'Unquestionably, the spirit behind the Panchsheel agreement and the 'Hindi Chini bhai bhai' slogan were thrown overboard by the Chinese, and a trust deficit was injected between the two nations.'

A revealing excerpt from General J J Singh's The McMahon Line: A Century Of Discord.

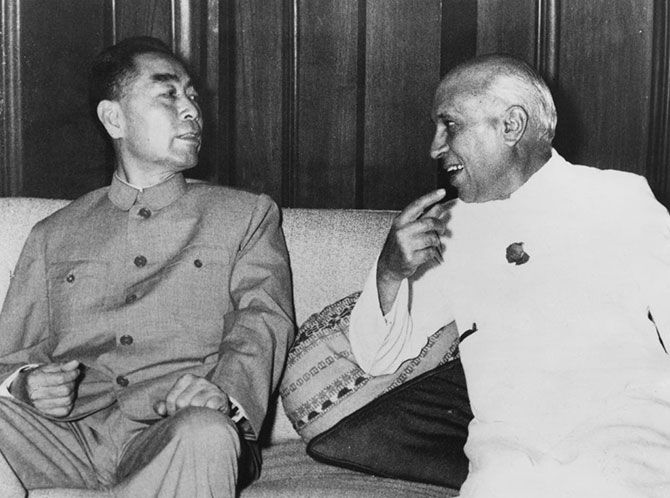

Prime Minister Nehru's visit to Peking in October 1954 was the first landmark visit of any Indian national leader to China.

The Indian prime minister was given a rousing reception and the visit was high on ceremonials.

The 'Hindi Chini bhai bhai' slogan resounded everywhere.

During this visit, Nehru pointed out the inaccuracy of the boundaries on Chinese maps.

Zhou Enlai's explanation was that these maps were reproductions of the old Kuomintang maps and that the present government had not had the time to revise them.

When the new Chinese maps published in 1956 still showed large parts of India within the Chinese boundary, Nehru again flagged the matter with Zhou Enlai during the Chinese leader's visit to India that year.

As said by Neville Maxwell in India's China War, the Chinese premier spoke only about the McMahon Line in response.

'This line, established by the British imperialists, was not fair... it was an accomplished fact and because of the friendly relations which existed between China and the countries concerned, India and Burma, the Chinese government were of the opinion that they should give recognition to this McMahon Line.'

However, unlike in the case of Burma, the Chinese did not honour their word to India.

Zhou Enlai remained consciously guarded as far as revealing the Chinese strategy on the boundary issue in the western sector was concerned, not wishing to discuss that until completion of the Aksai Chin highway, which was one or two years away!

Describing one of the fundamental features of Chinese strategy more than a century ago, the 13th Dalai Lama told Charles Bell, his biographer:

'The Chinese way... is to do something rather mild at first; then to wait a bit, and if it passes without objection, to say or do something stronger.

'But if we take objection to the first statement or action, they urge that it has been misinterpreted, and cease, for a time at any rate, from troubling us further.

'The British should keep China busy in Tibet, holding her back there.

'Otherwise, when the Chinese obtain a complete hold over Tibet, they will molest Nepal and Bhutan also.'

These are precisely the tactics the Chinese have been applying in Ladakh, Arunachal Pradesh, the South China Sea islands and other places.

It is sad that our policy planners failed to register this historical Chinese pattern of the past.

However, in June-July 2017, when the Chinese tried to ingress into the Doklam plateau (in Bhutan) near the tri-junction and build a road there, they were stopped in their tracks by the Indian Army on the request of Bhutan.

This was the first time such an action was taken by the Indian government, and the Chinese were taken by surprise.

The tense standoff continued for over two months and has been resolved peacefully for the present by diplomacy.

However, it must be noted that diplomacy works best when it is backed by military strength, as it is in this case.

Referring to a Sino-Soviet polemic in a pamphlet published in 1964-1965, Jagat Mehta (later India's foreign secretary) explains what peaceful coexistence meant to the Chinese: 'Peaceful co-existence was temporary tactics: it was not an article of faith. This fits in well with the Chinese leadership's strategy that justified the advancing of national interest by improvisation, including postponing the resolution of problems considered not ripe for solution.'

It can be recalled that even though in 1954 the Chinese were quite aware of the boundary alignment shown on Indian maps, they did not raise the matter and instead chose to conceal information regarding their construction of the Aksai Chin road.

As far as the McMahon Line was concerned, they kept their cards close to their chest.

They did not reciprocate in equal measure the goodwill and many acts of solidarity and support undertaken by India.

In addition, there was an undercurrent of rivalry between the leaders of China and India with regard to who held the pole position amongst the Afro-Asian community.

