'... because he is collecting information through his app.'

'It is his responsibility to understand what data is being collected, who it is being shared with and what it is used for.'

'It is really troublesome that someone in a position of power is misleading people and presumably, citizens of the country to give up data.'

'That is not a part of informed consent.'

Ritu Jha/indica reports from California.

"How come, a prime minister who promotes Digital India, who went to Facebook, Google, (and visited other tech firms in) Silicon Valley doesn't know this much?" asks Sam Pitroda.

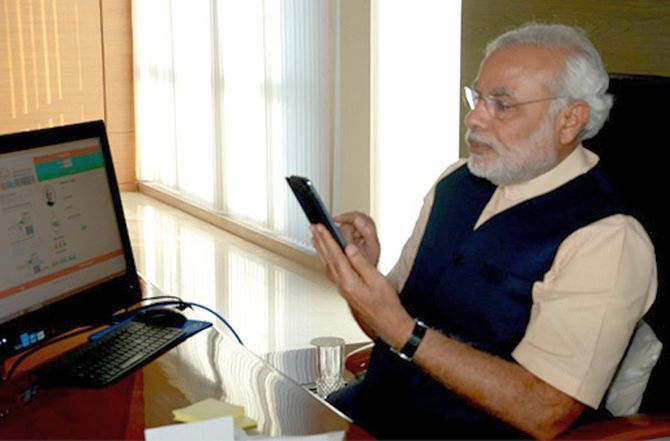

The telecom entrepreneur -- who in the 1980s was instrumental in prepping India for the digital age -- is reacting to the controversy over NaMo, Prime Minister Narendra D Modi's personal app.

Earlier this week, a French researcher using the handle 'Elliot Alderson' used Twitter to highlight privacy lapses in the app and alleged that CleverTap, a California-based mobile marketing platform, benefited from the data transfer to a third party server.

CleverTap, a US-based company, has access to data collected without consent from those who download NaMo.

Founded in 2013, CleverTap, a subsidiary of WizRocket Technologies Pvt Ltd, provides a SaaS-based user behaviour and targeting tool.

CleverTap -- which uses Amazon Web Services as its hosting provider -- has stated it does not sell, rent or re-market data.

The Bharatiya Janata Party, which Modi leads, said the app did not share data sharing with the foreign company and all that was collected was analytics to offer users the 'most contextual content'.

Modi, the first Indian prime minister to aggressively use social media, has 41.4 million Twitter followers, and about five million people using his NaMo app, launched in 2015.

Pitroda -- who is also chairman of the Overseas Congress Department of the All India Congress Committee and is an adviser to Congress President Rahul Gandhi -- gives Modi a pass on the most egregious of involvements.

"I don't expect him to have that technical expertise of this type. And it's even unfair to ask the prime minister to have that technical or data analytics expertise," says Pitroda, adding, "But his technical team should know."

Pitroda, however, says it is of concern that data was being sent out of the country, particularly data collected in the prime minister's name.

"Today if I tweet in India, (the tweet) has to first come to America. This is because we have not yet developed our social networks," Pitroda adds.

"TCS, Infosys, Wipro make billions of dollars, but would not spend even 100 million dollars developing our own product because that's risky," Pitroda points out. "They will use a product developed abroad."

"A country of 1.3 billion... has to rely on some company in California," Pitroda says, and argues for indigenously developed social media.

"When you have a market cap close to $600 billion, you can do anything you think," he says. "Social media is going to play a big role in the general election again by spreading lies, changing public opinion and by attacking people unnecessarily."

Hemant Bhargava, an expert in technology management and information technology at UC Davis, California, says the problem is not the fact that data is collected, but how it will be used.

"The Modi app doesn't say the user information is being communicated to any third party, and that is really a problem," says Bhargava.

Professor Bhargava believes such uninhibited collection of data is worrisome.

Other than in undemocratic countries like China and those in the Middle East it is unprecedented for a government to collect that kind of data.

"And here it is the prime minister," Professor Bhargava says.

"What is troublesome about the Modi app is that it doesn't say what is going to be used for," Professor Bhargava says.

"If you look at the Web page, it just says, 'Let's together script the rise of a New India'. What does that mean? There is no boundary being defined."

"Some information is captured by all apps," the professor adds. "But the problem is about consent..."

"When I allow the Uber app access to my location, I provide that permission in order to get a ride and nothing else. That is the intended purpose. But if they misuse the data... it is a problem."

He points out that the US had its own problems, allowing for physical privacy but not data privacy, as in Europe.

Many American firms, he says, were worried about global data privacy regulation because data privacy laws in Europe are much more stringent than in the US -- or in India, where it is even weaker.

"Just because something is not prohibited by law doesn't mean you shouldn't be worried about it," says Professor Bhargava.

He says he has used an app on rural electrification, a project of the Modi government. He says that app had a clear purpose -- to show the status of electrification in India's villages.

Only the use of aggregated data should be permitted, not that of individual users, he says.

Unlike Pitroda, Professor Bhargava feels Modi could not claim ignorance.

"He is still subject to the law because he is collecting information through his app," the professor says.

"It is his responsibility to understand what data is being collected, who it is being shared with and what it is used for," the professor adds.

"Regulation does not tell you what to do. Mostly business ethic governs that. In politics, and especially in a government setting with the ruling party, it is a completely different scenario," explains Professor Bhargava.

"Definitely, it is really troublesome that someone in a position of power is misleading people and presumably, citizens of the country to give up data. That is not a part of informed consent."