Visiting the Rezang La Memorial, one has a feeling of super-humans defending Indian territory against the Chinese onslaught, says Claude Arpi on the 60th anniversary of the heroic battle of the 1962 War.

Several years ago, I had the opportunity to interview one of the most renowned Indian mountaineers, who had chosen to live like local folks in the Himalaya.

She recounted an anecdote which took place during the All-Women Himalayan Traverse expedition; one day the expedition arrived in a small mountain village; speaking about the majestic surroundings, the mountaineer told one of the villagers: 'Kitne sundar! (How beautiful they are!)', the local pahari's immediate reply was, 'Kitna dukh! (So much suffering!)'

Somehow, the pithy phrase summarised the hard life in these high mountainous areas.

These words came back to mind when I recently visited the site of the the Battle of Rezang La, near Chushul village in Ladakh at more than 15,000 feet.

As one arrives by car from Nyoma, the track follows the imposing Kailash range, covered with snow.

Immediately, one is confronted by this paradox faced by one of the most peaceful and magnificent spots on earth, which has however witnessed some of the bloodiest battles since independence.

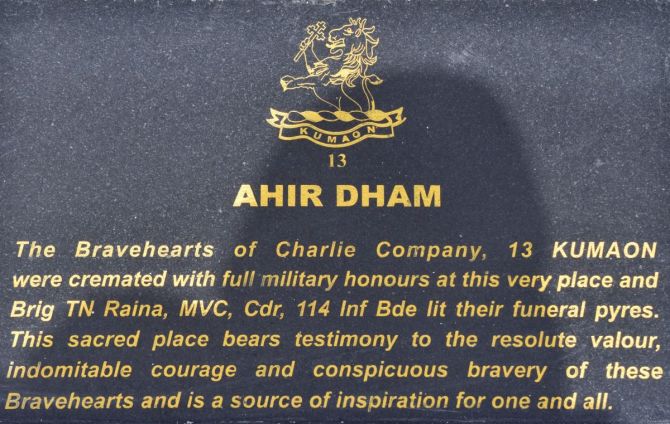

After crossing the Tsaga La (pass) and a few kilometers before arriving at the site of the newly-renovated War Memorial in honour of the 'Charlie' Company of the 13th Battalion of the Kumaon Regiment, one can have the magnificent sight of a Tri-colour flag floating in the blue sky.

The 'dukh' side

On November 18, 1962, a battle was fought at Rezang La at the incredible height of 16,000 feet, one of the greatest battles in history; 114 soldiers of the 124-strong company led by Major Shaitan Singh, Param Vir Chakra, lost their lives heroically defending the nearby Chushul airstrip, the last defence before Leh, Ladakh's capital.

Major Shaitan Singh was posthumously awarded the Param Vir Chakra, the highest military decoration; his battalion received eight Vir Chakras, four Sena Medals and one Mention-in-Dispatches, making it one of the highest decorated companies of the Indian Army.

The citation which appeared in the gazette, said: 'Major Shaitan Singh was commanding a company of an Ahir infantry battalion deployed at Rezang La in the Chusul sector at a height of about 16,000 feet. The locality was isolated from the main defended sector and consisted of five platoon-defended positions.

'On 18 November 1962, the Chinese forces subjected the company position to heavy artillery, mortar and small arms fire and attacked it in overwhelming strength in several successive waves. Against heavy odds, our troops beat back successive waves of enemy attack.'

It is further mentioned that 'Major Shaitan Singh dominated the scene of operations and moved at great personal risk from one platoon post to another sustaining the morale of his hard-pressed platoon posts.

'While doing so he was seriously wounded but continued to encourage and lead his men, who, following his brave example fought gallantly and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy. For every man lost to us, the enemy lost four or five.

'When Major Shaitan Singh fell disabled by wounds in his arms and abdomen, his men tried to evacuate him but they came under heavy machine-gun fire. Major Shaitan Singh then ordered his men to leave him to his fate in order to save their lives.

'Major Shaitan Singh's supreme courage, leadership and exemplary devotion to duty inspired his company to fight almost to the last man.'

Visiting the War Memorial, one has a feeling of super-humans defending the Indian territory against the Chinese onslaught; it is deeply touching; remember that most of the soldiers of the Charlie Company who fought the battle at this altitude had come from the plains of Haryana.

