'The blood that runs in the veins of our family can never be anti-national.'

'They called Kanhaiya a traitor for questioning the Indian Army. Do they know that our cousin was killed by militants in Manipur while serving with the CRPF?'

Kanhaiya Kumar will eventually leave the headlines, but on the verandah of his family home in Bihat, he will be in the news for a long time.

For the old comrades in the village -- also known as 'Bihar's Leningrad' -- clinging to the vestiges of Communism, Kanhaiya has stoked Marxism's dying red embers, at least for now.

Archana Masih/Rediff.com travels to the land of Lal Salam, Lal Sitara and comrades to find out what moulded India's most talked about student leader.

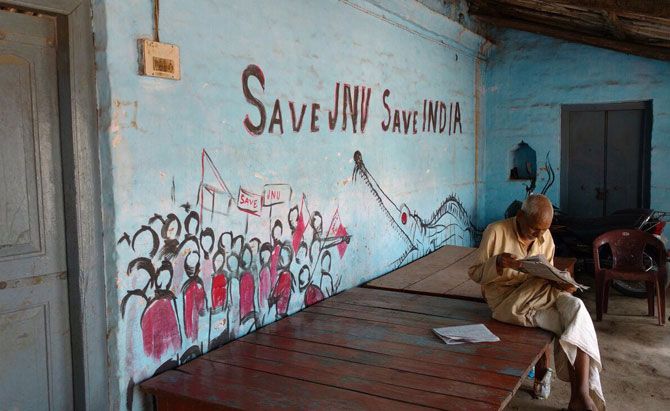

Kanhaiya Kumar's 66-year-old run-down family home welcomes friends and strangers with revolutionary slogans. They leap out of the walls and pillars that support a thatched roof under which live three branches of the extended family -- two rooms allocated to each family.

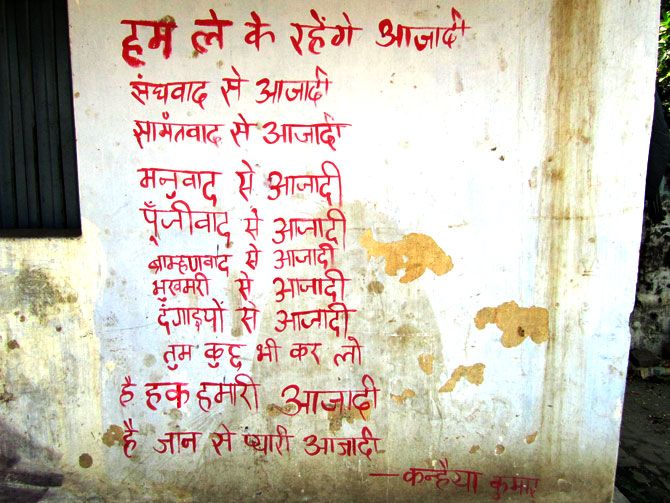

The slogans are terse: 'Lal Sitara'; 'Red Salute'; 'Save JNU, Save India'; 'Hum leke rahengey azadi' -- and accompany the face of the family's best-known member, Kanhaiya, painted in red and black on the front wall.

His right arm is raised as he gives a speech to a bunch of students, their hands ending in a fist high above their heads.

A fluttering CPI flag can be seen from the inner courtyard.

After his arrest, students from Santiniketan and the Patna Arts College had come by to paint the slogans. The colours and words provide a backdrop to the family's open verandah where two wooden plank beds and plastic chairs have given refuge to all kinds of occupants since the family's boy made national headlines.

This morning, Ravindra Mishra, who owns a medical shop in Azamgarh in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh, has come to extend support to the family. He peppers his conversation with poetry about an iron-fisted State intent on crushing the soaring cry of dissent.

'Par kate panchi sa lekin, hauslon ki yeh udan?

Yeh hakumat ke khilaf bahut likhta hai.'

