Richard Zimler's novel, Guardian of the Dawn, documents the little-known Portuguese Inquisition in India, in 16th century Goa. He points out that, apart from their laws and religion, the Portuguese also imported and enforced their infamous methods of interrogation to subdue troublemakers.

Zimler has won numerous awards for his work, including a 1994 US National Endowment of the Arts Fellowship in Fiction and 1998 Herodotus Award for best historical novel. The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon was picked as 1998 Book of the Year by British critics, while Hunting Midnight has been nominated for the 2005 IMPAC Literary Award. Together with Guardian of the Dawn, these novels comprise the 'Sephardic Cycle' -- a group of interrelated but independent novels about different branches of a Portuguese Jewish family.

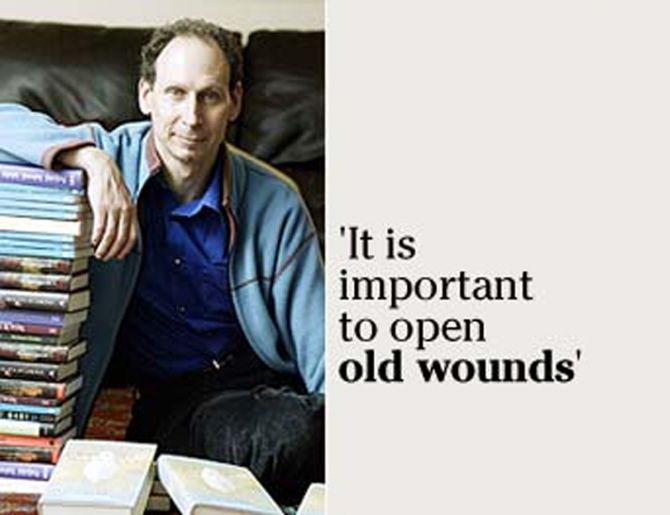

Intrigued by his novel, as well as his reasons for writing it, Lindsay Pereira decided to ask him a few questions.

You were born in New York and went on to study comparative religion. Why the decision to write about the Portuguese inquisition in Goa -- a whole other world?

About 15 years ago, while doing research for my first novel, The Last Kabbalist of Lisbon, I discovered that the Portuguese exported the Inquisition to Goa in the sixteenth century, and that many Indian Hindus were tortured and burnt at the stake for continuing to practice their religion. Muslim Indians were generally murdered right away or made to flee Goan territory.

I couldn't use that information for my novel but decided, a few years later, to do more research into that time of fundamentalist religious persecution. I discovered that historians consider the Goa Inquisition the most merciless and cruel ever developed. It was a machinery of death. A large number of Hindus were first converted and then persecuted from 1560 all the way to 1812!

Over that period of 252 years, any man, woman, or child living in Goa could be arrested and tortured for simply whispering a prayer or keeping a small idol at home. Many Hindus -- and some former Jews, as well -- languished in special Inquisitional prisons, some for four, five, or six years at a time.

I was horrified to learn about this, of course. And I was shocked that my friends in Portugal knew nothing about it. The Portuguese tend to think of Goa as the glorious capital of the spice trade, and they believe -- erroneously -- that people of different ethnic backgrounds lived there in tolerance and tranquillity. They know nothing about the terror that the Portuguese brought to India. They know nothing of how their fundamentalist religious leaders made so many suffer.

What were you trying to do with this cycle of novels? Did you set out, initially, to merely inform your audience about that period in history?

I always set out first to tell a good, captivating story. No reader is interested in a bland historical text. People want to enjoy a novel -- and find beauty, mystery, cruelty, love, tenderness and poetry inside it.

Within that story, I do try to recreate the world as it once was.

In the case of Guardian of the Dawn, I want readers to feel as if they are living in Goa at that time. I want them to see the cobblestone streets of the city and the masts of ships in the harbour, to smell the coconut oil and spices in the air, to hear calls of flower-sellers in the marketplace. I want them to feel the cold shadow of the Inquisitional palace falling over their lives.

In my cycle of novels, I have written about different branches and generations of the Zarco family, a single Portuguese-Jewish family. These novels are not sequels; they can be read in any order. But I've tried to create a parallel universe in which readers can find subtle connections between the different books and between the different generations.

To me, this is very realistic because we all know, for instance, that there are subtle connections between what our great-grandparents did and what we are doing.

The research involved in Guardian of the Dawn is obviously immense. Could you tell me a little about the kind of preparatory work you had to put in?

