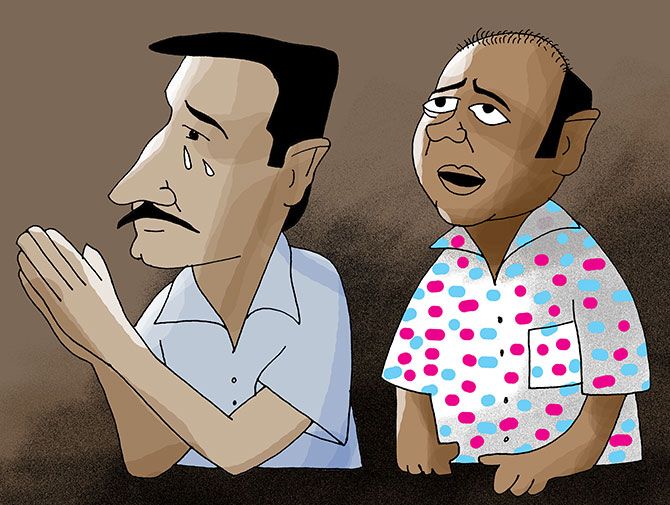

Shyamvar Pinturam Rai and Pradeep Waghmare.

Both erstwhile employees of Peter and Indrani Mukerjea.

In the witness stand on Monday, Waghmare came across as a cheerful, straightforward man who is attempting to clamber his way towards prosperity.

In the witness stand on Friday, Rai shed his customary jauntiness and broke down weeping, begging forgiveness from CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale.

Vaihayasi Pande Daniel reports from the Sheena Bora murder trial.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh /Rediff.com

Two friends took the witness stand in CBI Special Courtroom 51 at the Mumbai city civil and sessions court, south Mumbai, back to back, at successive hearings in the Sheena Bora murder trial, between Friday, June 15 and Monday, June 18.

They could not have been more different.

Nor their lives.

One, who hails from Danwa, Madhya Pradesh, was a driver and an odd jobs man, who confessed to murder and has been languishing in jail for the past three years in Thane, outside Mumbai.

The second, who hails from Pune, Maharashtra, was a cleaner and also an odd jobs man, who became a poultry farmer, now makes cheese popcorn for a living, in Badlapur, outside Mumbai, in Thane district.

Their life paths intersected and ran parallel for a good ten years till 2015 and then rapidly and wildly diverged 180 degrees after that.

Shyamvar Pinturam Rai and Pradeep Waghmare.

Both erstwhile employees of Peter and Indrani Mukerjea, who once ran INX Media Services Pvt Ltd.

In the witness stand on Monday, like earlier hearings, Waghmare came across as a cheerful, straightforward man who is attempting to clamber his way towards prosperity.

In the witness stand on Friday, unlike earlier hearings, Rai, whose future is unknown, shed his customary jauntiness momentarily and broke down weeping, begging forgiveness from CBI Special Judge Jayendra Chandrasen Jagdale.

On Friday morning Rai was brought from Thane jail dot on time at 11.30. Judge Jagdale had asked for him to be produced after he filed a request for bail already 70 days ago.

Wearing a grey shirt, khaki pants and sandals, Rai was waiting in the corridor outside Courtroom 51, with three policemen, as a lengthy Punjab National Bank scam bail hearing laboriously progressed.

Special CBI Prosecutors Kavita Patil and Bharat Badami had also not arrived,

The corridor was reasonably quiet.

The smell of mildly stale hot oil, used for frying pakodas or wadas too many times over, courtesy the court canteen, hung in the air.

On this clammy, hot day, in spite of the recent but stuttering, sputtering arrival of the southwest monsoon, nothing was more gladdening or precious than that occasional waft of cool breeze, that somehow wound its way into the corridors, reminding one how very simple the pleasures of life can be.

The stillness was periodically broken by the drill and hammer of the renovation construction workers.

By the dull, unstoppable drone of the lawyer for the PNB accused.

By the voices of two squabbling lawyers.

By the grumble of prison trucks arriving below.

By the shuffle and drag of passing feet.

By the racket of the lift's artificial voice ordering each of its charges to 'Please close the door!'

And by the occasional mumble of conversation between policemen or lawyers or relatives as they drifted past.

Then the sweet sound of a young child's voice could be heard far off and it grew closer.

Rai's wife Sharda, son Ashish, 3 and daughter Shraddha, about 11, came trotting down the corridor from the far end, waving at him, and sat down on a bench, ten feet away from the former driver.

Both children craned their necks to look at "Papa" and he looked at them longingly.

