'The quality of justice is directly linked to the quality of judges -- if that suffers, justice delivery suffers.'

In the leafy lanes of Golf Links, one of New Delhi's most coveted addresses, the calm is almost disarming.

Just a short stroll from Khan Market -- often ranked Asia's most expensive retail destination -- lies the home of senior advocate Dushyant Dave, whom we are meeting for lunch.

There is a reason we're here rather than at a restaurant: Dave prefers to eat at home, a habit he has largely maintained through a long and successful legal career.

All the more surprising, then, when last month he sent a short WhatsApp message to Bar and Bench and Live Law announcing that he was quitting the profession -- with immediate effect.

Was it a spur-of-the-moment decision, we wonder as we follow a cobbled pathway flanked by trees and shrubs into a courtyard with rich, dark wooden panels and dense foliage.

On one side of it is a sculpture that recalls Rodin's The Thinker. But unlike the famed figure lost in introspection, this one gazes outward, contemplative, yet watchful.

Much like Dave himself, it balances thought and leisure. In one corner of the courtyard is his office, barely 3 kilometres from the Supreme Court, where he practised for decades.

Across it is his home.

Inside, a tastefully done up waiting area that leads into the living room reflects the man -- cerebral and grounded.

A tall bookshelf dominates one wall, stacked with legal tomes and literary works.

Among them: A precarious Jenga tower, a copy of William Dalrymple's The Golden Road, and a child's bold, brushy artwork, possibly by one of Dave's four grandchildren, whose framed faces beam from a side table in the living room.

Everywhere one looks, there are artworks, both by modern masters like S H Raza and contemporary artists such as Paresh Maity, anchoring the space in colour and memory.

We are soon greeted by Waffles, a white and grey Shih Tzu, who sprints toward us with the enthusiasm of a rookie lawyer on the first day.

He leads us into the living room where Dave's wife Ami, clad in a blush pink cotton salwar-kameez, welcomes us warmly.

As we settle onto the deep red sofas, Waffles, having exhausted himself in a flurry of joyful leaps, curls up on his rug beneath a tapestry and promptly drops off to sleep.

We ask Ami Dave about her husband's recent retirement. Stepping away after 48 years, right at the peak, is uncommon for someone of Dave's stature.

It was during a family trip to South Africa for Dave's 70th birthday that he discussed quitting, she says.

"Everyone said he should wait until he'd completed 50 years in law. But one day, after we got back, he came home from golf and said he was going to do it there and then."

The couple are childhood sweethearts from Ahmedabad. "I was a swimmer, and Dushyant would wait until my practice," she laughs.

"When we married -- he was 25, I was 23 -- he didn't even own a bicycle."

Looking around their art-filled home, it's clear the intervening decades have been kind.

Just then, Dave walks in from his study, apologises for the brief delay, and jumps right in.

"I had a great run as a lawyer, but I have been frustrated for a while with the state of the judiciary and the country," he says.

The former president of the Supreme Court Bar Association lists his concerns: India's extremely low per capita ratio of judges, poor infrastructure, especially in the lower courts, and weak assistance to judges from lawyers.

"The promotion system is opaque. Many deserving candidates don't make it," he says. "Some great judges do rise to the high courts and Supreme Court, but they are the exception. The quality of justice is directly linked to the quality of judges -- if that suffers, justice delivery suffers."

He then talks of corruption, which, he says, is part of a wider societal rot.

"Judges come from this society; they don't descend from Mars or the Moon. We, as a society, cut corners on GST, on cinema tickets -- it seeps into everything."

Lunch is served, and we head to the dining table. It's a traditional Gujarati thali that looks almost too pretty to disturb -- khichu, kadhi, assorted dhoklas, chana, pickle, chutney, puri, papad, roti, and more.

"Bon appetit", he says, and we dig in. The kadhi is the standout, though khichu -- glutinous and savoury -- also demands attention.

"I'm a capitalist at heart and a socialist in action," he says with a smile.

"I love money, but my actions have always been socialist. Every penny I took from my clients was accounted for."

He says if his son asked him today whether to join the legal profession, he'd say no.

"The system rewards compromise. Yes, some succeed with integrity, but they are exceptions," he says.