The medicine seller and poet tells the family he would have come earlier, but did not get a train ticket. His return journey is by the next day's train and since he is a stranger in the village and has made no arrangements for accommodation, Prince Kumar, Kanhaiya's younger brother, asks him to stay with the family.

The verandah is occupied by brothers, uncles, cousins and Rajendra Singh, 84, the white haired, dhoti-clad dadaji, brother of Kanhaiya Kumar's grandfather.

A committed Marxist, Rajendra Singh is a repository of information about the history of Communism in Bihar and is related to Chandrashekhar Singh, the first Communist MLA elected in Bihar, in a 1956 by-election.

The son of powerful Congress leader Ramcharitra Singh, a minister in the cabinet of Bihar's first chief minister, Chandrashekhar Singh was chiselled by the zeal of azadi as a student at the Banaras Hindu University and is seen as the harbinger of the Red Star in Bihar.

"He was the first post graduate from the old Munger district. While his father's room had books that complemented the ideology of the Congress, his son's room was full of Marxist reading," remembers Rajendra Singh, lending perspective to the two streams of thought co-existing under the same roof.

A legend in Begusarai-Munger, Chandrashekhar Singh has a library, a gate and square named after him in Bihat, also known as 'Bihar's Leningrad'.

The CPI had an interrupted victory run in every state election till 2010, and has lost only two elections in Bihat, which fell in the Barauni assembly till delimitation and is now part of the Teghra constituency. The present legislator is from Laloo Yadav's RJD.

This land was the foundation of Communism in Bihar, explains the elder and gives me a magazine commemorating Chandrashekhar Singh's centenary.

Bihat's main square is festooned with red hammer and sickle CPI flags, while a new gate is being built in Chandrashekhar Singh's memory after the old one broke down. It will cost around Rs 12 lakhs (Rs 1.2 million) for which money has been raised by collecting donations.

Chandrashekhar Singh is also related to Kanhaiya Kumar.

"This battle is about ideology and it will be a long drawn one," says Rajendra Singh, who is joined by Kanhaiya's uncle Pramod Singh, a retired teacher whose son serves in the army.

"Hum sochey ki ab hamarey bacche ki hathya kar dalega, Pramod Singh says, that the family feared their boy would get killed that day in the Patiala House court.

"Behind branding him anti-national is a well-thought out plan," says Pramod Singh, speaking calmly as a teacher explaining to a class, "They know the Left parties are strong in the states that are going to the polls. By calling Kanhaiya anti-national, they want to brand the entire Left as anti-national."

"Ek Kanhaiya ko vidrohi karar kar ke, uski shahadat kar key, yeh log rajnitik labh uthana chahte hai (They want to sacrifice him on the altar of nationalism and reap political gains)," but he is our blood and we have unflinching faith in him," says Pramod Singh.

"The blood that runs in the veins of our family can never be anti-national."

Past the inner courtyard with a Tulsi plant and a couple of stone hand grain grinders is a dimly lit room which has been Kanhaiya Kumar's father Jaishankar Singh's world since paralysis struck his left limbs.

A television set is placed in front of his bed and when the tin door leading to the bathroom outside is left open, more light enters the room.

"What pained me most was when they called my son a deshdrohi," he says, tears welling in his eyes.

"Kanhaiya ki bhasha mein koi bhi deshdroh wala baat nahi tha. (There was nothing in Kanhaiya's words that indicated treason)," he says, adding that his son was always very good at debate and he felt proud of his post-release stirring speech.

"Jis din riha hua, aath dukan ka abeer khatam ho gaya." Eight shops in Bihat had run out of Holi colours when Kanhaiya was released from Tihar jail, says Jaishankar Singh.

In the days when his limbs were strong, he worked odd jobs -- sometimes as a driver, taking a small contract to load stone chips -- to sustain his family.

In Bihar where caste lines run deep, the family comes from the upper Bhumihar caste which is the dominant caste in Bihat. Many of the village's residents are employed in government jobs. Kanhaiya's family has several teachers, especially among the women folk. Five or six of his cousins serve in the army and paramilitary.

