'We are dealing with a size of the world that equaled England and France combined. We are talking about 250 years of history.'

Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700: Opulence and Fantasy -- a first of its kind exhibition anywhere in the world -- opened at the Met, April 20. Aseem Chhabra spoke to Navina Haykel, the curator of the show.

Navina Najat Haidar Haykel has been a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Islamic Art department for 15 years. She was instrumental in the establishment of the museum's permanent Islamic Art galleries.

Navina Najat Haidar Haykel has been a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Islamic Art department for 15 years. She was instrumental in the establishment of the museum's permanent Islamic Art galleries.

In 2011, Holland Cotter of The New York Times called the gallery 'as intelligent as it is visually resplendent,' adding, 'The art itself, some 1,200 works spanning more than 1,000 years, is beyond fabulous. An immense cultural vista -- necessary, liberating, intoxicatingly pleasurable -- has been restored to the city.'

Haykel and her colleagues are now presenting another piece of Islamic Art from India -- the grand new show Sultans of Deccan India, 1500-1700: Opulence and Fantasy runs from April 20 to June 26, 2015.

It is a first of its kind show anywhere in the world and a must see for lovers of arts from India. The show could be a life changing experience for those who know little about Indian history and that too from the Deccan.

Haykel spoke to Aseem Chhabra a couple of weeks before the opening of the show. She was busy finalising the exhibition catalogue and referred to images as she spoke about the challenges putting together a show of this magnitude.

Navina, I know you had been working on this exhibition for many years, but I am curious how this idea came about -- this specialised part of Islamic Art, set just in the Deccan region with all the layers of trade and different influences?

When I first joined the museum, the head of department was Dan Walker, who is a specialist on Mughal textiles and carpets. He did the famous show Flowers Underfoot: Indian Carpets of the Mughal Era. Dan was my first boss here and it was his dream to always do a Deccani exhibition.

It sounded fantastic. Then he left and moved on to other things and I inherited the project from him. It was not my concept and I am nervous about doing justice to someone else's dream. But he is very much a part of the symposium.

How long does a show like this take?

It takes a very long time. Art historians like us are trained to identify and develop true subjects. Some categories of art are already identified as great art like the Mughal paintings, usually arts connected with patronage of the rulers of a dynasty. That forms a cohesive whole. That very much applies to the arts of the Islamic world. This is a court-based patronage system.

The Deccan Sultans were great patrons of the arts. But the patronage of the Deccan courts had never been fully explored or even established. This is the first exhibition of the subject ever.

The real driving factor here is the extraordinary quality of work. It is on par with any great period of Indian or world art. But it was charting uncharted territory.

A lot of what we do is like detective work, because many of the pieces are split up. Look at this one (she points to the palanquin finials from the Golconda region) -- two are in our collection, two in private collections in New York and then there are three other parts in private collections. Just to put this work together we had to track each piece.

How do you keep track of all of this? Do you follow all the auction houses sales?

Yes. But the thing is to have strong friendships and partnerships. You have to think of objects, the way you think of people. Your life is defined by them. You notice who owns what, where they sell, how much are they going for? It becomes a part of your DNA.

We are just academics and keep a dispassionate view of the art. But there are collectors who are the most passionate people, tracking who owns what. One owner of the part of the palanquin knows where the other pieces are. One day he hopes to acquire the other pieces.

In this case, how did the collectors get the pieces?

There was a well-placed family in India who moved to the West and they brought parts of the palanquin with them. They worked through a dealer. They broke it up and sold it, not all at one time, which complicated the matter. Reconstructing it becomes a story by itself.

We have diamonds in the exhibition. Diamonds travel around the world. Before the discovery of diamonds in Brazil in the 18th century and Africa in the 19th century, all the world's diamonds came from the Golconda region. We have put together some major diamonds from the Golconda in this show.

