'At some point you know there is nothing else that you can do for them. You have to just wait and watch them die.'

'At some point you know there is nothing else that you can do for them. You have to just wait and watch them die.'

'Ebola is a highly infectious disease with high mortality. The key point is not to panic.'

'I like working where there is an acute, desperate need for medical care in a vulnerable population and in emergency contexts.'

Dr Kalyani Gomathinayagam, a young Indian doctor who volunteered to spend four weeks in west Africa helping those suffering and dying of Ebola, speaks to Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com on why she took on an assignment many would shy away from.

Dr Kalyani Gomathinayagam (centre) with the Medecins Sans Frontieres team at the hospital in Foya, Liberia in their protective gear. Photograph: Martin Zinggl/MSF

While her family -- parents, sister, nephews -- was bringing in Dussehra, and later Diwali, last month in Madurai, Kalyani Gomathinayagam was one and a half continents away in Foya, a border town in central Liberia, valiantly struggling through her Ebola-affected patient load.

She was one of the few doctors, and likely the only Indian, who had volunteered to work in that region treating victims of the awful epidemic.

At the Medecins Sans Frontieres-run makeshift tent hospital, image, below, she and her colleagues -- they were three doctors and 125 medical personnel on the team -- in their cumbersome special protective gear, horribly stifling in the west African heat, were planning the daily rounds of their 100-120 patients.

The international Nobel-winning humanitarian medical organisation -- that operates without borders offering aid to casualties of disaster, war and disease -- had chosen to beef up medical facilities in Foya, in addition to capital Monrovia, because that was where the scourge started in Liberia, due to its proximity to Guinea and Sierra Leone. The 2014 west African epidemic of Ebola began in Guinea with a two-year-old boy reported to be the first case.

Burials happen as per strict procedures with the members of the family and the MSF outreach team in attendance. Photograph: Martin Zinggl/MSF

Unlike in a regular hospital in normal environment, at the Medecins Sans Frontieres outpost, which the team started up and organised, an ordinary medical routine like meeting and examining patients, once a day, is an enormous challenge when they are suffering from the deadly hemorrhagic fever brought on by the ebolavirus. No medical staff can be within the high risk areas where confirmed or suspected cases are located, for more than one hour or so, and rounds begin as early as 7 am after a careful assignment of hourly duties.

Further, Kalyani explains: “(Ebola) changes the patient-doctor dynamic. You as a doctor will not be able to see the patient face-to-face. The patient will not be able to see you much, because you are behind the protective gear. He can only hear you and see your eyes..."

Doing a proper physical examination of the Ebola afflicted, or even standard medical procedures, is simply not possible and treatment has to be worked around these obvious constraints.

“Most things you normally do for a patient could not be completed in this setting because of the restrictions of the personal protective gear. Or because of the risk involved for the staff in doing any invasive procedure. Everything had to be premeditated or discussed with the team beforehand. (You have to have) a specific objective of what you want to do when you are inside. It is not like you have a lot of time to keep on doing (anything). The weather in Liberia is very hot. Your (goggles) get very foggy and then you are not able to see or do anything useful for the patient. Everybody has to go in turns.”

Kalyani, who has seen her share of tough assignments in epidemic- and illness-prone parts of the world like Haiti (post the earthquake), Ivory Coast, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, feels that treating and aiding the Ebola affected has been her most challenging and emotionally taxing assignment till date.

Dr Kalyani with the Liberia national hospital staff. Photograph: Martin Zinggl/MSF

“There’s a feeling (of being) helpless in the face of the epidemic. Knowing (that the only thing you can do) is watch and wait to see how the patient recovers. You never know which patients are going to make it. You can (do) guesswork, but you would be surprised that some of them actually do make it and some couldn’t…"

Worse is the grim reality of being utterly powerless while facing an ambush by this ferocious epidemic. “At some point you know there is nothing else that you can do for them. You have to just wait and watch them die… Sometimes you feel helpless, like about how much you can do. If that happens five times a day you start (wondering) if you are actually doing something useful or not for the patient…”

Equally traumatic is that in the absence of family, a doctor is the only human link a frail, dying patient has in his last moments. Not getting involved is scarcely an option. “(The sense of helplessness) compounded with the effect that the family cannot be with the patient when he is actually dying, is sort of stressful for the whole team. You are trying to give a sort of support, instead of the family, and if someone doesn’t make it, that also leaves an impact on you.”

Rigorously containing the wildfire spread of Ebola is the only way to prevent the deadly disease from winning. It is crucial that the patient is isolated from his relatives. His family can only spend snatches of time with the patient even if he is dying.

Kalyani is no stranger to practising medicine in rough situations. After her medical training in Madurai, and working in rural Kerala, she opted to spend a decade working as a medical officer with the Indo-Tibetan Border Police at extremely isolated regions on the border, including remote places in Jammu and Kashmir, Arunachal Pradesh, as well as a stint, once, on the Kailas-Mansarovar yatra route at Kunji Post.

A posting with the United Nations Peacekeeping Force took her to the Democratic Republic of Congo. “I like working where there is an acute, desperate need for medical care in a vulnerable population and in emergency contexts. It gives me tremendous satisfaction to reach out to people who are in dire need of medical attention. Professionally I find it challenging to work in such complex emergencies in resource limited settings.”

She chose to join Medecins Sans Frontieres after her assignment in Congo because she liked the way they handled medical emergencies and their work philosophy. “I saw them being actually hands on with medical care -- when it was actually needed -- for the most vulnerable population.”