"They called Kanhaiya a traitor for questioning the Indian Army. Do they know that our cousin was killed by militants in Manipur while serving with the CRPF?" asks Prince Kumar.

Martyred cousin Dilip Kumar's garlanded photograph hangs outside the village library named after Chandrashekhar Singh.

The trooper's widow lives in the CRPF camp in Mokama, but Prince Kumar says she is being pressurised to vacate it.

"Yeh sarkar ka do charitra hai." The government is two-faced, he says, "in front of the media it says it respects a soldier's martyrdom, but on the other hand, it asks a martyr's widow to get out."

A short walk from the photograph of the martyred jawan is the government-run day-care centre where Kanhaiya's mother Meena Devi goes to work every morning. It stands opposite an old house that belongs to Chandrashekhar Singh's family.

No one lives in the house anymore. Peeping through the bars of the iron gate, Prince Kumar says village elders recount stories of the comrade's wife Shakuntala, a graduate and daughter of a renowned Congressi, playing badminton on the front lawn in pre-Independence Bihat.

Meena Devi is standing in the creche, as a group of toddlers await their morning snack of government provided halwa.

She earns Rs 3,000 and hasn't been paid in three months. The family's income is supplemented by elder son Manikant's earnings as a factory worker in Assam.

Manikant rushed to Bihat after Kanhaiya's arrest and plans to return after Holi. He has been working in Assam for 10 or 12 years, leaving his wife and children behind in the family home in the village.

"Money was hard to come by, but we never put any pressure on Kanhaiya or his brothers to stop studying and get a job to support the family," says Kanhaiya's mother Meena Devi.

When Kanhaiya called her after his release, it was the first time he had spoken to her in months. 'I have said nothing that will bring you disgrace,' she recalls him telling her in that phone conversation. The family has spoken to him two or three times since then and keep up with news about him through the news or through friends.

The day I was there, a cousin posted with the CISF in Delhi had paid Kanhaiya a visit. He had subsequently called the family and conveyed the minutes of the meeting.

The family is keen to see Kanhiaya, but are unsure if he can come to Bihat after threats of cutting off his tongue and a reward for his murder were issued.

"Even when he was in college, Kanhaiya used to say that he wants to be like a tree with dense leaves that can provide shade to many," smiles Meena Devi, wearing the white sari with a white border stipulated for government anganwadi workers.

"I might take mummy to Delhi to meet him," says Prince Kumar, reiterating that the family's greatest concern at the moment is Kanhaiya's safety. Their home has been provided with police protection, security personnel in plain clothes.

"This is no longer a battle of ideology, it has taken a violent form," says uncle Pramod Singh, the retired school teacher. "Be it deceit or by incitement, the government is vitiating public discourse against Kanhaiya."

The family has been collecting newspapers with news about Kanhaiya and give me a booklet published by the CPI, 'Fascist hamle ka pratirodh karo (Oppose the Fascist attack)' which has Kanhaiya's photograph on the front and back cover.

In Bihat bazaar, by the shadow of the statues and names of Communist stalwarts, two comrades discuss the latest Hindi edition of India Today which has a story on Kanhaiya in it.

Since his arrest, journalists have been calling and dropping in for information. A local television channel was waiting the day I was there; the previous day, a reporter from a Marathi newspaper had come, while another reporter had travelled from Bengal and told them that he had heard they have two palatial houses.

"There are so many rumours floating. We have a dilapidated house and not even 5 kathas of land. Even that recent picture of a lady with Kanhaiya that went viral," says Prince Kumar, referring to the photograph of a lady with her arm around Kanhaiya. "She is a culture activist at JNU and it was her birthday that day."

The man from Azamgarh, who has been listening to the conversation for a long time, asks if they felt Umar Khalid, the JNU student still imprisoned for sedition, was also innocent of the charges filed against him by the government.

