Olympic Silver medalist Mirabai Chani's feat is a story of grit, dedication and desire, but it isn't unique. In Manipur, discovers Vaibhav Raghunandan.

"In Manipur, if you throw a stone, it will hit a sportsperson," Renedy Singh laughs.

"Out here, everyone plays sports. And pretty competitively. Sure, there is a lot of football, but there is a lot else too," the former Indian football international says. "Why? Hmmm... brother, now you're asking the right question."

Laishangbam Anita Chanu, the woman who discovered the talent and toast of India that is Mirabai Chanu (the two are not related), perks up with an answer.

"We have a festival in Manipur, celebrated every year, called Umang Lai," she says.

"There is a sports event in every village on the day of the festival – athletics, football, khong kangjei (foot hockey)... and every kid takes part. That's where the magic begins."

This is a state that holds its culture and its mythology close to its heart, to an extent where the lines between the magic and the real, much like in a Marquez novel, become blurred.

The myth and reality of Manipur is in its sport.

Five Manipuris are part of India's contingent at the Tokyo Olympics.

Two hockey players, one judoka, and the esteemed two, whose names will not be forgotten for a time.

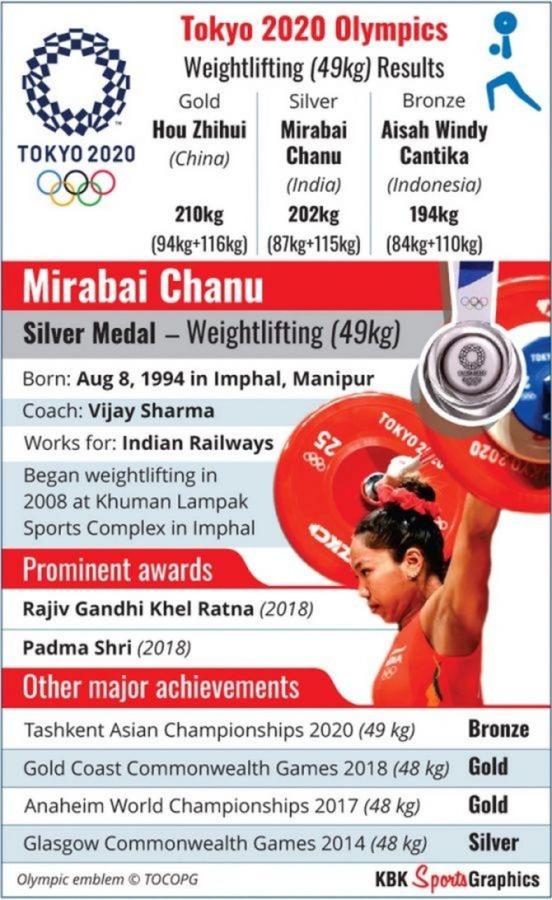

While MC Mary Kom's story has been well documented and even captured on celluloid, the latest sensation, Mirabai Chanu's is still slowly being revealed.

There were 50 kids at Anita Chanu's weightlifting academy inside the Khuman Lampak stadium in 2006, when Mirabai Chanu walked in.

She was interested in archery, but having not found any application opportunities, decided to rethink her options.

"She was 12, small, but strong. She had the look," Anita Chanu says. "So we picked her."

Every day Mirabai Chanu would travel from her village of Nongpok Kakching to Imphal on a bus, an auto or hitch a ride on a truck to get to training.

It is a story of grit, dedication and desire, but it isn't unique. In Manipur, this is the way.

This is a state that has been ravaged by separatist movements, a drug trade epidemic and regular economic blockades -- in addition to being one of the most militarised zones in the country -- over the past half century.

And yet its people have survived and thrived. They take care of their own.

"Manipuri society is divided into neighbourhoods called leikai," says L Somi Roy.

A conservationist and writer, Roy has spent the better part of the last decade working to revive traditional arts, culture and sports in Manipur.

"A leikai is a cohesive, social organisation within neighbourhoods," he says. "And I say organisation because it works in different ways. For instance, when someone dies, the cremation is taken off the hands of the bereaved family and the leikai takes over."

In a leikai, every household nominates an able-bodied person to help with community needs.

Monetary contributions are gathered through the year and used for work within the community -- often as diverse as firewood and football boots.

"Every leikai will have a sports club; it's just integrated into societal structure," Roy says.