Because of their opposing ideologies, there were bound to be contradictions and differences in their approach to the same goals.

'A successful and democratic India, which rises fast and eliminates its poverty in a reasonable period, is the biggest challenge to the legitimacy of China... The competition between India and China is, therefore, an ideological one,' argued K Subrahmanyam, a noted strategic thinker and author (External Affairs Minister Dr S Jaishankar's father).

When India had published new maps in 1954 delineating its boundary with the Tibet Autonomous Region, clearly showing Aksai Chin as part of India and the McMahon Line as the international border in the east, the Chinese had not protested.

They very well knew their western highway from Sinkiang to Lhasa via Rudok was transgressing through Indian territory.

But they chose to lie low as it was not the appropriate time to raise the matter.

Later, in December 1958, when Zhou Enlai was asked to comment on the McMahon Line, he replied that it was British imperialism that had established the line, but that since it was an accomplished fact and because of the friendly relations that existed between India and China, he was prepared to give provisional recognition to the Line.

Zhou said they had not consulted the Tibetan authorities on the matter yet but proposed to do so.

This was another instance of the Chinese taking our leadership up the garden path.

When the Chinese completed the road connecting Sinkiang with Tibet, they broadcast the news to the world with much fanfare on October 6, 1957.

As soon as weather conditions permitted, Indian patrols were dispatched during the summer of 1958 to verify whether the highway traversed Indian territory.

They encountered Chinese frontier guards.

A patrol of ours, overwhelmingly outnumbered, was forcibly detained.

A second Indian patrol was able to return safely on completion of its mission.

The existence of the road, and that it traversed about 160 kilometres through Indian territory in the Aksai Chin area, was confirmed by the patrols.

They reported that the area itself appeared to be under Chinese control.

The mystery as to why our mission in Peking and the Government of India remained unaware of the planning and construction of this strategic road over a period of four to five years, from 1952 to 1957, remains unresolved.

Quite a few key personages of the time, including B N Mullik, then director of the Intelligence Bureau, and S S Khera, then cabinet secretary, have written about China's construction activity of this road being known to the Indian government and other agencies concerned from 1952 onwards.

Clearly, adequate concern was not shown by the decision makers, and this information was kept under wraps.

As a matter of fact, D R Mankekar has stated that the Indian defence attache in Peking, Brigadier S S Mallick, had forwarded a special report on the construction of the road through a reluctant ambassador, R K Nehru (who perhaps did not wish to displease the prime minister!), in April 1956, in addition to a routine report he had made five months earlier.

This report did create some alarm in the corridors of power in New Delhi, but only for some time.

In fact, the response of the stakeholders to this strategic development was grossly lackadaisical and irresponsible.

This road was undoubtedly a vital north-south artery along the western periphery of the extended Chinese empire.

The new republic sorely needed the ancient caravan route to be upgraded into a motorable road in order to transport the military resources, men and material from Sinkiang to Rudok to consolidate their hold on western Tibet.

How many more reports may have met with a similar fate or may have been concealed from the public gaze so that certain individuals or organisations could save face is the question.

How, then, can we expect to learn the right lessons from history?

It was reasonable to expect that India could at the very least have demanded a strategic quid pro quo.

China should have been made to pay a price, but instead it managed to stage a fait accompli and get away with it.

On China's completion of the road, all India did was to lodge a diplomatic protest!

Without any doubt this was a serious breach of faith on the part of the Chinese, who chose to unilaterally and secretively execute the project and claim the territory over which the road lay.

Surprisingly, Nehru did not inform Parliament until August 28, 1959 about this Chinese road-building activity, their physical occupation of our territory, the patrol clashes and other incidents.

'Without our knowledge they (the Chinese) have made a road,' said Nehru -- which, as mentioned earlier, is not entirely true.

Unquestionably, the spirit behind the Panchsheel agreement and the 'Hindi Chini bhai bhai' slogan were thrown overboard by the Chinese, and a trust deficit was injected between the two nations.

This quiet acceptance of the state of affairs by India certainly emboldened the Chinese and exposed Indian weakness.

In view of the situation, it should have been clearly realised by our leadership that the armed forces needed to be beefed up and their capability to defend the border raised many notches, commensurate with the emerging threat.

Unfortunately, this did not happen, as Nehru and (then defence minister V K) Krishna Menon did not heed professional military advice.

They chose to be guided by the miscalculations of some diplomats, bureaucrats and intelligence agencies, or went by hunch or gut feeling, or, as they did later, by the advice of pliant and incompetent generals.

Excerpted from The McMahon Line: A Century Of Discord by General J J Singh (retd), with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.