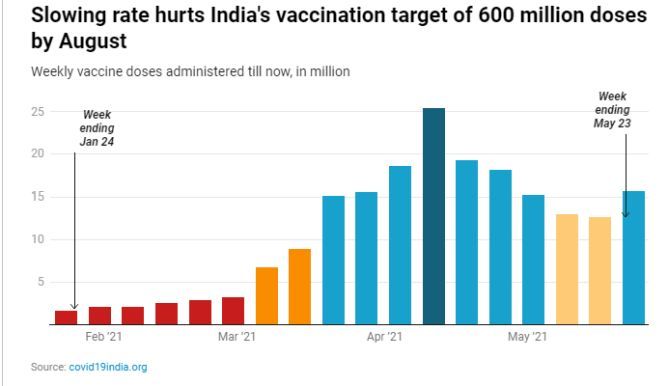

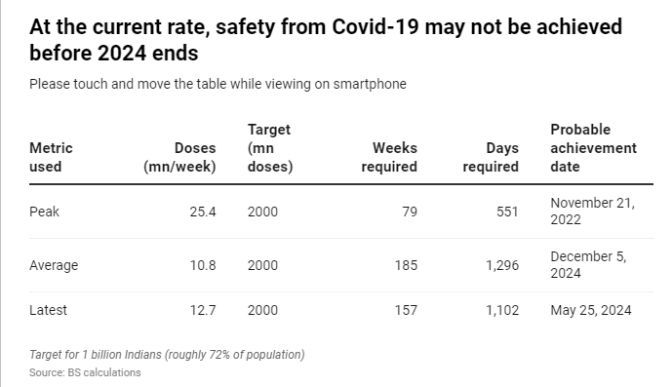

The average rate of COVID-19 vaccination in the country has been 10.8 million per week.

At that rate, it will take India till December 2024 to complete two billion doses, reports Abhishek Waghmare.

As vaccination crosses key milestones in many parts of the developed world, India is still struggling to get the basics right.

Unless the many brands of vaccines available in the market are procured in record quantities, the sluggish pace of inoculation in the country may last till the middle of 2024, even if it has to fully vaccinate one billion out of 1.36 billion Indians.

The average rate of COVID-19 vaccination in the country has been 10.8 million per week. At that rate, it will take the nation till December 2024 to complete two billion doses.

The rate for the week ending May 16 is 12.5 million doses per week. At this rate, two billion doses would be administered by May 2024.

India's best weekly achievement till now has been 25.4 million doses per week. Even this would stretch the programme till November 2022.

This will, to a great extent, prevent the economy coming back on track anytime soon.

What brought us to this position?

On January 16, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that India will vaccinate 30 crore (300 million) people in a 'few months'. The deadline was August 2021, for a task that would require 600 million doses. The math was simple: At 3 million doses per day on average, India would have achieved the target with ease.

The enormity of the ask

But the reality is different. Until May 18, India has fully vaccinated only 41 million people. In terms of the number of doses, 186 million have been administered till now, four months after beginning the vaccination programme.

It took India 122 days to administer 186 million doses, at an average rate of 1.52 million doses a day. In the 105 days to August 31, 2021, India will need to administer 414 million doses.

The asking rate for this, at 4.45 million doses per day, is thrice the current rate. This is the enormity of the situation.

Union Health Minister Harsh Vardhan told reporters recently that the government will be able to administer 516 million doses till the end of July, 14 per cent lower than the original target.

Even with this lowered target, 329 million doses need to be administered in 75 days, putting the required rate at four million doses a day, again nearly thrice as fast as the current speed.

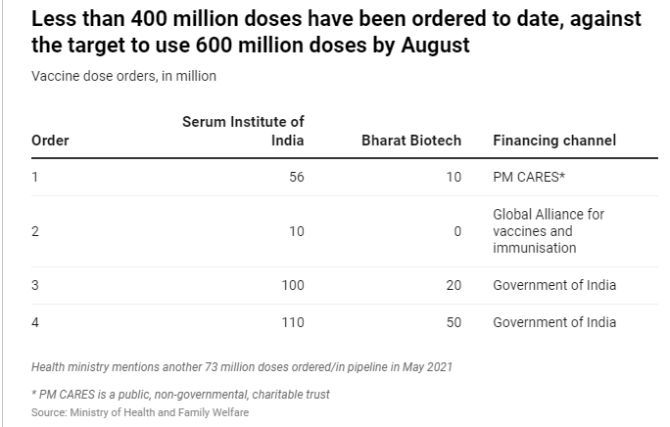

The primary reason for the slow pace and the failure to catch up is the snail pace of vaccine orders and procurement.

Patience in the time of urgency

According to the ministry of health and family welfare, orders for only 356 million doses have been put out to manufacturers, which include 276 million doses of Covishield, the Astrazeneca vaccine manufactured by Pune-based Serum Institute of India, and 80 million shots of Covaxin, the indigenous vaccine developed by Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech.