Renedy testifies to the benefits of this community sports system.

His father, a passionate footballer himself, founded the DM Rao football club in Sekmai, Imphal, when Renedy was a kid.

The club, which still plays in the Manipur state league, was a way for him and his friends to stay engaged with sports after their professional dreams faded away.

The idea of a sports club is so deeply ingrained in the state's ethos that when Janajit Thangjam, an engineer and D license football coach, shifted to Bengaluru for work, he founded a club, North East Youth FC (NEYFC), of his own.

"Not because I want to become an ISL (Indian Super League) club or anything," Thangjam says, "It's to provide kids a place where they can learn and most importantly, love football. The larger idea, of course, is that for sports to grow; the grassroots need to be strong and clubs like this are necessary for that."

While football clubs dominate the state's sporting landscape, other sports flourish, too.

Since the Mary Kom revelation, boxing has boomed, and Anita Chanu thinks the latest silver will see a rise in weightlifting.

"The chief minister called and asked me to draw up a budget. The government wants to invest in more facilities, better equipment and infrastructure," she says.

"We are in lockdown right now (Manipur has seen a steep rise in COVID-19 cases over the past month) but my phone has been constantly ringing with parents asking how they can get kids enrolled."

Renedy tempers expectations by pointing out that all of this has happened before; this attention ebbs and flows. Whether it translates into more investment is the question.

"One of our big problems is getting corporate investment in sports here," Renedy says.

"Most investors are based in Mumbai and Delhi and whatnot, and they prefer to invest in places they are familiar with. No one wants to invest in an academy in Imphal. It's tragic but it's the truth."

What this means is that most talented sports persons quickly outgrow the resources within the state and hunt for greener pastures westward.

Mirabai Chanu's return to Imphal has been gloriously captured across social media as the return of the prodigal daughter, but it is telling that this return has been a long time coming.

She shifted out of Imphal in 2015, and has only ever gone back to visit her family intermittently. And while this is today's tale, Renedy's is no different.

Having outgrown D M Rao, he was selected into the Tata Football Academy (TFA) in the early 1990s.

While the benefits of that system were many, Renedy questions why they couldn't have been closer home.

"Manipur contributes so many footballers to so many clubs across India," he says. "But somehow at home our clubs are struggling to put together resources to train players. To date, we don't have the kind of infrastructure, a place like TFA had."

This problem extends to other sports in different ways.

"Many many years back I remember talking to someone in the state sports association and he informed me that Manipur had finished second in the National Games," Roy says.

"I was thrilled. It was a great thing right? Such a small state finishing so high. I asked him who finished first and he said it was the army. Then he paused for dramatic effect. 'But sir, most of the athletes in their team were from Manipur,' he laughed."

Manipuri athletes quickly realise opportunities are limited at home and move to get government jobs or in the Services as soon as they are able.

"Brother, you can idealise it and say everyone plays for the love of the sport," Renedy grimly says. "But the truth is everyone wants the money, too."

This extends all the way in the system. Silver medallists aren't immune to the charms of financial security.

Aside from the Rs 1 crore (Rs 10 million) cash award, one of the first announcements Chief Minister N Biren Singh made to recognise Mirabai Chanu's achievement was to guarantee her a job as an additional superintendent of police.

A Railways employee for many years, Anita Chanu says her ward had been seeking a promotion for a while now.

"I told her to focus on her performance and better things would follow," Anita Chanu beams. "And look! I was right, no?"

And despite it all, the financial hardships, the meagre infrastructure and the lack of mainland attention, the Manipur factory line churns on, producing athletes at a pace matched by few states in the country.

Renedy says the youth know that sport is perhaps their best chance to escape and with so many role models around it's really tough to aspire to much else.

Roy, for his part, thinks the reasons for sporting desire is influenced by other spheres of culture, too.

Manipuri performance arts, he says, lay the foundation for its culture of sport.

"It is no accident that one of the four foundational sources of what we know as Manipuri dance, the classical form, is a martial art called Thang Ta. Our society is deeply affected by physicality in performance. Tabalchis, for instance, sit down and play. Pung Cholom drummers spin in the air when playing."

"I always joke that one of the reasons we don't have an art tradition in Manipur is because art requires you to sit down and paint," Roy laughs.

"Jackson Pollock may have been very popular in Manipur actually."

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com