Finally, with his police escort trailing him, Rai could not hold himself back any longer, and came to talk, standing across the corridor from them, speaking stiltedly initially.

His wife, dressed in a green kurta-salwar and a pink chunni, sat wooden-faced, not speaking to him. She, who had been recently bereaved, said she had nothing to speak to him about.

After a bit Rai went back to his earlier seat in the corridor, closer to the judge's chamber.

Ashish and Shraddha, both remarkably well-behaved children, kept eyeing their father.

Every so often, Ashish, an adorable-looking child, with slanted upturned coal black eyes, clad in a blue checked shirt, shorts and sandals, would rocket down the corridor, on little pattering feet, to his dad, spend a few precious minutes with Rai, and rocket back to his mom.

He repeated his wee journey four or five times. His sister, in a blue frock, serious, and mature for her age, watched the tableaux intently.

Briefly, those dark, dank corridors were bathed in the eternal sunshine of spotless little minds, making it a better place.

Rai was not summoned into the courtroom till after lunch. During the lunch break Sharda and children came across to sit with Rai. She had no meal for him as she had not been allowed to bring the food she made in by the guards strangely.

Finally, she went down and got some pav and snacks.

The driver was called in past 3 pm. Sharda and the kids filed hopefully into the rear of the courtroom.

Rai took the stand, barefoot, his face crumpling, he immediately began to sob, tears bathing his cheeks: "Humara parivar mushkil mein hai. Koi madad karne ke liye nahin hai. Ghar kiraya ka hai (My family is in trouble. There is no one to help them. The house is on rent)."

He went on mournfully that there was no one to support his family adequately and his wife was finding it increasingly difficult to cope.

Sharda watched him, from her seat, dry-eyed, her face stiff.

His daughter Shradda listened somberly too. Ashish, who seemed not to notice that his father was crying, had turned around in his seat and was facing backwards.

The judge gently told Rai: "Ha yeh case mein gavai diya hai. Influential log hai. Aapka jaan khatra mein hai (Yes, you have given your testimony. They are influential people. Your life is in danger)."

Rai said he would stay at home and not leave the house.

"Bahar nahin nikloonga (I won't go out)."

Judge Jagdale: "Phir bojh aapki patni ko aayega (Then the burden will remain with your wife)."

Rai went on, weeping and speaking frantically, "Kamayenge. Naukri karenge. Bachhe ko palenge. Bachhe ko sadhan nahin hai padhai ke liye. Sasur mar gaye. Patni ko takleef hai (I will earn. Do a job. Take care of my children. They have no means to study. My father-in-law has died. My wife is a great deal of difficulty)."

Folding his hands in front of his face, in desperation, tears streaming, he begged: "Kshama mangta hoon (I ask for forgiveness)."

Rai also complained, holding his hand over his left ear: "Jail mein, kaan mein sooo-sooo aavaz aa raha hai. Aakh mein takleef hai. Dikhay nahin de raha hai (In jail, I keep hearing a sooo-sooo sound in my ear. I have a problem with my eyes. I am not being able to see properly)."

The judge assured Rai that he would pass an order to have his medical issues investigated. He looked to Patil for her take.

Patil promised to check on the legal aspects of granting an approver bail while the trial was still in process. And if there were any exceptions possible.

"I will check the legal position," Patil concluded. The CBI lawyer also agreed to reply to his bail application as soon as possible although she attributed no reason to the delay.

The yawning gap in the room between Rai's hopes and expectations and the actual reality of his plight presented itself awkwardly and uneasily.

He felt, for some misguided reason, his act of turning approver and giving testimony against the rest of the accused had magically set things right and wiped his slate clean. No one wanted to set him right on that score or disappoint him.

Rai and family left.

Judge Jagdale took off his glasses and mopped his face with a handkerchief, looking, it seemed, a trifle sad or momentarily worn out.

The judge, ever since he took on this case, one has noticed, more than others on the case, reserves his gentlest tones in the courtroom, for the most deprived.

Rai stood downstairs in the courtyard speaking to his wife for a long time, then he left for prison, without a backward glance or wave. Sharda, with her children, trudged away.

Monday was the final day for Waghmare's cross examination.

He had worked as a cleaner in both the INX Thane office and the Mukerjeas' home, Marlow, Worli, south central Mumbai.

Niranjan Mundargi, lawyer for Accused No 2 and Indrani's former husband Sanjeev Khanna, had sent word that he had no requirement to separately cross examine Waghmare.

