Mr T V R Shenoy, who contributed columns to Rediff.com from its birth, passed into the ages on Tuesday evening.

As we grieve and mourn his passing, Ambassador M K Bhadrakumar bids adieu to an unusual human being, a sage for our times.

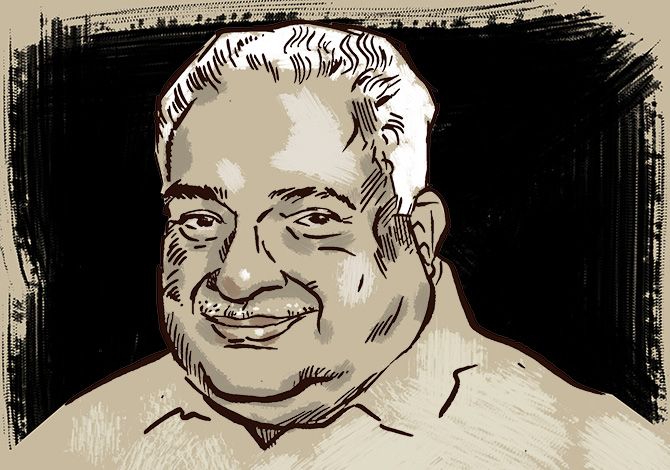

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

When I woke up this morning and was making my coffee, my wife walked up to break the news as calmly and gently as possible -- lest my heart broke all of a sudden -- that T V R Shenoy is no more.

She apologised that she knew the previous night, but just didn't have the presence of mind to tell me as she sat beside me watching me have supper alone, lost in thought.

Srilata was right. Shenoy was more like a brother to me than a friend. I feel devastated.

I first met Shenoy in the winter of 1972 when I came to Delhi for my interview with the Union Public Service Commission for the civil services examination.

Since that was the first time I was travelling alone out of Kerala, my uncle suggested that I could put up in the Delhi office of his newspaper Kerala Kaumudi in the INS Building on Rafi Marg.

So, I was in the ante-room of the office, acclimatising myself to the North Indian winter milieu, when I first came across Shenoy, who was the bureau chief of Malayala Manorama, whose office happened to be next-door.

Shenoy was a staunch 'anti-Communist' from his Maharaja's College days in Cochin, weaned in the politics of the Kerala Students Union (affiliated with the Congress party). But, typically, he'd held my father in high esteem as a humanist and man of letters (despite being a Communist.)

Shenoy was aghast that I didn't have any coaching for the civil service examination. (Trivandrum was a mofussil town in the late 1960s.) So he insisted on giving me a few 'mock' interviews to draw me out and get me to articulate with less diffidence.

Those were the days of the teleprinter and Shenoy had to file his copy by early evening to Kottayam. Soon after finishing his day's work, Shenoy would walk over to Kerala Kaumudi and spend a couple of hours with me. He didn't have to do that.

Exactly two decades later, when he was my guest in the embassy compound in Islamabad during my posting in Pakistan, I asked Shenoy one memorable evening etched in memory still, over a glass of his favorite single malt Scotch whiskey Glenfiddich, why he took such an instinctive liking toward me.

He fell silent.

And then, with eyes slowly turning misty -- it may surprise many that this man (who would help L K Advani build bridges with Kanshi Ram; would persuade Jayalalithaa to have truck with the BJP; and was a close personal friend of Dhirubhai Ambani) was deep down highly emotional, sensitive and highly vulnerable himself in human relationships -- Shenoy began explaining in a wistful tone that he saw something of himself in me dating back to his own first arrival in Delhi to take up job as a journalist -- a shy, introverted boy, precociously intellectual and eager for knowledge, but with all the social handicaps of a lower middle class family background and a life of privations spent in the backwaters of India in the 1960s -- an innocent abroad; raring to conquer, nonetheless.

In the event, Shenoy's mock interviews had a magical effect on me. The UPSC interview turned out to be a cakewalk.

Lesson number one from Shenoy: I should have a healthy contempt toward the interview board because it almost always comprised men with inferior intellect. (Indeed, I retorted to an erstwhile ICS and a secretary to the external affairs ministry who asked me to sing a song from the film My Fair Lady, following a long, stimulating discussion about Henry Kissinger's path-breaking visit to China.)

At any rate, the interview lasted for over an hour, much longer than usual, and when I reported back to Shenoy, he comforted that it didn't really matter since I was only 21 years old and that was my first attempt.

When it transpired later that I'd topped the list of interviewees, Shenoy was thrilled beyond words.

Thus was born a beautiful friendship.

It was a mark of the profundity of our friendship that we really didn't mind that we were poles apart in our political beliefs.

Of course, I knew he had links with the RSS and even played a role in persuading Advani to acquiesce with the rise of Narendra D Modi in that fateful autumn of 2013.

But then, I saw Shenoy always, first and foremost as a humanist, extremely erudite (owning a fabulous library of books cramming all space in his apartment, tucked away even under his bed) and with that rare capacity to enjoy the simple pleasures of life -- a transparent friendship, for example.

When posted abroad and visiting India on home leave, all I ever needed was one drinking session with Shenoy to catch up on all that ever happened in my country when I was abroad.

His eyes escaped nothing -- a shrewd observer who could distinguish from a mile away the grain from the chaff with a single glance.

Shenoy also played a big role when I walked out of the Indian Foreign Service, abruptly turning my back on the impending presentation of credentials to Saddam Hussein in Baghdad on August 8, 2001.

When I came to Delhi to push my case for resignation, Shenoy rushed to see me in the external affairs ministry hostel. He was just turning 60.

We had a very long, exacting conversation where he tried hard -- with manifest despair -- to dissuade me from quitting the diplomatic service. (I had still 10 years left in government before retirement.)

He invoked all the reasoning power in his repertoire. But I explained that I was quitting my immensely enjoyable profession and a life of high intellectuality and seamless opportunities of self-enrichment as a diplomat, because I was sick and tired of bureaucracy, its shenanigans and skullduggery -- and, indeed, the backstabbing and the notorious lack of camaraderie among colleagues that was endemic to life in the foreign service.

Shenoy listened with rapt attention and agreed, finally, merely saying, 'Bhadran, your father would have approved what you are doing.'

Shenoy had extensive contacts with the bureaucracy, but had a sneering contempt toward bureaucrats as a breed.

Indeed, the man abhorred the very thought of 'insititutionalizing' himself in any capacity. To my mind, a membership of the Rajya Sabha or a ministership in the Union Cabinet was well within his reach.

Power, prestige, privilege, perks -- these phoney notions never occurred to Shenoy's scheme of things.

Shenoy brings to mind the protagonist in the English poet Shelley's immportal Ode To a Skylark: Higher still and higher

From the earth thou springest

Like a cloud of fire;

The blue deep thou wingest,

And singing still dost soar, and soaring ever singest.

In the golden lighting of the sunken sun last evening, he rose like a blithe spirit, like a star in heaven -- 'like an unbodied joy whose race is just begun'.

- Readers can savour Mr Shenoy's columns here.