We are trying to introduce diamonds not just as valuable gems, but the art and taste for, how they were carved and treated. There is the Indian taste -- an auspicious tabeez, an amulet, with no setting and cutting, with a simple string drilled through. When you get to the West the diamonds, there have a totally different aesthetic and shape as they are cut and have a glitter.

The British public was disappointed when they first saw the Kohinoor since it was not glittering. It had the luster that the Indian eye appreciated, but not the glitter.

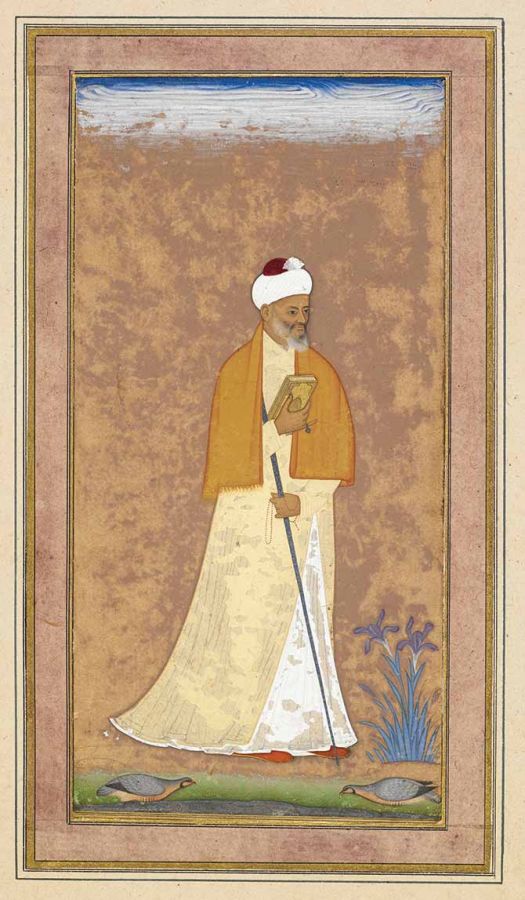

Among the great glories of the show are the Bijapur paintings. This is a portrait of a mullah, a religious authority who is holding a golden book and he is wearing the robes of a scholar. But it's the face that is so extraordinary. He is probably an Arab scholar. Look at the flesh hanging from the side of his nose, the shaded beard.

Among the great glories of the show are the Bijapur paintings. This is a portrait of a mullah, a religious authority who is holding a golden book and he is wearing the robes of a scholar. But it's the face that is so extraordinary. He is probably an Arab scholar. Look at the flesh hanging from the side of his nose, the shaded beard.

Where does this piece come from?

This piece is from the British Museum. We are showing three similar style paintings, another one from the British Museum and the third from the San Diego Museum of Art. The artist is known as the Bodleian painter because his masterpiece is in the Bodleian Library. Sometimes we know very little about the artists.

There is another remarkable painting that is supposed to represent a dream that Jahangir had. With Jahangir standing on top of a globe, on top of a cow, on top of a fish -- that's an Islamic idea of the structure of the universe. You have cherubs handing divine arrows and with a golden bow he shoots the head of Malik Amber. This is a part of the group of allegorical pictures made by Abul Hassan.

So again starting from the concept, to planning, the search goes out to find pieces.

How long does it take and how big is your department that worked on this project?

I have two partners -- Marika Sardar and Courtney Stewart. Marika has a PhD in Deccani architecture. And then we have specialised scholars who have written for the catalogue and other advisors.

Typically a big exhibition like this takes five years to plan. We spent much longer because I got busy with the permanent Islamic Art galleries in between, which opened three years ago.

During that period we were also slowly working on this show and we also organised a symposium on the subject since by then we had gathered so much stuff. So we captured some of the scholarship in the symposium.

And five years is not that long for a show of this size. We are dealing with a size of the world that equaled England and France combined. We are talking about 250 years of history.

Then there is a huge amount of unchartered architecture. There are forts and palaces in northern Deccan that are not under any protection and virgin territory for anyone to study.