To write the book, I tried to read everything I could about daily life on the west coast of India -- more specifically, in and around Goa -- at the end of the sixteenth century. The Internet has made that sort of research much easier than it used to be, and I was able to order books about everything from traditional medical practices -- including recipes for specific ailments -- to animals and plants indigenous to that region.

When I write a novel, I want to get all the details right, so this is very important. Of course, it was also vital for me to know as much as I could about Hinduism and Catholicism. As you mentioned, I studied Comparative Religion at university, so this was pretty easy. One of the main characters in the novel is a Jain, which is a religion I have always been curious about, so I read three or four books about Jainism as well. It was wonderful to be able to learn a bit about Jain belief and practice. Writing is always a great opportunity for me to keep learning.

Tiago Zarco is a character you manage to strongly empathise with. Where did he come from? Was there factual data on someone he was actually based upon?

Yes, he's someone I really like -- and for whom I feel a strong empathy. He's a good man who is changed by his suffering and who decides to take revenge on the people who have hurt him and his family. But I did not base him on a real person. I think, in a way, he was born of my previous two novels, because I tried to make him someone who could fit into the Zarco family and yet be fully developed as an individual. With Tiago, I tried to ask the question -- how far can we bend our own moral code to fight evil?

In other words, can we use deception and even violence to try to destroy a cruel system of fundamentalist religious fervour like the Inquisition?

Re-examining the Inquisition seems apt, more so at a time like this when religious fanaticism is changing the world in ways unknown to us. What do you, as an author, believe we ought to take away from a study of it?

I couldn't agree with you more, and that is one of the reasons I wrote Guardian of the Dawn. Put simply, I think we all need to be alert to the intolerance in our societies and in ourselves. We ought to maintain government and religion completely separate -- such a separation is the only guarantee we have of freedom of expression. We ought to learn from the ancient Asian tradition, which is to respect the religious beliefs of others and not impose our own Gods on them.

Did you visit Goa at any point? If not, what did you base your descriptions of the state upon?

No, I decided not to go to Goa, because I didn't want any images from modern Goa to infiltrate into the novel. I didn't want to risk inadvertently putting something from today into it. So I based my descriptions on other areas of the world I've visited that have similar flora and fauna -- Thailand, for instance. Also, I read all I could about the city so that my descriptions of the buildings, for instance, would be accurate. I then used my imagination, which is the most important thing for a writer. I now have a landscape in my head that is Goa -- and the surrounding region -- in 1600. I don't know how it developed. It's almost magical.

Portugal, today, is still a country deeply steeped in a Catholic tradition. Do you think people are aware of the Inquisition and what it meant back then? Would they look at this as a re-opening of old wounds?

No, few people here know anything about the Inquisition. Many of them would rather not examine what their ancestors did, both in Portugal and its colonies. But others are very curious about what they didn't learn in school about their own history. Yes, in a sense I am opening old wounds. But I think it's important to do that. I think that we need to face the bad things we do -- both individually and as a society. In general, the Portuguese have been very receptive to my books.

Guardian of the Dawn has been a Number One bestseller here, for instance. A great many readers tell me I have opened a door to a part of their history they know nothing about. I'm proud of that. And I'm proud of having made it possible for Indians and Jews who were persecuted and imprisoned to 'speak' to modern readers through this novel. I think that's important because I don't want their suffering -- and their heroism -- to be forgotten.

As an author -- more specifically, an author devoted to history -- you have a unique perspective on the past. As a journalist, how important is examining the past to you?

As a journalist, it's important, because I think we can change the world by exposing past injustices. By writing about atrocities, we can change policy and avoid future wars. We can get war criminals punished. We can help people win fundamental human rights. Unfortunately, so much journalism is superficial and stupid that there is little room left for important articles.

Do you plan, in future, to base your work on other periods, or religious themes? Or do you plan to break away from the genre of historical fiction?

I have written a new novel that has just come out in England called The Search for Sana, which is about two women -- one Palestinian, one Israeli -- who grew up in Haifa together in the 1950s. It's about how their friendship is destroyed by political events that lead to tragedy for one of them. I am now working on a novel set in Berlin in the 1930s, in which one of the main characters will be a member of the Zarco family. So this will bring the cycle up to the 20th century. Where I will go from there is anyone's guess.

Read an exclusive extract from Richard Zimler's novel, Guardian of the Dawn!