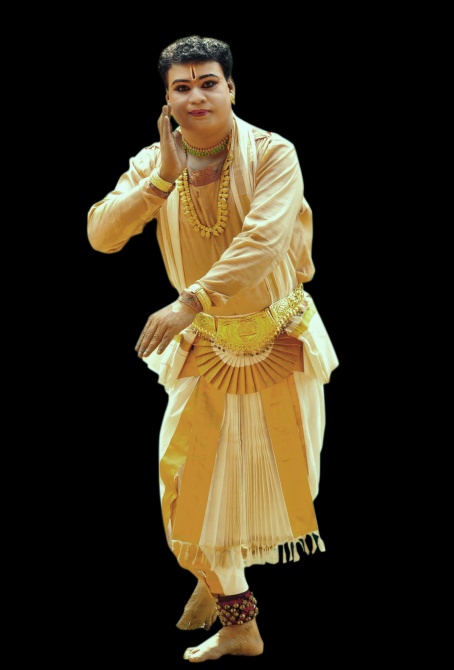

There is nothing unusual about a Muslim man taking a PhD in a dance form. But the feat becomes interesting when the dance happens to be Mohiniyattam, a Hindu temple art form, says Shobha Warrier/Rediff.com.

K M Abu, 47, is wondering why everybody is giving so much importance to his religious beliefs.

Upon closer inspection, it turns out that his achievement is amazing, all right, but not for the reasons most people think it is -- it is laudatory because of the odds he had to face and the hurdles he had overcome to chase his childhood passion -- odds and hurdles arising not out of his religious identity, but the poverty he grew up in.

It was not easy growing up in a rented house in Wayanad, Kerala, as one among the five children of Mohammed and Ummukulsu.

“Life was tough with my father working as a farmer; somehow we made it through each day,” he says.

Abu’s interest in dance was kindled when two girls in a nearby rich household showed him the dance steps they had learnt from their teacher.

“I didn’t know whether it was Bharatanatyam or Mohiniyattam, but I loved imitating what they did. Those who saw me dancing said, ‘this boy does quite well’, which in a way encouraged me to copy whatever they did. I started learning all that the girls learnt from their teacher. Nobody ever ridiculed me because I was a boy. In the school, too, I began to dance, choreographing my own steps, in order to entertain my teachers and schoolmates. This made me a kind of a hero in class!” he says.

Looking back, Abu says it was choreography that attracted him more than dancing. He began to choreograph dance moves for other students going to school youth festivals from a very young age.

It was at that time that Omana Vijayakumar, a classical dance teacher trained at the world-famous Kalamandalam (a major centre for learning Indian performing arts, in Thrissur district, Kerala), came to stay in Wayanad. She was the most acclaimed classical dance teacher to have come to the region at that time.

Once she began running classes, Abu could not resist the desire to learn dancing from her. So he went to her with a small dakshina, touched her feet and requested her to make him her shishya, while at the same time confessing to her that he had no money to give as fees.

Impressed by his passion, she made him her assistant.

“I travelled with her whenever she went to perform at faraway places. I was the boy who helped carry her bags! After some time, instead of me paying her fees, she began to give me some money for helping her, as she knew the background I came from,” Abu says.

That was how Abu’s was initiated into the world of classical dancing. It continued until he was in class XII.

“It was expensive to perform as a classical dancer and I had no means of doing it. So I used to participate in and win dance competitions at the district and state level in folk dance. At that time, I only wanted to learn classical dance for the pure love of it. I was not even thinking of performing on stage. It was unimaginable for a poor boy like me then,” says Abu.

When his teacher got a job in Ooty and left Wayanad, it was a big blow for him. But then, local temples started calling on him to perform and many families wanted him to teach their children.

The next turning point in his life was when a dance teacher from the Tripunithura RLV Government College of Music and Fine Arts (a college that boasts among its alumni, Carnatic musician and film playback singer Yesudas) happened to see one of his performances at a temple and suggested to him to take dance up as a serious pursuit.

At that time, Kalamandalam did not admit boys to learn classical dance forms that weren’t Kathakali (a classical dance drama form). Fortunately, though, the RLV college had no such gender restrictions.

It was so tempting for Abu that he immediately made a trip to Tripunithura to make enquiries.

“I took the advice of my teacher and joined the college in 1986 to learn Bharatanatyam. The biggest attraction was that I didn’t have to pay any fee, as it was completely subsidised by the government. But I had no idea how I was going to stay and feed myself,” he says.

He devised a plan to sustain himself: studying at Tripunithura during the week and rushing to Wayanad in the weekend and teach students what he had learnt. He found 30 students at Wayanad. In addition, he tutored students at a local school in Wayanad folk dance.

“Altogether, I made around Rs 1,000 a month. This was enough to feed myself and get a roof over my head, but it was extremely physically strenuous! After my classes ended on Friday, I caught a night bus to Wayanad. After teaching dance for two days, I took the night bus to Tripunithura to rush to classes on Monday,” he says.

Abu confesses that there were times when fear and disillusionment gripped his mind and he considered abandoning his studies altogether. It was only his passion and positive attitude that helped him tide over those difficult days.

