'The unflappable temperament and nerves of steel under extreme pressure -- essential ingredients in space research -- were on full display in the rows occupied by the scientists still engrossed in their monitor screens,' says Minnie Vaid, author of Those Magnificent Women And Their Flying Machines, ISRO's Mission to Mars.

September 7, 1.10 am

It felt like my own exam result, those last 45 minutes before the much-anticipated and scheduled landing of the Chandrayaan 2 lander Vikram, on the south pole of the moon.

The tension, the wait, the knotted stomach -- and the unconscious appeal to a higher god for a successful outcome.

The rest of India and its citizens were doubtless united in the same prayer while space scientists worldwide also watched the landing unfold with interest and goodwill on their television screens and devices.

Half an hour later as the much-publicised 'Fifteen minutes of terror' (*ISRO Chairman K Sivan had termed the last 15 minutes of the lander's descent thus) began, all television channels switched to the live feed transmitted by Doordarshan.

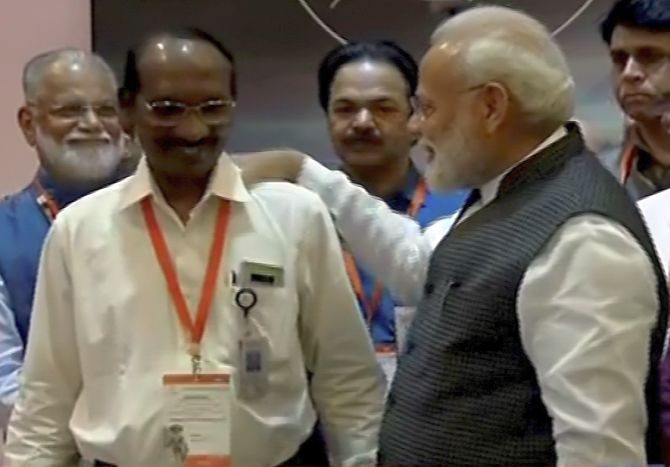

Prime Minister Narendra Modi joined former ISRO chairmen in the viewing gallery at the Mission Operations Complex or MOX at ISTRAC.

I began looking out for onscreen visuals of Chandrayaan 2's Mission Director Ritu Karidhal.

She was among the 21 ISRO women scientists I had interviewed extensively for my book.

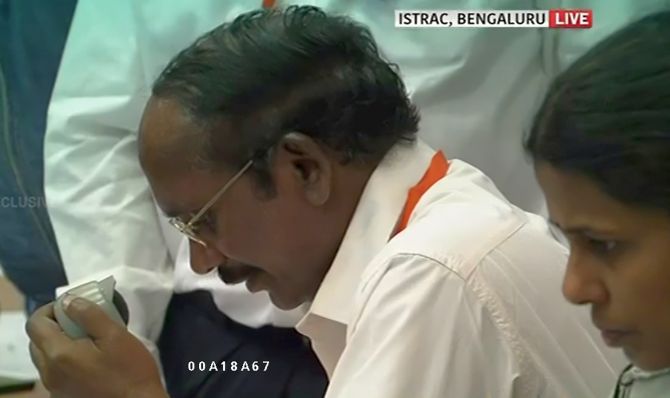

And soon enough I spotted her, dressed in a simple salwar-kameez and a jacket, seated among a row of men and women, all staring intently at the monitors in front of them.

She looked calm and composed, exchanging the occasional remark with her colleagues flanking her and giving what I presume were commands or directions from time to time, over the microphone she held in front of her.

As the descent crossed the rough breaking phase, applause and smiles swept across the room, allowing the rest of India a moment to breathe easy, fairly convinced now that success was just round the corner.

For the large majority who cannot decipher the trajectory of the lander that was shared in real time by ISRO, the claps were a promising sign.

Within minutes however -- at 1.49 am -- the mood changed drastically, silence giving way to disappointment and dismay all around, with the formal announcement by ISRO Chairman Sivan that communication with the lander had been broken in the final landing stage, just a few metres from touchdown.

A partial failure or a partial success of the mission, depending on your interpretation since the Orbiter continued in its lunar orbit transmitting data as programmed.

I looked for Ritu again and apart from a slight frown between her brows, the stoic expression hadn't changed much.

She continued to give the commands as needed, turning back in her chair to talk to senior ISRO scientists like S Arunan (her project director during the Mangalyaan mission) and former ISRO chairman Kiran Kumar.

The unflappable temperament and nerves of steel under extreme pressure -- essential ingredients in space research -- were on full display in the rows occupied by the scientists still engrossed in their monitor screens.

A short while later the prime minister left the premises, with the 400-strong media persons following suit a little later when it became clear no further information would be shared that night.

For the scientists however -- especially Mission Director Ritu Karidhal and her Project Director Vanitha M -- the night (and their work) was far from over.

Even as ISRO scientists and their Failure Analysis Committee or FAC would analyse data in the days and months to come, pinpointing where the lander's trajectory went off track, I couldn't help thinking of what the scenario would be like at Ritu's home that very morning.

Fatigue and disappointment would probably have to wait upon her domestic duties -- getting her two children off to school, supervising the rest of the day's schedule with household help, sharing notes with her engineer husband Avinash.

And then perhaps allowing herself a little time to collect her thoughts -- she had told me in her interview that 30 minutes of quiet contemplation gives her the energy needed for the day's work.

Three years ago when I met Ritu for the first time at the women empowerment seminar at the Indian Women's Network, CII, she impressed me enormously; as a slated speaker on her role in Mangalyaan she deftly drew a compelling picture of the intricacies of the mission, ending with a marvelous, matter of fact quote, 'We worked during the day and we worked during the night, somewhere in between we took care of our children/families and we also sent off a rocket towards Mars'.

It was this unpretentious, understated remark that sparked the idea of writing a book on the ISRO women scientists of the Mars mission.

A few months later at ISRO Bangalore, Ritu was as impressive in the detailed interview she granted me -- patiently explaining difficult scientific terms and processes.

When I met her at her residence a few months later, her professionalism and her warm hospitality struck me anew.

Sharing her relaxation tips (meditation and prayer) and unwinding with her children in her comfortable home, she acknowledged the dual role she plays on a daily basis, especially during mission times.

The fact that any mission always involves and emphasises team effort also means triumphs and setbacks are never considered the result of personal contributions, irrespective of gender.

ISRO has a strict mantra of rigorous reviews at each stage including time-bound performance reviews of satellites/missions, checking off different milestones at different times.

Anomalies such as the Chandrayaan 2 lander Vikram losing communication just before it was supposed to land on the moon, will mean immediate reviews, but these too will encompass (the role of) the entire Chandrayaan 2 team.

Today the path-breaking women-led mission to the moon has not culminated in the feeling of the goose-bumps Ritu Karidhal admits to each time she talks about Mangalyaan's triumphs five years ago.

But in the years to come, the women scientists of ISRO (along with their male colleagues) will leave their own footprints on not only the moon, but the entire universe.

'There's a story by Mitch Albom about the first wave of an ocean getting frightened of crashing against the shore and getting washed away. The second wave tells the first, "You are scared because you see yourself only as a wave. I am not scared because I see myself as a part of the ocean that cannot be erased." ISRO-ites are cohesive like the second wave, working together towards their goals.' Ritu Karidhal as quoted in the book Those Magnificent Women And Their Flying Machines, ISRO's Mission to Mars by Minnie Vaid.