'The Himalayan people may not represent a large or politically influential section of the population, but India's security depends on them.'

'Let us hope Sikkim remains a beacon of stability,' says Claude Arpi after a recent visit to the picturesque north eastern state.

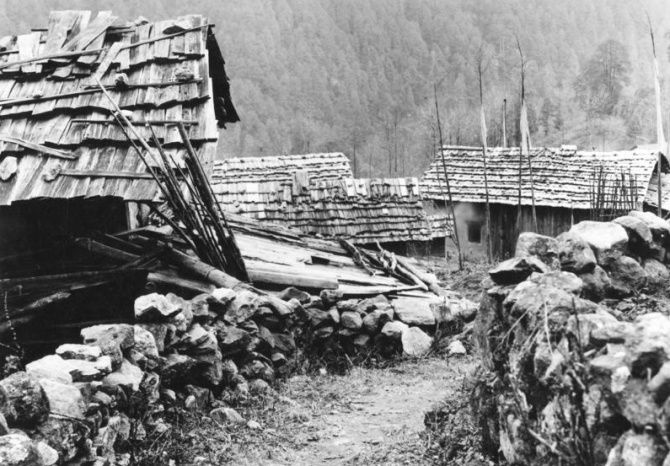

A hundred years ago, a young French lady described thus her visit to North Sikkim: 'Perched on a mountain slope, a humble monastery dominates the villagers dwellings. I visited it the day after my arrival, but finding nothing of interest in the temple, I was about to leave when a shadow darkened the luminous space of the wide-open door: a lama stood on the threshold.'

The narration continued: 'I say 'a lama', but the man did not wear the regular monastic garb, neither was he dressed as a layman. His costume consisted of a white skirt down to his feet, a garnet-coloured waistcoat, Chinese in shape, and through the wide armholes, the voluminous sleeves of a yellow shirt were seen. A rosary made of some grey substance and coral beads hung around his neck, his pierced ears were adorned with large gold rings studded with turquoises and his long, thick, braided hair touched his heels.'

When Alexandra David-Neel wrote the above lines, she had just met her future guru, the Gomchen of Lachen: 'This strange person looked at me without speaking, and as at that time I knew but little of the Tibetan language, I did not dare to begin a conversation. I only saluted him and went out.'

When she returned to the traveller's bungalow, she asked: 'Who was this lama?'

One of her attendants told her: 'He is a great gomchen (great meditator). He has spent years alone, in a cave high up in the mountains. Demons obey him and he works miracles. They say he can kill men at a distance and fly through the air.'

A couple of years after this encounter, Alexandra David-Neel decided to live for three years (between 1913 and 1916) in total seclusion at an altitude above 10,000 feet to learn the esoteric form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet and the Himalayas.

The French lady a few years later would be the first foreign woman to reach Lhasa.

The next 50 years of her life would be consecrated to tell the world, particularly in her bestseller, With Mystics and Magicians in Tibet what she learnt from the Gomchen of Lachen.

A century later, the 'magic' Alexandra David-Neel encountered continues to permeate the mountainous state.

The Beauties of North Sikkim

Alexandra David-Neel's three-year tough apprenticeship was on my mind when I arrived in Sikkim; for me, a visit to North Sikkim was a must.

The two main villages are Lachung and Lachen.

Lachung, the 'small pass', is in fact higher in altitude than Lachen (2,900 metres above sea level versus 2,750m); it is a large and prosperous village.

If one continues (the next day) to the north is Yumthang, the 'Valley of Flowers', with its myriad rhododendrons of different colours and beyond at 'Zero Point', one experiences the snow-covered Tibetan plateau at some 15,300 feet.

Further north is a 'restricted' area under the control of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police and the Indian Army.

Incidentally, it is the only area where the boundary with China is emborned with a series of cairns (it is unfortunately not the case in southern Sikkim, an area which witnessed a standoff for 73 days with China last year).

In order to preserve the pristine natural beauty of these northern reaches, plastic bottles are banned. If you are caught with a bottle of mineral water, there is a fine of Rs 2,000.

Lachen, the 'big pass', though built in an extremely narrow valley, has developed at a fast pace in recent years.

I could not visit the Gomchen's cave due to the bad road between Lachen and the village of Thangdu where his abode was located. Hopefully, this will be remedied soon.

Towards the north is the lake of Gurudongmar.

Legend says Guru Rinpoche (also known as Guru Padmasambhava) dwelt in seven sacred and hidden lands; most of these places are in Tibet and Bhutan, but locals believe that Guru Rinpoche visited Sikkim in the 8th century, he then blessed this often-frozen lake near the Tibetan border, which became 'Gurudongmar Tso', the 'lake of the red-face Guru'.