"Kanhaiya bhi nirdosh nahi hai kyu ki case abhi adalat mein hai par iski nishpaksh jaach honi chahiye." Kanhaiya hasn't been declared innocent yet and the case is in court, but there should be a fair investigation, says Prince Kumar.

"Kanhaiya par hamla ho jata hai aur Umar toh Muslim hai. Usko toh maar hi detey. Muslim hone ka toh chukana padta, yeh sthithi hai is desh ki." If Kanhaiya could be attacked, Umar would have been killed. Muslims have to bear the cost of being Muslims, such is the state of this country today, says Prince Kumar mournfully.

JNU is being projected as a den of atankwadis (terrorists), says Prince Kumar, it is not so, speaking with the confidence of a seasoned political activist.

"JNU kikiri hai BJP ke liye. Mamla JNU ka bhi hai, sirf Kanhaiya ka nahi hai." JNU is a thorn in the eyes of the BJP, he says. JNU is as much an issue as Kanhaiya.

The MCom graduate wonders why Jadavpur University, which saw similar protests, has not been in the news like JNU. Pramod Singh, the retired teacher and Kanhiaya's uncle, asks why the sarkar, with all the investigative agencies at its disposal, has not been able to arrest those who really raised the slogans.

"Rajnath Singh gave a statement based on a fake tweet that Kanhaiya is involved with Hafiz Sayeed. Should he not have retracted his statement? Till date he hasn't," says Pramod Singh, sitting cross legged on a bed in Kanhaiya's father's room.

Jaishankar Singh, Kanhaiya's father, is sitting in a chair. He doesn't speak much and when he does, his eyes moisten with tears. I ask him if he would like to see his son and he replies that Kanhaiya's janta is in JNU.

I then ask if he would like Kanhaiya to enter politics and he says it is for his son to decide.

He should complete his PhD first, says older brother Manikant, while younger brother Prince says, "He is a member of the party and there is a possibility that the party might ask him to contest in the future," but only after the PhD.

There is one more year for Kanhaiya to complete his PhD.

"Woh bola hai ki hum neta nahi hai, hum vidhyarthi hai aur jo hum padhte hai uske liye hum awaz uthate hai." He has said he is a student and not a politician, says 'Dadaji' Rajendra Singh, he will raise his voice based on what he reads in books.

I ask them if they thought Kanhaiya's sheen would wear off if he were to enter politics because much of his support comes from the fact that he is a student.

"People support him for what he says, rather than who he is," says Prince Kumar and recounts the time when Kanhaiya told his Class 5 teacher that he wanted to be a 'political activist.'

"Kanhaiya has injected fresh energy into our movement," says Ram Ratan Singh, an old Communist with an undeterred faith that India's poor can only be lifted out of poverty by the Marxists and not by a "punjiwadi sarkar (capitalist government)."

The family wears its allegiance to the CPI with pride.

Prince says Kanhaiya and he used to campaign for CPI candidates as children and actively participated in plays staged by the Indian People's Theatre Association, the cultural wing of the CPI.

It was for the Bhisham Sahni play Kabira Khada Bazaar Mein that Kanhaiya received an award as a school boy from then CPI general secretary A B Bardhan, who passed away in January.

Kanhaiya has a responsibility in society, says Prince, who has taken me around the village, including the government primary school that Kanhaiya attended.

"Jis ladai ki baat ki hai usko ant tak pahuchana hai." He has to fight for the issues he has raised till he accomplishes his goal, says Prince.

