As India turns 70, a 70 year old -- one of India's finest poets -- decodes his relationship with her.

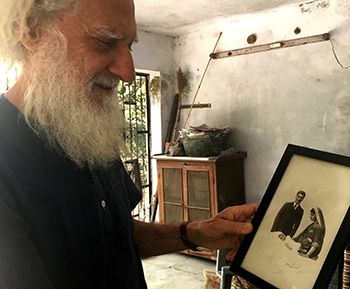

As young as India itself, poet and retired university professor Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, was born in Lahore four months before India became a free nation.

Sitting in his family home in Dehradun, where he had arrived as an infant at Partition with his mother, he periodically gets up to speak to his mother, who is now 92 and in fragile health.

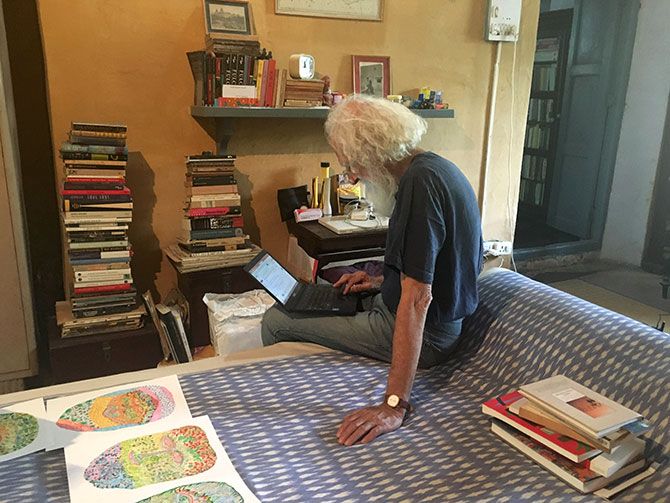

In conversation with Rediff.com's Archana Masih, the author of five volumes of poetry, two translations and editor of acclaimed anthologies on Indian literature examines these 70 years alongside India.

I grew up in the 1960s when there was plenty of nation building activity. My father was employed in Bhilai where the steel plant was being built.

People from all parts of India came to work there. You could see the blast furnaces come up and the Russians on the streets (who helped build it).

I went to the Bhilai Steel Plant School and am public school sector educated. I have worked as a teacher all my life.

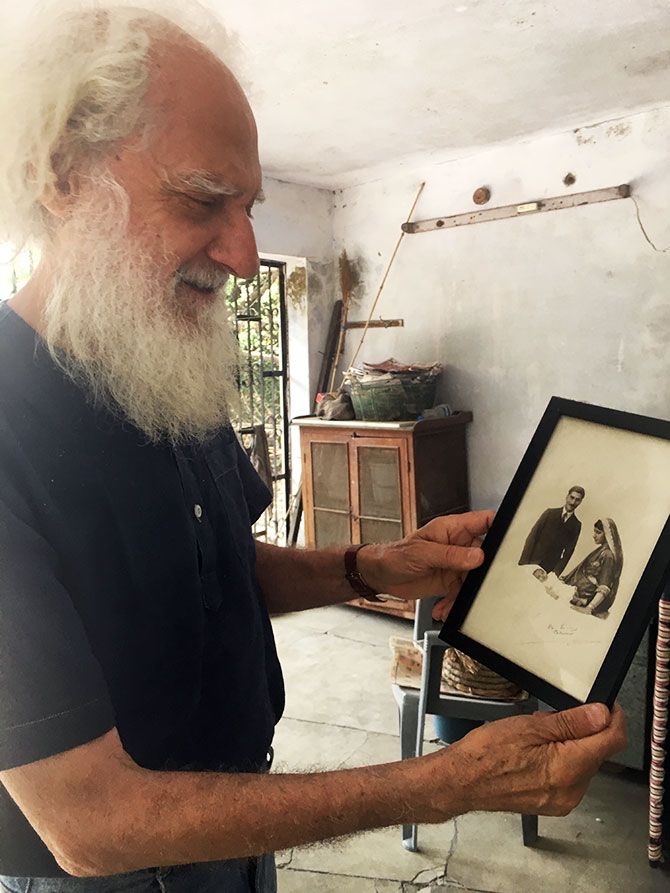

My family left Lahore with nothing much.

I discovered a wooden Kashmiri box with my mother's things -- letters and postcards from her school in Lahore -- but white ants got to them.

Her father worked in public health. They moved to Simla after Partition. She never talked about it much, but her brother, Ved Mehta, has written about those days. I never asked her for her memories.

'In America, I would forever be from somewhere else'

I don't think in terms of countries. I am almost indifferent to it.

I don't understand country just like I don't understand religion.

There was no concept of a nation till about 150 years ago. There were empires. The Ottoman empire and the Austro Hungarian empire.

Nation States is such a recent phenomena, but we pretend as if they had always existed.

Home for me is my home in Allahabad or Dehradun.

I was in America for two years when I was 23, 24, but I couldn't have lived abroad.

In America, I would forever be from somewhere else.

I realised I couldn't write about America. The landscape didn't affect me, I didn't understand the society.

