotel in central Delhi, is about this second challenging intellectual undertaking.

The Ramayana project nearly didn't materialise, he tells me over a preprandial glass of the house wine.

For the Mahabharata translation, he worked from the critical edition of the text available at The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute in Pune. For the Ramayana, he was aware that the Oriental Institute at the University of Baroda had come out with a critical edition, but it was nowhere to be found. Five years of searching, including activating government sources, yielded no luck.

"Then I joined NITI Aayog and had no time to think about the Ramayana."

With great nobility I refrain from taxing him about his robust denials of a role in Yojana Bhavan, as the headquarters of NITI Aayog were then called, when we met in 2014 in the interest of listening to the extraordinarily fortuitous turn of events that resulted in the Ramayana project.

In mid-2015, he was reading a Sanskrit text on a flight; so was the passenger next to him. "Imagine," he marvels, "if the probability of one person reading Sanskrit on a flight is low, that of two guys reading it is almost zero!"

His fellow passenger was Shailendra Mehta, former IIM-Ahmedabad professor, currently vice- chancellor of Ahmedabad University, an expert on Tantric Buddhism and currently writing a history of Indian math.

They talked about Debroy's difficulties with the Ramayana. Three months later, Mehta walked into Debroy's office dragging a trolley bag. In it reposed seven densely printed volumes of the complete Baroda critical edition. Mehta had travelled to different parts of India to collect them.

'All yours,' he told Debroy, with the proviso that they be donated to the India International Centre library when he was done. For Debroy, this was a call of destiny that he could not ignore, so he got started.

The plan is to submit to Penguin, the publisher, the manuscript for a three-volume edition by the end of this calendar year.

This should have been a breeze.

In contrast to the 1.25 million-odd words that went into the Mahabharata, these three Ramayana volumes will have roughly 750,000 words.

For the Mahabharata, he worked most evenings and weekends with his dog for company with a target of 1,500 to 2,000 words a day for five-and-a-half years. Now, his NITI Aayog job makes it near-impossible for him to do the same; the only opportunity to work is on flights and during free time in hotel rooms. With the result, he laughs, "I am travelling everywhere with the Ramayana!"

We have ordered the set 'Varqui lunch': Mustard prawn for both of us, and a sukka mutton, lamb flavoured with black pepper, onions and curry leaves, starter for me and fruit platter for afters for him.

I remember him saying how much he would miss the Mahabharata characters when his work was done. Had the experience changed him?

He thinks long enough to swallow an amuse-bouche -- pointless, intricately prepared hors d'oeuvres so minute as to elude the taste buds. Not consciously, he answers, but says his wife has commented that he has become detached to the point that he finds "many transient things don't matter anymore."

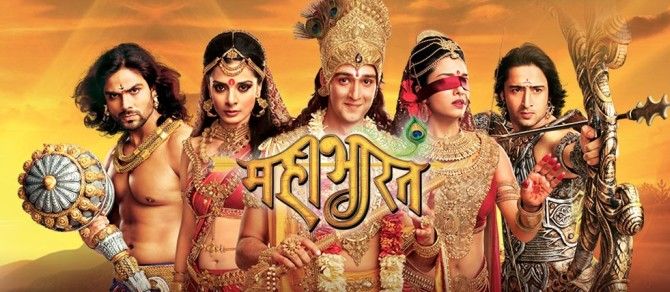

This, despite the very temporal blood and gore of the epic, I wonder. "That's what the abridged versions have reduced it to," he counters. "The Mahabharata is fundamentally a religious text -- and I use the term in an enlightened philosophical, and spiritual sense."

Anticipating the obvious 'compare and contrast' question, he adds, "Beyond that the Mahabharata is about poetry -- but it is no patch on the quality of poetry in the Ramayana, which is simply superb."

Which gives me the opportunity to ask another classic Muggles question: Which of the two were more profound in terms of philosophy? "Roughly one-third of the Mahabharata has extended treatise on metaphysics, governance and so on; in fact, other than the Bhagvad Gita, there are at least 11 other Gitas in the text -- and there are huge sections on geography. In the Valmiki Ramayana so far," -- he has translated as far as the Ayodhya Kanda -- "these things are missing."

The mention of geography makes me recall the replication of both myths in temples in Indo-China, but the Ramayana is more prevalent there. Before answering, he waits for my starter to be served and agrees to share a little of the large but exquisitely prepared portion.

Vacationing in Russia, he met an Indian who was married to a Russian woman from Kavkaz -- the Caucasus -- who he claimed was a Hindu. How? Was she from ISKCON? No, the man replied, they believe that this is where Kaikeyi -- Rama's troublesome 'younger mother' -- was born and Kavkaz is a derivative of her name.

"It's conceivable," Debroy says, "because Kaikeyi has never been unambiguously identified. The reason I brought this up is that the terrain covered by the Mahabharata is narrow -- essentially between the Ganga and the Yamuna -- whereas the Ramayana's geographical expanse is much wider. Plus, there were extensive trade links between south India and South-East Asia that spread these stories, including the Buddhist Jataka stories."

Given the heavy metaphysical bias in the Mahabharata, did his academic training as an economist influence him?

There are some instinctive reactions, he admits. "If the Mahabharata says the distance to the moon is such-and-such I can't resist the temptation to put in a footnote saying, 'therefore the value of Pi works out to this.' Or if Bhishma is instructing Yudhisthira and lists the most important civil cases he must remember, I can't help flagging that breach of contract tops the list."

This brisk academic tone continues when I ask him how he reconciles the narrow view of Hinduism that informs the support base of the regime he serves with the broad-ranging metaphysics to which he has gained a unique insight.

He is certainly irritated by the fact that he gets branded as possessing a certain kind of view because of his interests. But, he says, the anti-Hindutva view is equally narrow. His overall point: "All kinds of people on either side of the debate shoot their mouths off on Hinduism without bothering to understand or read it."

He warms to his theme as the prawn is served.

Consider the claims of India's access to high-tech in ancient times -- as exemplified by references to vimanas (airplanes) and divyastra (supposedly a nuclear weapon). "The obvious point that has been missed is that the texts do not say humans had this technology but that it came from the gods. The texts actually describe a classic less developed country-developed country syndrome, in which primary products are offered in return for access to technology."

This ignorance extends to food habits he says.

Aha, I think, we're on the beef ban and we quickly order a second glass of wine to wash down the prawn curry, which is decent if you're not comparing it with the Bengali equivalent.

One battle he fought on Twitter followed a visit to a village in Meghalaya where his hostess insisted on serving him a lunch of rice and pork, standard fare there. He was exasperated when people asked him how he could eat non-vegetarian food while translating the Mahabharata.

For the record, he has eaten beef in the past but doesn't eat it any more than he does other red meats, including lamb and pork. "It's not a religious thing, just old age, I guess." He also thinks the beef ban is misunderstood. "It's actually in the Directive Principles of State policy in a section relating to improving animal husbandry." I badly want to argue, but let that pass because time is running out.

The Ramayana translation is only one of several "lunacies" to which Debroy has succumbed.

A translation of the Harivamsha, a sort of epilogue to the Mahabharata, is due in September.

Then there's a co-authored anecdotal history of the Railways due October.

And after the Ramayana is a translation of the unabridged Maha Puranas -- at 400,000 shlokas, that's four times the size of the Mahabharata.

And after this lunch, he's off to yet another meeting. Maybe he gets his energy from all that weighty metaphysics, I think enviously, as I focus on the distinctly non-spiritual problem of returning to the office mildly tiddly.