The Ladakh Range and particularly Rezang La and the nearly peaks/passes have an extraordinary strategic importance as they dominates the Spangur Tso (lake), the Spangur Gap (the narrow area between the Pangong Tso and the Spangur Tso) as well as the strategic road to Rutok, the main garrison in Western Tibet and the route to Leh.

By controlling these ridges, the Indian Army stopped the Chinese advance on Leh and probably saved Ladakh.

Incidentally, the cease-fire was declared by China four days later. Was it a coincidence?

Though still classified, parts of the Henderson-Brooks-Bhagat Report (hereafter the Report) on the 1962 conflict have found their way to the Internet. It is worth quoting some extracts.

In November 1961, a 'Forward Policy' was ordered by the Government; the Report commented: 'The 'Forward Policy' was primarily introduced to bunk the Chinese claims in Ladakh. Had the developments stemming out of it been correctly apprised by the General Staff at Army Headquarters and correlated to NEFA [North East Frontier Agency], it is possible that we would NOT have precipitated matters till we were better prepared in both theatres.' This sentence has been used by anti-India elements like Neville Maxwell to put the blame on Delhi.

The General Staff at Army Headquarters knew that any move in NEFA would have consequences in Ladakh, here the level of preparations was minimal; according to the Report: 'We acted on a militarily unsound basis of not relying on our own strength but rather on believed lack of reaction from the Chinese. We forgot the age old dictum of the 'Art of War summed up so aptly by Field Marshal Lord Roberts.'

Field Marshal Roberts had said 'The art of war teaches us to rely not on the likelihood of the enemy NOT coming, but on our own readiness to receive on the fact that we have made our position unassailable.'

But till the last minute, the government (primarily then defence minister V K Krishna Menon) believed that 'The Chinese will not dare'.

The Report continued: 'Militarily, it is unthinkable that the General Staff did not advise the Government on our weakness and inability to implement the 'Forwards Policy'. General [B M] Kaul [Chief of General Staff] on his report has brought out that, on a number of occasions in 1961-62, the Government were advised of our deficiencies in equipment, manpower, and logistic support, which would seriously prejudice our position in the event of a Chinese attack on us.'

At the same time: 'Orders were given by the General Staff in December 1961 for the implementation of the 'Forwards Policy' without the prerequisite of 'Major Bases' for restoring a military situation, as laid down by Government. Indeed General KAUL as CGS and the DMO [Director of Military Operations, Maj Gen DK Palit], time and again, ordered in furtherance of the 'Forward Policy' the establishment of individual posts, overruling protests made by Western Command.'

Winds of folly were blowing over Army Headquarters in Delhi; we know what happened a few months later, in October/November 1962.

Major Shaitan Singh and hundreds of his comrades sacrificed their lives to undo the foolishness of the politicians; the Report added: 'There might have been pressure put on by the Defence Ministry, but it was the duty of the General Staff to have pointed out the unsoundness of the 'Forwards Policy' without the means to implement it.'

Further, General Henderson pointed out: 'It is apparent that none of this planning took place and NO operation orders or instructions were issued by the General Staff. It was therefore NOT possible for Command or lower formations to issue any comprehensive order without a directive from the General staff.'

Is it the reason why the Report is still classified 60 years after the event?

One of the conclusions of the Report was: 'It was a junior leaders and jawans battle and there is no doubt that they acquitted themselves well. They fought under grave handicaps and in face of defeat; yet there was no sign of undue panic and never a rout.

'The main reason for this was that troops fought under commanders they knew and trusted. There was no interference or short-circuiting in the chain of command and commanders on the spot were given freedom of action.

'The good name of our Army was NOT completely marred in LADAKH and the grave errors committed by the General Staff to an extent mitigated, thanks to the fighting ability of our troops.'

Indeed, the 13 Kumaon and other units fought like lions. It is said that some 3,000 Chinese lost their lives in a couple of days in this sector.

Leh was probably saved by their act of heroism.

Ironically, 58 years later, Tibetan commandos captured the same peaks to have a strategic peep on the Rutok road.

In the process of the negotiations in Chushul and Moldo in the nearby Spangur Gap, the area was demilitarised in exchange of an agreement in the Fingers area on the Pangong Lake.

Without commenting on the wisdom of this political move, one can only say Kitna dukh these stunning mountains have witnessed.

While on the spot, an idea came to me, when Chinese officers come to Chushul/Moldo for LAC talks, they should be invited to visit the Rezang La Memorial to understand what the Indian soldiers are made of.

Claude Arpi is a long-time contributor to Rediff.com and you can read his earlier columns here.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com