Some say the Great Guru manifested at the lake in the form of Gurudongmar or Gurudrakpo, one of the main aspects that the tantric master to establish Buddhism in Tibet and the Himalayan region.

Gurudramar, the red-face deity of Guru Rinpoche, is one of the main protecting deities of several important monasteries in Sikkim, including in Lachen and Pemayangtse; in the 13th century, the ancestors of Sikkim's ruling Namgyal dynasty were instructed by the deity to go southwards to 'Payul Demjong', the 'hidden valley of grains', as Sikkim was traditionally known. A visit to Gurudongmar, three hours from Lachen by road is a must.

Something else touched me when I reached Gangtok: Sikkim is clean and the environment is well-protected. This is particularly striking when one comes from a state where plastic and garbage litters each and every public place; it is a truly refreshing experience to see clean forests, streams and villages.

Driving in from West Bengal, Sikkim seems paradise.

Sikkim is indeed a stable and prosperous State; the fact that the charismatic Chief Minister Pawan Chamling has recently become the longest serving Indian chief minister, is a clear sign of the continuity.

Sikkim is also the first Organic State in India, showing the way to other smaller progressive states.

At a time this state is so crucial to India's security, it remains a trend setter and a model. India can't afford to have insecure and 'unhappy' borders, when the northern neighbour is always ready to change the status quo.

Another welcome change is the forthcoming disenclavement of the state. A couple of weeks ago, Pakyong airport formally obtained a license to operate commercial flights, thus enabling Sikkim to be connected with the rest of the country by air.

Union Aviation Minister Suresh Prabhu tweeted: 'The PakyongAirport at Sikkim got a license today for scheduled operations. It's an engineering marvel at a height of more than 4,500 ft in a tough terrain.'

The need of the hour is the strengthening of the Indian Himalayan border states; the issue has even become more urgent after the Doklam episode.

Sikkim could be a role model for other states.

Another must visit is Nathu-la, the border pass between India and China; it is a special place for many reasons.

Several times a year, it witnesses BPMs (Border Personnel Meetings) between the Indian and Chinese armies in a 'hut' built for the purpose. It symbolises the decision taken at the highest level of the Indian and Chinese States to solve the border issues around a table.

Nathu-la is also the entry point for the Kailash Yatra organised every year by the ministry of external affairs (it was unfortunately cancelled in 2017 due to the Doklam episode). Several batches of Indian pilgrims will go again on pilgrimage to the holy mountain this year.

Nathu-la is also one point where the Sikkimese and Tibetan traders meet during several months. Pre-Doklam, the border exchanges had reached a peak; more than Rs 80 crores (Rs 800 million) for the financial year; it is hoped that business will reach new heights in 2018.

Traditionally (till 1962), it is via Nathu-la (and also Jelep-la further south) that most of the trade with Tibet was conducted.

A strange episode came back to mind: In the early 1950s. India started feeding the Chinese troops who had just started occupying the plateau.

John Lall, a former diwan of Sikkim, was posted in Gangtok when the supply of rice took place; he could witness the long caravan of mules leaving in the direction of Nathu-la.

'This could, and indeed should, have been made the occasion for a settlement of the major problems with China as a prelude to the altogether unprecedented help requested from the Government of India,' Lall remembered. 'It simply did not occur to anyone in Delhi, and which caution as I advised was brushed aside.'

The mules of yesterday have been replaced by the long convoy of Indian tourists wanting selfies near the BPM hut.

Ultimately, Sikkim needs to remain stable'.

One possibility is 'development', particularly eco-tourism which can bring rich dividends. But it is probably not enough. It is also necessary to empower the local populations.

China has recently decided to 'empower' the Tibetan populations living on the border; Xi Jinping's 'border' doctrine is: 'govern the nation by governing the borders, govern the borders by first stabilising Tibet, ensure social harmony and stability in Tibet, and strengthen the development of border regions.'

China tries to kill two birds at the same time; it uses border tourism as a way to tackle poverty ...and to protect the country's borders (by buying the local population over to China's side).

With the fast developments taking place on India's borders and the arrival of a railway line in Yatung in the Chumbi Valley, the pressure is going to greatly increase for the local population to remain steadfast.

The Himalayan people may not represent a large or politically influential section of the population, but India's security depends on them.

Let us hope that Sikkim can remain a beacon of stability and cleanliness.

Incidentally, there is hardly any crime against women in Sikkim, another sign of a progressive society.