Shrikant Shivade, Peter Mukherjea's trial lawyer who has represented actor Salman Khan, editor Tarun Tejpal and other notables, began his cross examination after 12.30 pm and continued post-lunch.

Waghmare was wearing, on Monday, a bright blue, white and pink checked shirt, grey pants, a new haircut and his usual candour.

The judge asked curiously and kindly if he had come alone. He said he had not and that his wife was there.

Rohini Waghmare, in black and white, was sitting in the second row of the court.

After the last hearing, the monsoon had truly begun and on Monday the court building was cool and breezy. But summer had not yet left Courtroom 51, which was still suffocating because of the closed windows and the still heated-up metal rows of trunks.

Shivade first made some enquiries about Waghmare's finances and ambitions, carefully building up a motive for the Mukerjeas' long-time help to have turned against them.

Waghmare, as established earlier, had been working for the Mukerjeas for many years. So had his wife Rohini, on weekdays, from 9 am to 6 pm.

The couple had nurtured dreams of starting a business. Waghmare calculated he would need Rs 600,000 or Rs 700,000 to invest in a poultry farm. He said he had not asked anyone for such funding.

He had asked Indrani for a loan of Rs 20,000 for his children's education and not received it. He has a seven-year-old son and a 13-year-old daughter who he admitted in private schools.

He left the Mukerjeas' employ in 2015 not, he categorically denied, as Shivade suggested, because he was "enraged" at not receiving the loan of Rs 20,000.

After leaving his job with the Mukerjeas, he said he took a loan of Rs 1.2 million (Rs 12 lakhs) from a bank to start a poultry farm, which he began in 2017. He spoke in Marathi to the court as did Shivade.

The farm, Waghmare explained later to me, was located near Pune and had 5,000 chickens. But it was no longer operational and instead he and his wife made popcorn in a machine they had at home, packaged it and despatched it to the Mumbai market.

After news of Indrani's arrest broke in 2015, Waghmare told the court he had received a call to come to the police station.

"I was called to the police station on the same day they recorded my statement. I had no idea why I was being called."

"I was scared," he recalled. "I reached the police station at about 11 am. There were 3 or 4 people there."

"I asked the police why they had called me. They asked if I was aware of Sheena Bora's murder. I came to know that Sheena Bora had been killed by her mother on the news."

Shivade probed what facts Waghmare felt obliged to tell the police and if the police had asked why he had left the Mukerjeas' employment. And if Waghmare had read his statement to the police carefully, word by word, before signing it.

Waghmare confirmed he had.

Shivade emphasised: "Then why did you say in your statement to the police that you had left the job with the Mukerjeas because you got angry when Indrani did not give you a loan of Rs 20,000."

His 2015 statement was shown to him by the clerks and the portion where it gave his reason for leaving was pointed out.

Waghmare appeared confused and baffled.

"The statement was written as per what I told the police. The portion marked C is wrongly written. My statement was read back to me. But it was not explained to me."

Shivade followed up with a set of questions to Waghmare about his calls to Rai and his location on various days in April 2012.

Exaggeratedly soft-spoken and neat, exact in his style of questioning, Shivade has a particularly calculated, meticulous approach, often moving his elegant hands delicately, his fingers drawing tiny circles on his palms before travelling off into the air gracefully.

There is nothing messy or by the seat of the pants about Shivade either in his demeanour or appearance.

One feels like one is sitting in a mathematics/geometry lecture rather than a court room.

The lawyer then asked about the location of the land-line phones in the Mukerjea home, their colour and their construct and gradually inched towards the most crucial query of his cross examination: The phone call Waghmare received from Peter on April 25, the day after Sheena's alleged murder.

Shivade: "Was it a push button phone or a rotary dial one?"

Waghmare: "Push button."

Judge Jagdale laughing: "Rotary phones are now in the archives!"

Shivade: "Did you have a conversation with Peter Sir on the landline?"

Waghmare: "Ho (Yes)."

Shivade: "Did you call him?"

Waghmare: "Nahi (No)."

Shivade: "Whatever conversation you had with Peter, which you deposed in court, did you record word for word, in your statement to the police?"

Waghmare nodded.

Shivade: "Did they read the statement back to you?"

Wagmare agreed.

Shivade: But (this sentence that Peter said to you that day) "Madam ne Sheena ko Rahul se chhura diya. Jaane do. Koi baat nahin (Madam has freed Sheena from Rahul's clutches. Let it be. No matter)" is not in your statement to the police?"

Patil insisted: "The words are there."

Shivade reprimanding Patil, regally: "Don't explain to the witness. Gives a totally different meaning."