When the Met decided to work on this show did all other museums around the world know about it? And no one else would plan it at the same time?

This is a very difficult exhibition to organise. You need very specialised scholarly skills. Plus you need the money to put it together. The pieces were scattered. The Deccan kingdoms were completely destroyed by the Mughals and then the arts spread all over the world for various reasons.

To get 150, 200 objects together in a room you have to borrow from 70, 80 people and institutions. We had to even think of borrowing from Madagascar, although in the end we couldn't because it was too expensive.

What were you looking for from Madagascar?

There was a box we were trying to reconstruct that had four sides and it was broken up. We tracked each side. The fourth side was in a small museum on an island off Madagascar.

It was a forbidding budget because of the plane and the insurance. At some point the budget realities began hitting us. So we only have one side of the box here.

This is again detective work?

Yes. India is full of mysteries. Things are not recorded well and people are secretive. Museums are not well catalogued. The Archeological Museum in Bijapur is now renovated, but for a while only we knew that there were two seven foot crocodile water spouts in the basement. It was a great find.

Where will the show be staged?

It is just off the Greek and Roman galleries. It is a mid-sized space. The scale of the object is small, so it is an intimate setting.

We are going to do a very exciting installation. We will really transport you to the Deccan by using these amazing photographs by Antonio Martinelli. It will be a special entry.

We want you to experience the art. We take our cue from the objects. What they feel we give it to them.

I read you did your DPhil from Oxford. What was your specialisation?

It was in Indian painting.

And where did you go after that? Was it directly to the Met?

The Met is the only job I have had. I did a little project at the Brooklyn Museum of Art when I first came to America. I was locked in a room and asked to catalogue about 400 objects. Most of them were little Hindu and Buddhist bronze sculptures from a private collection.

It was a great education. I had some vague idea about the time period, but I had to figure out a lot.

I wanted to talk about the fact that it is Islamic Art and the times and the city we live in.

I read there was once a controversy whether the entrance of the Islamic Art show should have a page from the Quran. How do you deal with the outside world when you are doing your work in a very secular way?

A long project like the Islamic Art gallery happened over a period of time and lots of things happened in the outside world. We were working in the post-9/11 setting in New York City.

When you deal with a collection that gives you 1,400 years of perspective, you realise that your own moment is just a moment in the much larger story. And keeping a distance from everything is important.

We had to keep the normal world away.

But in presenting it to audiences you have to engage with the outside world. They are coming with their prejudices and trigger points. At that time we did visitors' surveys, educated ourselves with what the public thinks of the word 'Islam' and their idea of the connection between the Islamic world and the objects we were displaying.

In your little way, you are changing one person at a time. That's what a museum hopes to do, right?

Our work is not rooted in any ideological idea. There is no greater point we are trying to make other than to present the art in a historically accurate and a sincere way.

In fact, one of the things that comes up about India is the whole idea of India. In this period, for example, the identity we put on is a facet of Indian history. Because we are Indian right now, and for us India exists. But in their time the idea of India that we take for granted didn't exist.

But yes, we do want to convert one person at a time to the love of art.

The show will not be able to go elsewhere?

Alas, no. I would have loved for this show to go to India, for example. There was some interest from other museums. But we are happy to just do it here in one venue.

Can you explain to me the thought that went behind the words 'Opulence' and 'Fantasy'?

Can you explain to me the thought that went behind the words 'Opulence' and 'Fantasy'?

They were very opulent. The fantasy has to do with the otherworldly quality to Decanni art -- whether it is the palanquin with golden lotuses rising out of the river or whether it is monsoon skies in the painting on the cover of the catalogue.

The fantastic element in Deccan art is very important.

The portraits are quite different from the Mughals. Mughal painting is rooted in logic and naturalism. The concept of a portraiture observing a human face emerged out of the Mughal world.

We also come up with subtitles that will make the public come in. We have to assume that they don't know anything about the Deccan.

Image: Navina Haykel: Photogragph: Dev Benegal.