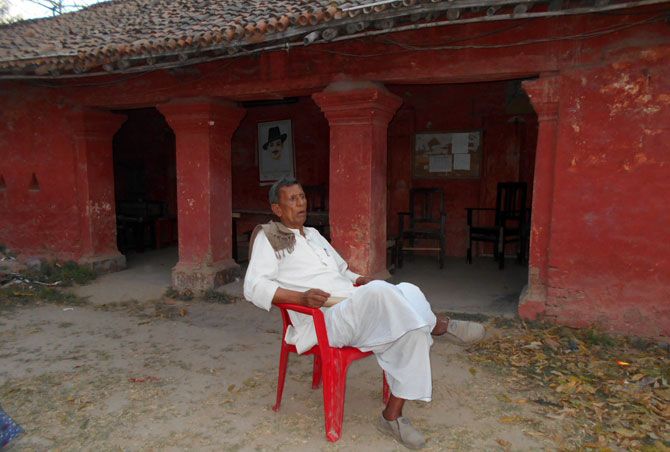

At the IPTA manch (stage) at the far end of a school campus, no one is in sight barring Ram Ratan Singh, the old comrade, who is reading a newspaper sitting in a red plastic chair.

Behind him is a poster of Bhagat Singh. Nearby is a flag post on which flutters a Communist flag. In front are two courts where a set of boys and girls play volleyball and net ball side by side.

IPTA, says Ram Ratan Singh, had staged a play the previous day and will perform again for Holi. IPTA, he adds, is not as active because of lack of funds and dismisses any questions on the relevance of Communism for a young India.

"Is strength only determined by numbers in Parliament or assembly?" he asks angrily. "The real strength of the Communist party is its cadre. In Begusarai we have 12,000 members," he adds, joined by some more elderly men who pull out more chairs as they settle down to read newspapers under a setting sun.

By virtue of its proximity to Barauni town, with its refinery, thermal station, fertiliser plant (which was shut down in 2002) and other factories, the Communists also drew strength from the trade unions. But their electoral influence has steadily waned. The current MP belongs to the BJP.

Yet there are more Communist flags in Bihat Bazaar than there are perhaps in the CPI head office in Delhi. They line shop entrances and criss-cross above the heads of local Communist leaders enclosed inside a memorial roundabout; while old dhoti-kurta clad Marxists refer to each other as "comrades" and fondly remember another time.

I ask the girls who have just finished their netball practice -- seven of them have been selected for the nationals -- what they thought of Kanhaiya Kumar. They say they had heard his slogans at the end of the post-Tihar speech but hadn't heard the full speech.

"If he has said anti-national slogans and they can prove it, then he should be punished," says coach Raj Kishore, "But a Hindu will never raise slogans praising Pakistan -- I don't think so."

Kanhaiya Kumar is the only person from Bihat to go to JNU. There were only 13 vacancies the year he had applied, says his brother.

The last time he came to Bihat was during the Bihar assembly election and then in December to campaign for the revocation of non-NET fellowships under the 'Occupy UGC' movement. He had spent a day at home.

His father had said debate was always Kanhaiya's strong point. It was what won him the JNU presidential election.

The CPI linked All India Student Federation was not very strong on the JNU campus, but it was the final debate where all contesting candidates had to take questions from students that clinched it for him, says Prince, who had attended that debate.

"One of the questions he was asked was how would he solve the problems of bed bugs," laughs Prince.

"Kanhaiya ke liye jo ladai lada hai, woh JNU ka 7,000 individual chhtra lada hai." The 7,000 individual students of JNU have fought for Kanhaiya, says Prince. The movement started by him went on to become a groundswell.

A day after we had this conversation, Kanhaiya Kumar was slapped and abused by an outsider inside JNU.

'You can kill me, you can silence me, but you cannot scare me,' Kanhaiya said addressing students later that day.

Every member of the family, I spoke to, said that their biggest worry was Kanhaiya's safety -- both on the campus and outside. Much as they take pride about him challenging a powerful State, those that are bound to him by blood agonise about his well being.

"We are sure there is no proof against him, but as long as this government has power, it will create problems for us," says his uncle Pramod Singh.

They sit in the verandah, its fading whitewashed walls restored by colourful graffiti and slogans. They talk about Kanhaiya and follow every piece of news, like they have done for over a month.

Kanhaiya Kumar will eventually leave the headlines, but on the verandah of his family home, he will be the news for a long time.

And for the old comrades of Bihat, clinging to the vestiges of Communism, Kanhaiya Kumar has sparked the dying red embers of Marxism, at least for now.