By the time Abu reached the third year of his studies, he started running evening classes in nearby Ernakulam on weekdays.

“There was more money and life was not as difficult as it was from a financial perspective. But life got even more stressful and exhausting. But I had to do it in order to keep my stomach full,” he muses.

By the time he had graduated with a first class in a 4-year-diploma course and a subsequent 2-year-post-diploma in Bharatanatyam, he had become quite well-known in his hometown in Wayanad, as his students had begun to win dance competitions.

“I was the only Muslim dancer in the area but that was not a big thing there as they had seen me dancing since the time I was a child. My family was so poor that they never spoke out against what I did. As long as I didn’t ask for money, they had no issues. They didn’t even know what I was studying in Tripunithura,” he chuckles.

He also got a lot of programmes to perform in all the temples during festivals.

“I chose those temples with stages outside, as I didn’t want to create any issues. But I feel the late '80s and the '90s were a different time. Nobody looked at me as a Muslim dancer; I was just a talented dancer. In fact, in my town, our temple festival started with my dance performance on the first day for six-seven years continuously. It was an unwritten rule that all the temple festivals in our place would have my performance on the first day,” he says.

“People were quite liberal those days. But sadly today, religion has taken a front seat. Back then, every single person in the village was expected to participate in the temple festival; it didn’t matter if they were Hindu or Muslim. My mother used to unfailingly come and watch me perform at the temples, every year. I was invited to dance at temples in the neighbouring villages too,” he says.

“But in the early '90s, there were occasions when people asked whether they could write a Hindu name (for me) in the publicity material! But I was never interested in changing my identity just to dance,” he says.

Though he had studied Bharatanatyam, it was Mohiniyattam that interested him the most. But the RLV college offered no courses in Mohiniyattam at the time.

“I don’t know what attracted me. It may have been the expressions, the slow music, the unusual steps, or the striking costumes. My desire was not to dance; but to learn, teach and choreograph,” says Abu.

Abu was so fascinated by Mohiniyattam that when the RLV started running a course on it, he enrolled himself as student again for the four-year diploma course.

By this time, he was 24 and already married. “Shyla, my wife, is also from a poor background. Perhaps that was why they were not bothered about me being a dancer. Though she doesn’t dance and doesn’t know much about it, she helps and supports me a lot. To this day, she encourages me wholeheartedly. But it’s not just her; my extended family -- uncles, cousins and so on -- are also proud of my achievements. I am happy that they talk about me with so much pride,” Abu says.

He was a student again, but he kept his family going from his income as a dance teacher.

“Dance is my passion, but it’s also my daily bread and butter,” Abu says with quiet pride.

In 1996, Abu graduated with a first-class diploma in Mohiniyattam. And then, in 1997, when the Sanskrit University in Kaladi advertised vacancies for tutors in Bharatnatyam and Mohiniyattam, Abu applied.

“The interview board was pleasantly surprised to meet a Muslim man who was as qualified in both disciplines as I was,” Abu says.

Not surprisingly, Abu was selected to be a tutor in Mohiniyattam at the university.

In 1999, for the first time, the university started degree courses in dance and music and RLV soon followed suit. But since that put alumni with just diplomas at a disadvantage, the college agreed to admit the old diploma students for a two-year post-graduate degree course.

Abu took unpaid leave from the university and joined the college to take a post-graduate degree in Mohiniyattam as his ultimate ambition was to get a doctorate in the form.

And after finishing his degree at the RLV, he went back to his old job at the university.

Then, in 2007, when Kalamandalam became a deemed university, he joined their PhD course. His research was on the work of Kalamanadalam Kalyanikutty Amma, a legend in the field of Mohiniyattam.

Thus it came to be that Abu was awarded a PhD by Kerala Kalamandalam in January 2015, becoming the first Muslim to ever have received the honour in a dance form.

“My ambition is not to dance but mould today’s students by imparting good knowledge. I want to work hard for my students, and my happiness and satisfaction lie in the success of my students,” he says.

Though Abu’s daughter has decided to be an engineer, his niece has joined Kalamandalam to learn dance, following in her uncle’s footsteps.

Abu was a little pained by the changes that have taken place in society, the division between people of different faiths, but he says his life was never affected negatively.

“In fact, I have received only respect and appreciation from people all around me. Nobody has criticised me or ridiculed me for being a dancer of a temple art form. All the people I know including my colleagues are happy with my success. Personally, I have never felt discriminated against in the field of dance or academics, from the time I started dancing till today," says Abu.

After pondering for a while, he came up with an explanation for the kind of acceptance and respect he gets.

“I have come from a very deprived background. Now I am a professor in some college, which gives me a certain social status. I have found that when a person achieves social and economic status in society, he is accorded respect irrespective of his religion. If I am respected in society today, it is all because of my art. My request to the narrow-minded people is, not to mix religion with art. There is no religion in art. At the same time, I see lots of students from other religions also coming forward to learn the beautiful art forms, which is so heartening for an artist like me,” he says.

One thing is for certain, though; all Keralites are proud of Abu’s success and ability!