"In law, 80 per cent of the work is cornered by 20 per cent of the lawyers. Judges' or lawyers' children often have a head start. First-generation lawyers are left to scramble -- unless they move to the corporate side."

Dave's own father was a judge. "But he wanted me to join the civil services," he says.

"He told me, 'I can't even fund you for a year, let alone the 10 years it usually takes to establish yourself.'"

The turning point, he says, came when Justice P D Desai, a family friend, told his father: 'Maybe your practice didn't take off in 10 years, but your son's will in one.'

During the course of his career, Dave was with the National Legal Services Authority (Nalsa) for five years.

What he saw in those years, he says, left him deeply disappointed with the legal aid system.

"The best lawyers aren't engaged. Judges don't take legal aid lawyers seriously."

He also says he discovered Nalsa hadn't audited its accounts in two decades, and his attempts to raise the issue were brushed aside until Justice Ruma Pal ordered a CAG (Comptroller and Auditor General) audit.

He is equally critical of the body's spending priorities.

"Too much is wasted on ads and events. Are we selling detergent? Ask 100 people at India Gate what Nalsa is -- they won't know."

Dave is unequivocal on the need for diversity in the judiciary. "It's not just gender, it's about empathy," he says.

"Without Dalits, minorities, women in the judiciary, we lack perspective."

The numbers, he points out, are bleak.

"Just one woman judge in the Supreme Court -- Justice (B V) Nagarathna. One Muslim judge, when Muslims are some 16 per cent of the population. And near-zero Dalit and Adivasi representation."

Another round of small, fluffy puris arrives, but there is already too much on the platter. Dave waves it off, telling the house staff in Gujarati that nothing more is needed.

We move to broader concerns, and his voice takes on a note of urgency. He believes India must return to the wisdom and spirit of its founding leaders.

"We need to revisit the Constituent Assembly debates," he says.

"What we see today in Parliament and state assemblies is a sharp decline -- not only in the quality of arguments but also in the dignity with which they are made."

He contrasts the present with the early decades after Independence.

"If you open an All India Reporter from the 1950s to the 1970s, you'll find extensive, outstanding debates on every section of every Bill. Every provision was deliberated upon -- and it was all on record."

Today, he laments, the party whip dictates everything. "A Bill is introduced, everyone says 'yes', and it is passed. No one questions."

He recalls leaders such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who, he says, brought eloquence and conviction to the floor.

"Where is that kind of parliamentarian today? What we have now are angry exchanges and personal attacks. Each side tries to vilify the other. Parliament has ceased to function as an institution of the people -- it's now an instrument for political power."

And this, he stresses, is not just the ruling party's fault. "It's across the board. All parties have fallen prey to this. Standards have fallen because leadership has fallen."

Asked to name a favourite among India's prime ministers, he doesn't hesitate.

"Vajpayee. Though I didn't agree with his ideology -- I'm not right-wing -- I respected him greatly. He was a statesman. He believed in taking everyone along, including minorities. He was soft-spoken, cultured, never aggressive."

Indira Gandhi, he says, had moments of brilliance -- the Green Revolution, the 1971 War -- but also set troubling precedents.

"She began the decline in governance. Corruption set in, institutions weakened. The long-term consequences were damaging."

"We are not seeing any reversal in the decline of governance standards, the erosion of the rule of law, or the spread of corruption," he says.

What were the high points of a nearly five-decade-long legal career?

"Many, but a few stand out," Dave says. He remembers one of his earliest victories -- the Arya Kanya Mahavidyalaya case in Vadodara under the Town Planning Act.

"I was very young, and it was a complex matter involving a school's property rights," he says.

He argued before Justice Desai, a judge he reveres.

"He was like a god to me. I quoted a 200-year-old judgment -- Julius versus Bishop of Oxford -- from a book by (British barrister and judge) Lord Denning. It laid down a beautiful principle: That a decision must take into account all relevant factors and ignore all irrelevant ones. If not, the courts have a duty to intervene."

The judge, he recalls, was stunned -- not by the precedent, but by the fact that such a young lawyer had dug that deep. "I won the case. It's reported in the Gujarat Law Reporter."

Integrity, he says, mattered more than the win. "I would never accept a brief where a senior had already appeared and was dropped. That's just not ethical."

Now that he's stepped back from active legal practice, what lies ahead?