Why did Kalyani so courageously opt to take care of the Ebola affected at risk to her own life? Why was opting to treat the Ebola-affected, though chancy, not at all out of the realm of mission impossible for her? “Liberia was like any other acute medical emergency we normally respond to. It was a bit risky and we had to be briefed thoroughly about the protocol before we actually went to the field. They asked me if I would like to go for an Ebola project and I said: Why not?"

She says the risks didn’t worry her excessively. Medecins Sans Frontieres is always very scrupulous and transparent in the manner in which they brief their teams about the risks involved before seeking volunteers; no one is forcibly assigned anywhere. And Kalyani felt that their stringent safety procedures would keep her from harm. “We had protocols. We had personal protection equipment. Of course, you are a little bit concerned. If you have a little bit of body pain you start wondering… I felt very safe and comfortable. Sometimes you know what you are facing. Sometimes you don’t know what you are facing… But it was the confidence I had in my organisation that they would also take care of me if something happens. If I want to do something useful I (weigh it), I take adequate protection and I go for it.”

Naoufel, part of the MSF team, hands out water sachets to new arrivals at the MSF hospital in Foya, Liberia. Photograph: Martin Zinggl/MSF

That was not necessarily how her family back in Madurai saw it. While they are accustomed to Kalyani heading into the unknown to treat the uncared for, naturally it makes them edgy too. She makes it a point to be in touch daily with her folks on the telephone so they are comfortable.

“Of course, the family will get concerned when you are going for such a risky project. They also understand I could do something for the patients who are dying there… They would worry irrespective of what I try to explain… If people don’t see how safe the MSF environment, in which we are working, is, they will not understand…” Kalyani strives for some balance by alternating risky medical missions with time spent at home with her family.

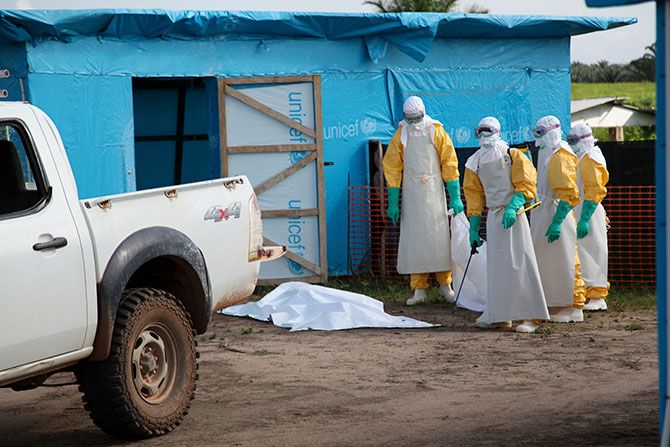

National health workers in protective gear, at an isolation unit in Foya district, Liberia. Photograph: Ahmed Jallanzo/UNICEF/Handout via Reuters

After her briefing in Geneva, Kalyani could have been assigned to either Liberia, Guinea or Sierra Leone, but was assigned to spend four weeks plus in Foya, through September and part of October, and then a three-week health monitoring after the assignment, in Geneva. She says she would “definitely” like to go back and help further in the war on Ebola should she get another assignment because she feels her newly-gained experience is valuable.

The 21 days she spent in Foya were a disturbing, numbing period, when her focus was only on fighting the epidemic and the plight of her patients. But she was also able to come away from Liberia with a few impressions. “A majority of Liberians are devout Christians. When you greet them and ask: ‘How are you?’… even to a stranger, the reply would be ‘ Thank god’. This was even with my seriously ill patients. It speaks of their faith in their god in all circumstances... The hard work and dedication of the national staff, who were (concerned) seeing their communities get affected by this disease, inspired me to do more from my side as well.”

She also realised that India has far more resources than west Africa does for conquering disease. “We respond to any situation very quickly (by comparison)… We are very high in human resources in the medical field.”

On this trip and the earlier periods of time working in Africa, Kalyani has discovered a few things: “I admire the strength, courage and tolerance the Africans possess. I sometimes envy their easy smiles even in the face of dire circumstances and their inherent (ability in) finding something amusing. (I also admire) their commitment to family, which means a whole extended family; they share everything with them.

“Be we Indian or European or American, we are all Muzungu (people of European descent/aimless wanderers) to them, but it is amazing how the charms of Bollywood have reached even the remotest village in Africa. When I say I am from India, they connect me with the movies of Amitabh Bachchan, Rajesh Khanna, Hema Malini, Zeenat Aman...”

World news headlines have been dominated by the spread of Ebola and its casualties. Often the headlines are unduly alarming. Few know that Ebola is concentrated mainly in one area of Africa at this time. Kalyani offers the ground reality: “Ebola is a highly infectious disease with high mortality. The key point is not to panic. We have to respect Ebola because the mortality is very high. But there are also ways to contain it.”

West Africa has been plagued by a series of Ebola epidemics before, starting 1991, where MSF helped out as well, with incidences being as high as 500 or so, she explains. Undoubtedly this round has been the worst. “In this epidemic, from almost March to October, we have almost crossed the 13,000 case mark. That means the epidemic was clearly out of control.”

The reason for the explosion in cases, this time, is not clearly known except that a proper response was not in place to prevent rapid transfer of the virus. The key, Kalyani says, as per how global medical organisations fight the disease, is to stop the chain of transmission and offer a coordinated or synchronised global response.

“The most heartening news is that for the past one month they have not recorded any new case coming from Foya. There are some cases in the periphery -- in other districts. On the whole I think the community has really participated a lot in bringing the epidemic under control in Foya. That’s a good sign.”