'His Common Man, with his unforgettable bewildered look, will live on for a long time to come, as will so many of his cartoons. They captured important moments in half a century of India's political and social development that no words could.'

Rahul Singh on the R K Laxman he knew for half-a-century.

Rasipuram Krishnaswamy Laxman, who died in Pune on January 26 at the age of 93, was already something of a legend when I first met him in 1964. I had taken up my first job as a 24-year-old assistant editor at The Times of India in Bombay, as the city was then called.

Rasipuram Krishnaswamy Laxman, who died in Pune on January 26 at the age of 93, was already something of a legend when I first met him in 1964. I had taken up my first job as a 24-year-old assistant editor at The Times of India in Bombay, as the city was then called.

The editorial headquarters of the daily newspaper was located in Bombay at the time (it moved later to Delhi, but Laxman continued to base himself in Bombay as he felt -- and rightly so -- that he needed to be away from the country's political capital to be truly objective).

Laxman was then two decades older than me, almost as old as my father. Yet, he had a youthful, impish nature that made me feel quite at ease with him.

My editor-in-chief was the half-Parsi-half-Japanese N J Nanporia, who had worked for British intelligence in the Second World War and made a big reputation for himself as a journalist while analysing the 1962 Indo-China conflict.

The other heavyweights in the editorial hierarchy included Sham Lal and Girilal Jain, both of whom would become editors-in-chief of the Times. I was in awe of them, but with Laxman I could talk on a more friendly one-to-one basis.

He had a tiny cabin which was considered sacrosanct, since word had got around that he did not welcome visitors, or even like editorial colleagues, entering it. In fact, if memory serves me right, there was barely enough room for another person to either stand or sit on a chair in it.

But somehow he would often run into me in the corridor and beckon me in to gossip or discuss something or the other. Perhaps it was the 20-year difference in age that in a funny way bridged the gap between us.

There was another reason why I think I became so privileged. I recall once asking him how he got his ideas for his cartoons every day, day after day. By reading all the newspapers I can get hold of (there were no Indian news magazines then), he replied, and by talking and interacting with as many people as I can. And those people included me! Needless to say, I was flattered that a callow journalist like me could possibly spark a cartoon in his mind.

The cartoonists I have known deferred to their editors and tended to look on them as superior beings. Not Laxman. He had an arrogance about him and saw himself on a different plane than them. And, if truth be told, he actually was. It was his editors who deferred to him. He was unique among cartoonists in that respect.

There was never any question of any of his cartoons being turned down, even if the occasional one was not quite up to the mark. He produced his cartoon by the afternoon, the editor had a cursory look at it, and it appeared the next morning.

The editor had little say in the matter. In other newspapers, the cartoonist submitted his cartoon to the editor, and then waited nervously to find out if it was accepted or if he needed to make some changes.

Laxman may have got his idea for the cartoon from what he gleaned at the morning editorial conference that he invariably attended, or from what he read and observed. But what emerged was totally Laxman's.

I know of at least one cartoonist whose cartoons were virtually dictated to him by his editor. The editor provided the idea and the cartoonist simply drew it. Laxman's creations, on the other hand, were purely his own, with his unmistakable stamp on them.

There were other good cartoonists in India, alongside Laxman. I can think of two who produced wonderful work: Rajinder Puri and 'Abu' Abraham. Who can forget Abu's marvellous cartoon of President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, lying in his bathtub and signing an ordinance sent to him by Indira Gandhi, declaring the Emergency!

Both Puri and Abu had a political bite to their cartoons, that matched, sometimes even surpassed, Laxman's. But Laxman was much more consistent and his draftsmanship superior. He came close to being an artist, whereas the other two remained cartoonists.

Laxman also scored in another respect. He lacked malice (though he could be malicious when speaking about other people). There was nothing hurtful in what he drew. His criticism of his subjects was imbued with a certain warmth which came close to affection.

Look closely at his caricatures of Indira Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, and you can detect a sneaking admiration of them. He mocked, but the mockery had a generous quality to it that even got the victim smiling. Which is why politicians and ministers, whom he constantly made fun of, were grudgingly quite fond of him.

However, like all great creative people, he had his faults and foibles. He could be vain and petty. There was another marvellous cartoonist in the Times of India stable at the same time, whose genius was entirely different and who was also opposite in personality to Laxman: The loveable Mario Miranda (one could never call Laxman 'loveable').

Laxman was insanely jealous of Mario, though he had no need to be, since their cartoons did not really compete with each other. Mario's were quirky and goofy, while Laxman's were political and cerebral. Laxman made it clear that nothing of Mario's could appear in the Times of India. And what Laxman commanded was law.

So, Mario appeared in the Illustrated Weekly, Filmfare, and, later, in the Economic Times, never in the Times. The two men, both cartoonists and working in the same group, never got along. Laxman may have been more famous, but Mario was by far the more popular man, easily socialising and constantly having people at home, while Laxman rarely entertained and kept a distance from those he did not feel were his social equals.

Laxman was a bit of a snob and a dandy; Mario, a fun-loving extrovert Goan.

Laxman also fancied himself as a writer and wanted to emulate his famous writer-brother, R K Narayan. But what Laxman produced was mediocre. He once showed me something he had written that he wanted to eventually convert into a novel. I did not think much of it and told him so. He took my criticism badly.

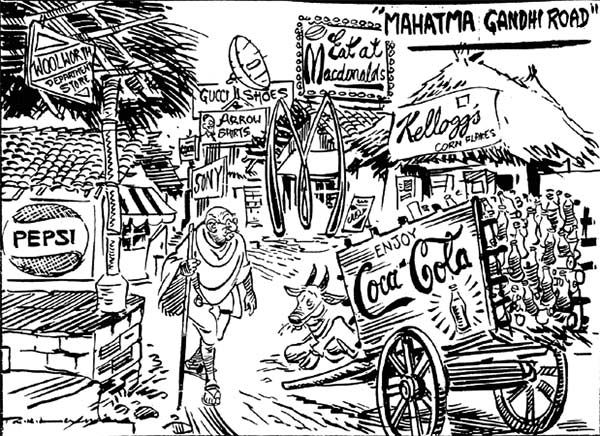

However, his idiosyncrasies pale before his outstanding cartooning. His Common Man creation, with his unforgettable bewildered look, will live on for a long time to come, as will so many of his cartoons. They captured important moments in half a century of India's political and social development that no words could.

Laxman was, very simply, the greatest cartoonist that India has ever produced and probably one of the greatest in the world.

Rahul Singh was an Assistant Editor at The Times of India and Editor of Reader's Digest and the Sunday Observer.

REDIFF RECOMMENDS