Judge Jagdale offered, smiling: "At this juncture the judge cannot decide..."

Patil: "The wording is slightly different."

Ignoring Patil, Shivade questioned Waghmare why the wording was different.

Waghmare: "I have read my statement and it says the same thing."

Shivade snarled suddenly: "Chhuraya shabd dikh raha hai? (Is the word freed showing there?)"

Badami, shocked, emitted a strange expression of appeasement and astonishment: "Hurooo, hurooo, hurooo, hurooo!"

Judge Jagdale ordered: "Advocate Shivade calm down. These people are from the lower strata of society and cannot understand. You cannot treat them in this shabby manner."

An argument ensued about the legalities of the differences between these parts of Waghmare's statement in court and his statement to the police and if those stand-out sentences were an omission, contradiction or an improvement.

Shivade moved the argument into a much more rarefied legal province and the fine points of law were in debate between him and the judge.

In his initial statement to the police Waghmare worded the contents of the call from Peter differently.

He said Peter said: "Madam Rahul ko Sheena se alag karvaya. Rahul gussa mein hai (Madam has separated Rahul from Sheena. Rahul is angry)."

The difference in the use of words between both statements was mild.

The implications were much larger, and beyond Waghmare's understanding.

"Chhuraya" suggested that Indrani was keen to free Sheena from Rahul. While "alag karaya" was a more democratic interpretation of separating the couple.

Shivade might have been seen to be splitting hairs. But it was actually probably an elaborate exercise in showing up the lack of reliability of the witness and helping his client.

At this high-adrenaline point in the cross examination, Shivade suddenly excused himself and said he would be back because he had to check in on another matter happening at the high court, one block away.

He promised to be back in half an hour, by 4 pm.

Shivade was not back at 4. Or even at 5 as promised by his colleagues. He was delayed by a hearing in the Lieutenant Colonel Shrikant Purohit case relating to the 2008 Malegaon blasts.

Judge Jagdale started getting restive and irritable. He asked Shivade's colleagues for updates.

Badami stood up to ask if Shivade's abrupt disappearance from the court was irresponsible: "Is it justifiable is the million dollar question?! My witness is a very poor person. He cannot keep coming!"

Judge Jagdale assured him: "Today is the last time he (Waghmare) has to come."

Anup Pandey, Shivade's associate, promised again that Shivade would be back at 5 to close the matter.

Judge Jagdale vowed, half serious, half joking: "Otherwise, I am going to close the matter for him."

Shivade returned closer to 5.20 and apologised elaborately, with the grace of a royal courtier to the judge and to Badami.

After once again rehashing Waghmare's narration of Peter's call to him, he closed the matter asking a few queries about why Waghmare had not gone to clean the Mukerjea residence between April 23 and 25, 2012.

Shivade contended that Waghmare in his statement to the CBI had said Flat 19 in Marlow, where the Mukerjeas lived, was on rent, when actually Flat 18 was on rent.

Indrani, wearing a white shirt and brown slacks on Monday, who had been in deep consultation with Peter for a large part of the hearing, perked up at this point, standing up to listen attentively.

Sanjeev, who is mostly barely visible these days, because of the stacks of trunks, was lost in his own world.

Badami said firmly: "Human error."

Shivade insisted. "Why did you tell the CBI that Flat 19 was on rent?"

Waghmare said he didn't know why he said that.

Shivade: "Could it be that Kajal Sharma (Indrani's former secretary) told you not to go to clean on April 23 and 24th because the flat was on rent?"

Waghmare: "She didn't tell me that."

In conclusion, Shivade declared to Waghmare: "You never went to Marlow building on April 25. You never had a call from Peter that day. You are stating falsely that you received a call from Peter. You were under pressure from the CBI and the police. They detained you prior to recording your statement."

June 25 was scheduled as the date for the next hearing in the case and for the appearance of the new witness.

Two witnesses actually.

Joint commissioner, law and order, Deven Bharti and his junior colleague Nitin Alaknure, of Khar police station, announced Badami dramatically.

Badami and Patil organised for Waghmare, whose stint in the witness box, had come to a close, and his wife, to be dropped to the VT station by a CBI Tata Sumo.

Departures were not so pleasant upstairs when the senior police officer among the party of a dozen odd cops escorting the three accused, lost his temper with Peter, for delaying his departure by a few minutes.

"Bahut ho gaya natak (Enough of your nonsense)," he yelled in the courtroom, raising eyebrows all around because shouting or rude behaviour is not permitted in courtrooms.

Peter meekly picked up his papers and left.

- MUST READ: The Sheena Bora Murder Trial