'The English speaking elite doesn't know an Indian language'

I don't think we have a national language; we may have an official language.

Nehru was very clear that English was going to remain and all Indian languages were equal.

Why should anyone learn Hindi apart from the Hindi speakers?

I am a Hindi speaker, I have translated from Hindi, but my great regret is that I am not fluent in Hindi as many of my friends are.

Why is it that we do we not like to read it?

It is because the text books prescribed in our syllabus emphasised on the classics, not contemporary Hindi poetry. It sounded artificial and removed from daily life that one stopped reading it.

We skip that language because of poor schooling.

It is a peculiar Indian situation when you start hating your own tongue.

No other society does that. The English speaking elite doesn't know an Indian language.

Language also keeps changing.

Mixing Indian language with English is alright. That's the way we speak.

Language is not a pure element, basically it is meant for communication.

'Dissent is written into our tradition'

Indian culture and tradition is very diverse.

Every state, each tribe is very distinct from the other.

India is not a single text society. It never was. Dissent is written into that tradition.

The Bhakti movement was a movement of very strong dissent. The 2,000-year-old Prakrit poems have been quoted ad nauseum in Sanskrit text. The poems show that it was a very open society.

If the kind of people that exist now had been around 2,500 years ago, we couldn't have got so far.

No idea can be anti-national. Ideas are open to questioning.

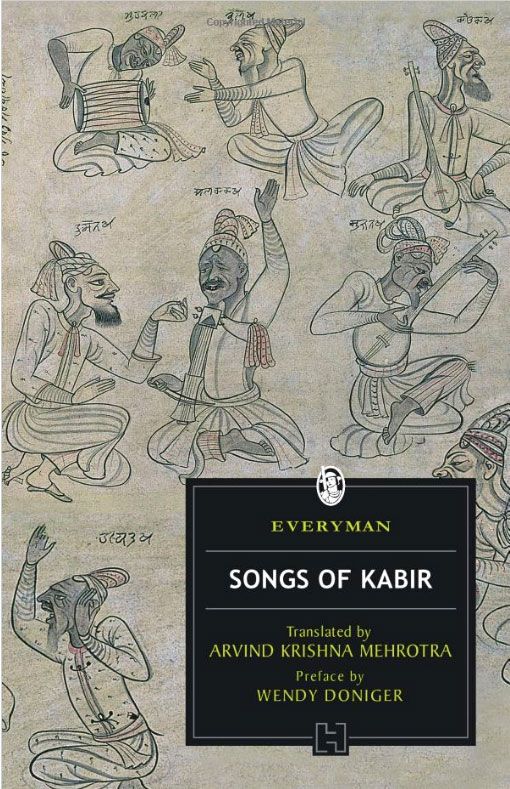

In today's time, Kabir would not have been allowed to open his mouth, the poet feels.

'Thought is dangerous. It is like fire'

Kabir was staunchly anti caste and expressed his views strongly. He also faced opposition.

One of the great Kabir stories, apocryphal of course, is that he was bound in chains, thrown into the Ganges and he miraculously survived.

Tukaram's manuscript was burnt, but it floated up to surface and was dry.

What it shows is that there was an attempt to suppress thought, but thought somehow still managed to free itself.

Thought is dangerous. It is like fire.

The emphasis on tradition is basically focused on shackling the woman.

Women have a hard time in this country. How often have they been told these clothes are against Indian culture, that you invite trouble when you wear that, that you can't marry out of your faith?

How much worse can it get?

Now you can't even eat the food you want!

'The Indian mind loves strictures'

In the '60s, there were no brakes on expression.

No one thought twice about expressing himself. People have now been killed for lesser reasons.

When the mind is squeezed and you scare free voices, it is dangerous.

It is also a very diabolical situation because it's a democracy, a free country with no censorship.

I don't think much will change. What happens in society is that once things come into effect, especially bans, it's very difficult to lift strictures. Like prohibition.

This country hasn't ever unbanned anything.

Like this beef ban, do you think it will ever get lifted? It won't. Certain changes are permanent.

Human beings have eaten animals to survive. Hunting and food gathering was a stage of human civilisation.

Bhang cultivation was banned under Rajiv Gandhi. Earlier, there were shops that sold bhang and it was a practice for thousands of years.

The Indian mind loves strictures. It loves being squeezed.

It doesn't like to change.

Economic growth doesn't mean very much unless you can think freely.

This closing of the mind has been happening for the last 100, 150 years.

The entire emphasis has been on clamping down.

We are enamoured of this whole idea of being unfree.

Accepting, not questioning anything.

The Indian is very easily browbeaten.

I am generally hopeful about the human race.

One is hopeful, but I don't know what I am hopeful about and where that hope is coming from.

INDIA 70 SPECIALS

- India, from the eyes of one who saw her birth

- 'The Ashokan Edicts are a marvel of history'

- A morning with the first Indian in space

- When India's President served a meal

- 'The Kailasha temple in Ellora is India's greatest treasure'

- The American who fought for India's freedom

- The Aussie who took on the British for Rani Laxmibai

- The Englishman who was more Indian than the Indians