The ministry brief also mentions 73 million doses ordered/in pipeline in May 2021. The ministry has not made it clear whether they are in addition to existing orders or not. In fact, the government has not released data on vaccine orders in a transparent manner.

Against the requirement of 600 million doses till August 2021, some 430 million doses have been ordered at the most.

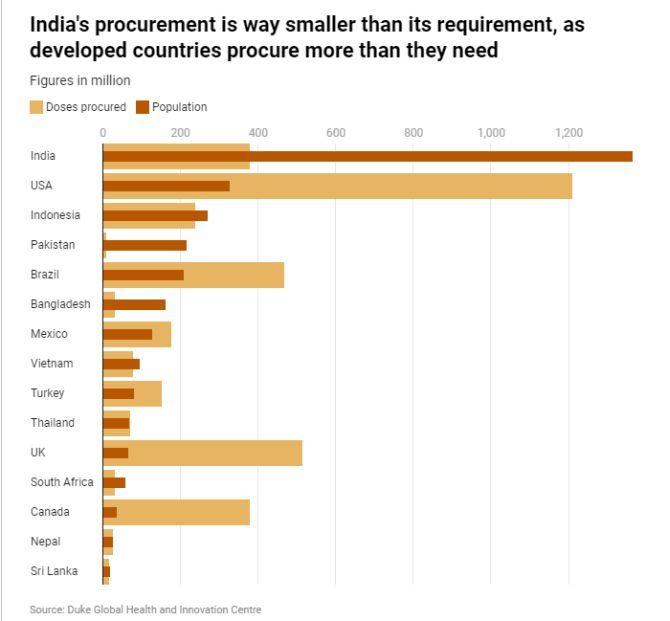

This is in stark contrast with how advanced countries and India's peers approached the top priority task.

Developed countries such the US, UK and Canada have ordered much more than they need. Emerging but relatively more developed peers like Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, and Turkey have ensured that orders till now make good for one dose for the population. Asian peers like Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka are in the same league.

Only neighbours Bangladesh and Pakistan are as behind as India is, in terms of orders placed already.

Cost of delay

Most agencies that track India's economy have reduced the forecast on real GDP growth by 1-2 percentage points. A single percentage point of India's real GDP is Rs 1.3 trillion, and that of India's nominal GDP, is Rs 1.95 trillion. It is likely that India has already lost Rs 2 trillion worth of value-adding economic activity in the current financial year.

This is what the economy loses.

Then there is a more indirect loss, that in government revenue. For an emerging economy like India growing at 7 per cent in real terms on average, the assumption of 10 per cent growth in tax revenue would be conservative. Applying this assumption, without COVID-19, India would have earned Rs 17.77 trillion in April-February 2020-21.

Instead, the actual earnings were Rs 16.66 trillion (gross tax revenue), a loss of more than Rs 1 trillion.

Why is this relevant here?

A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that fully vaccinating two billion Indians would require Rs 56,000 crore (Rs 560 billion) at the least, if the domestically developed vaccines had been procured early at Rs 300 per dose.

At the higher end, it could go to Rs 1.5 trillion, if half the vaccines administered are the costlier brands developed by Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna or Russia's Gamaleya Research Institute, assuming that their price tag is Rs 1,200 per dose.

Costs of vaccination are thus very much comparable to revenue losses the Indian government may incur in a situation of uncontrolled spread of the disease.

Till now, the Centre has spent less than Rs 8,000 crore (Rs 80 billion) on current orders, according to what can be deduced from available data. This is less than a fourth of the Rs 35,000 crore allocated in the annual Budget for the same purpose.

Not just costs, policy too matters

Most developed countries have kept vaccine procurement and supply centralised at the level of federal/central government. None of them have devolved this responsibility to sub-national governments.

Take the example of the United Kingdom.

'The vaccine task force moved quickly to sign deals to buy the most promising vaccines and the UK has so far secured access to 367 million doses from 7 vaccine developers with 4 different vaccine types. The UK was the first country in the world to buy the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, ordering 40 million doses -- enough for a third of the UK population,' the government of UK's health department says on its Web site.

Similar is the case with the United States.

'OWS is developing a cooperative plan for centralised distribution that will be executed in phases by the federal government, the 64 jurisdictions CDC works with (all 50 states, six localities, and territories and freely associated states), Tribes, industry partners, and other entities.

'Distribution has three key components: Partnerships with state, local and tribal health departments, territories, Tribes, and federal entities to allocate and distribute vaccines, augmented by direct distribution to commercial partners.

'A centralised distributor contract with potential for back-up distributors for additional storage and handling requirements. A flexible, scalable, secure web-based IT vaccine tracking system for ongoing vaccine allocation, ordering, uptake, and management,' the policy of the US says.

These countries are two of the most successful Covid-19 vaccinators to date.

Contrary to this, India has instituted a Liberalised Pricing and Accelerated National COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy, wherein state (subnational) governments and private hospitals have been told to procure 50 per cent of the vaccine requirement themselves.