"We're planning to adopt a taluka in Gujarat, near Palanpur, and replicate a successful skill development model," he says.

His wife, who has been sitting with us, nods. He would also like to deliver lectures or be available as a speaker -- "all pro bono".

There are other ideas too, such as improving agriculture, launching social initiatives.

"We're speaking to experts, people who've worked with the UN, the Gates Foundation, industry veterans."

He is also of the view that the tenure of the Chief Justice of India should be longer.

"What's really hurting the Indian judiciary today is the rigid adherence to seniority. You can't reward seniority; you must reward excellence. When you promote judges solely on the basis of seniority, you dilute the quality of the justice delivery system," he says.

In the UK, he adds, the chief justice is appointed through a public process.

"There's an advertisement, the candidates submit essays, and they appear before an interview panel of three members. There's no question of seniority. None."

He has a strong opinion on judicial appointments, too.

The government, he says, sits on files it doesn't favour, despite the Second Judges case (1993), which established that if the Supreme Court Collegium reiterates a recommendation after the government has returned it for reconsideration, the government is bound to accept it.

"If it sits on a file, the court can issue a writ of mandamus compelling a decision," he says. "No power can be exercised indefinitely. That's unconstitutional."

Dessert arrives: Chocolate pastries and delicate paan leaves from Dave's backyard. The paan is soft, sweet, and glides down our throats smoothly.

As we savour the final bites, we ask one last question: Does he have any hope?

Dave doesn't flinch. "None," he says. Now this is tough to swallow, but he persists: "I'm a proud, permanent pessimist."

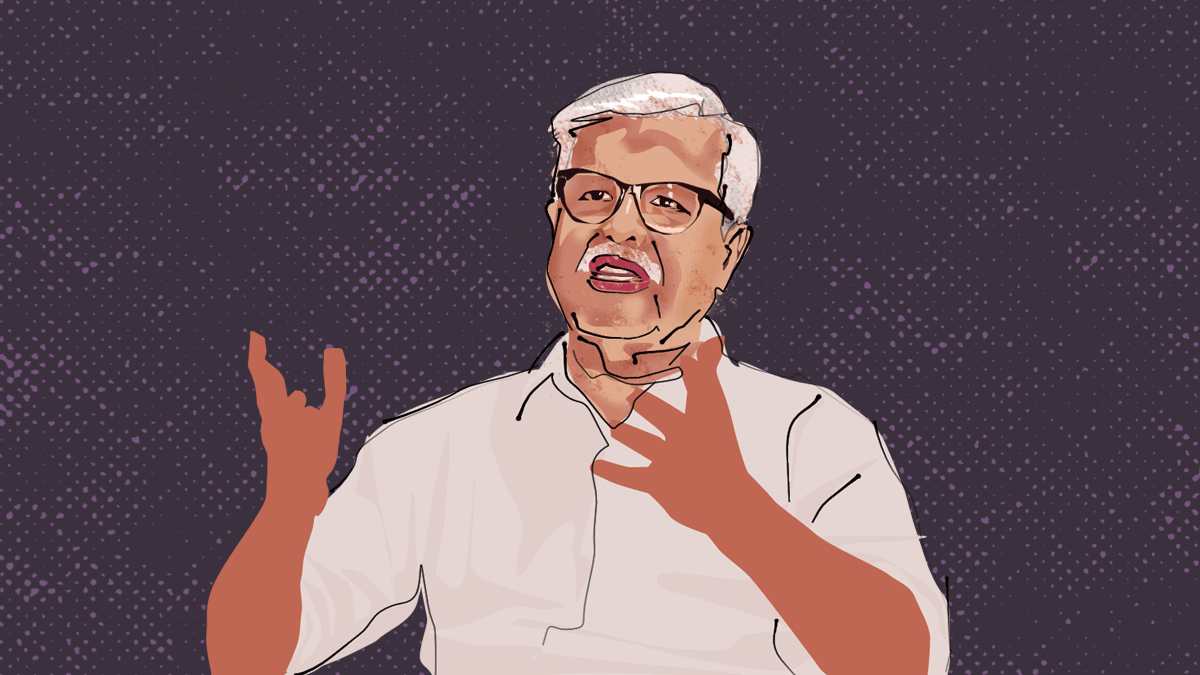

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff