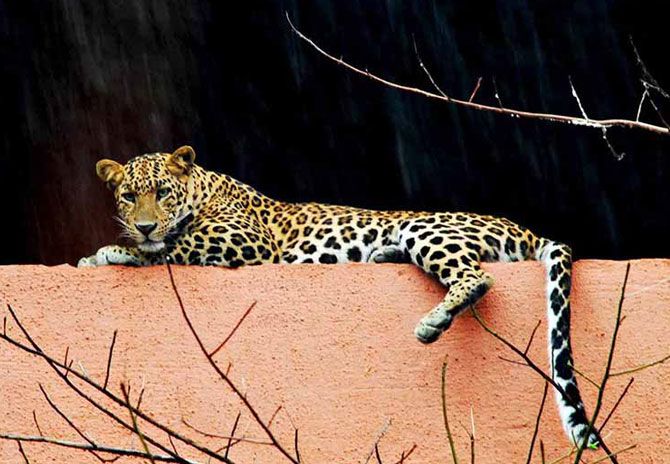

Can humans and leopards co-exist in Mumbai?

Rediff.com's Rajesh Karkera explores why news about leopard sightings within Mumbai have become more common and why it is NOT a threat.

Leopard enters Mumbai housing society, carries away dog...

Caught on CCTV camera: A leopard crossing street in Mumbai...

Dog chases leopard away from housing society...

Leopard menace in Mumbai...

Politician orders shoot at sight for leopards...

These are just a sample of headlines pouring out of Mumbai in recent months.

But the problem -- the man-leopard conflict in the city -- is not a new one. It is just one that has intensified as Mumbai's population has exploded.

But what is a scared city dweller to do when s/he comes face-to-face with a leopard?

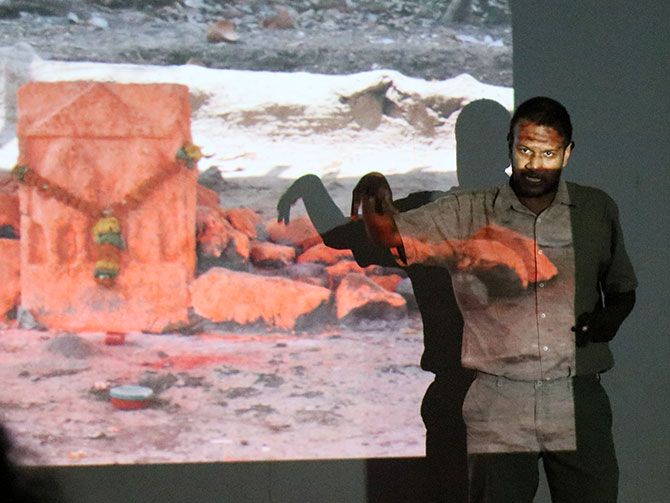

This is where Mumbaikars for Sanjay Gandhi National Park (MfSGNP) comes in.

An initiative of the Maharashtra forest department, the group is made up of volunteers from different fields.

Their job is to assess the conservation status of the leopard -- the only large cat found in Mumbai and neighbouring Thane -- and mitigate the human-animal conflict in and around the national park.

It does so by involving the people who live in these areas and educating them.

What exactly is the conflict?

"We humans, when we see any wild animal in the open, right in front of us, in 'our' space, we call it a conflict," explains Sunetro Ghosal, an MfSGNP member. "We need to understand that spotting a wild animal in your backyard is not a conflict. It is merely an interaction. Especially here in Mumbai where you are staying in close proximity to a national park!"

"Leopards are very adaptive, but also very shy," says Ghosal. "They will avoid people as much as they can. A leopard could be living next to you for your whole lifetime. You won't know."

So, what is it that makes them wander into places overrun by humans?

Only the basest of animal instincts: Hunger.

"Dogs are a delicacy for them. It is the most delicious food now available to them in the peripheral areas of the national park," explains Ghosal. "It is this food that makes them come inside our society walls, which we have built inside their territory."

"For the leopards this is their territory. No walls or fences can keep leopards away; they are very sharp and smart," Ghosal adds.

"They will look for food only around this imaginary territory of theirs. They will not wander out of it."

"It is we humans who have encroached on their territories, Ghosal points out. "We have been lured by money-making builders with promises of greenery and (views of) serenity from our windows."

"We -- who have made our homes in such close proximity to the national park -- forget, that with the forest (and serenity), will come its inhabitants too. We forget that without those inhabitants, there would have been no forests in the first place!"

Why do interactions between Mumbaikars and leopards lead to bloodshed?

"You spot a leopard in your society. You panic. A crowd gathers. That crowd stones the animal and injures it. It gets even more scared. In an attempt to get away from the angry crowd, it may hurt people grievously," says Ghosal. "Or you call us to capture it."

Till some time ago, when the latter happened, the forest department felt that the leopards needed to be captured and released in a wild area.

But that was not how it works, they slowly discovered.

"Suppose there is a family of five leopards living near your area," Ghoshal explains. "Remember: That area is marked by your building wall as your area is the boundary for YOU. Not for the leopards."

"They already have an imaginary territory, which they normally would not go out of. It is actually your new building, which is now inside or in the periphery of that territory of the leopard."

If one of a family of leopards is captured and relocated, he continues, there is space for one more leopard both in terms of food and area.

"That space of THAT one leopard becomes free. And just like for human habitats, in Mumbai, when one house/land becomes free, within a few months, if not weeks, someone new comes to live there, removing a leopard might bring a fresh, younger one or even two."

"You were safe previously because the older animal knew its timings and boundaries," he adds. "It knew after dark when no humans are around it can come and hunt for food. It knew not to come out and wander in the day."

But the newbie leopard hasn't figured all this out and times have changed. They smell dogs and, being young and rash, go for the kill.

And thus starts the conflict.

It is a phenomenon seen all over the world, says Ghoshal.

According to him, between 1991 and 2005, leopards were either trapped or killed every time there was conflict. "And every time we caught/trapped and moved an animal the conflict would later only increase."

Based on studies conducted by experts all over the world, forest departments in India stopped trapping animals since 2005 unless the conflict situation was really bad.

And over time -- especially after 2013 -- Ghosal says the conflicts between man and leopards in Mumbai have actually decreased.

But what about the headlines?

What about the popular belief that leopards are increasingly straying from SGNP?

"Nowadays," says Dipti Humraskar, wildlife biologist and member of MfSGNP, "it is only because of CCTVs, social media and television channels who want to sensationalise news, that you see these leopards as threats."

"All they (the leopards) do is what they have been doing for ages -- they come looking for food when hungry. And go."

"Most of the times leopards take cover of the dark. Or (come) early morning /late evening. For all these years, leopards were always around. But people didn't know. The animals avoided them."

Humraskar says it was certain over-publicised stray incidents that put the focus on leopards.

At Royal Palms in Goregaon, north west Mumbai, a leopard walked past somebody's balcony.

At Ekta Meadows in Borivli, located too close to the park, people looked out of their window and saw a female leopard near an abandoned structure playing with her two cubs.

These and a few other sightings, Humraskar says, were routine, but got hyped when videos were circulated: "The residents of the society where the dog-versus-leopard conflict happened, were quite aware of the leopards living in their midst and of the leopard visits. They had not complained, but someone uploaded footage on social media and the television channels got hold of it."

"Seeing a leopard is NOT a conflict. It's like seeing a stray dog," she adds. "You see it and walk away."

"When a stray dog is threatened it starts barking and can attack. It is the same case with a leopard. They will either hide or just wait for you to pass or you can stop and give them (right of) way."

"This is more of an interaction. Not a conflict."

Humraskar also points to extensive studies that have shown that most leopards prefer to stay inside the park: "Remember animals don't stray like humans. They tend to be in and around their own territory."

And the park has enough food options for a leopard by way of deer.

Noting that a domesticated dog living in close proximity to humans is unlikely to be attacked by a leopard, she adds that leopards living in the peripheral areas of the park step outside only because "we humans have littered up our surroundings, attracting stray dogs, pigs and rodents."

Can Mumbaikars co-exist with leopards after all?

Both Ghosal and Humraskar believe it is the new residents who have come to stay in buildings near the park, "by paying a premium," feel leopards are a threat.

"After seeing one," Humraskar says, "they contact local politicians. Politicians have their own agenda to be in the limelight and give out statements like: Shoot on sight for leopards."

"Trapping or killing leopards is not a solution. It is more about us. It's not about the leopards. We need to change our biases and perceptions. We have to build acceptance."

"We can't think like: The animal should stay in his area. Why is he coming to mine? Why is he coming to drink water from my swimming pool?"

Man, she adds, has been living with large carnivores from the beginning of time. When they are exterminated, like they were in Europe and America, one has to pay billions to bring them back into an ecosystem.

"Native Warli tribals live inside the park," Ghosal says. "They worship Waghoba (the tiger god) and consider them to be the ones who watch over the well being of the tribals. These villagers have been living with these leopards. They don't seem to have any problems with them being around."

How do we stop leopards from hunting outside the park?

It is actually very simple. Grass.

The connection is a bit circuitous.

"We have the highest density of leopards here (compared) to all national parks in the world. We have 35 documented leopards in an area of 104 square km," Yatin Gholap, a botanist at SGNP, explains.

"When we consider the high density of leopards here, we need to understand that there needs to be enough food for the leopards here in the park itself. Those are the herbivorous animals," he adds.

"There are ample tree species here inside the park. But these can't really be food for those herbivorous animals. These animals are actually hunting for herbs and shrubs inside the park. The most promising food they can find is grass."

But India lacks grasslands, especially dedicated grazing lands.

So, the Indian forest department is working with experts to try its best to grow grass that Indian herbivores will enjoy.

Plans are on to convert the land around Tulsi lLake (which is Mumbai's second largest potable water lake) in the park to grazing grasslands for herbiovores.

"Setaria is one of the grasses that we, with the forest department's help, are growing," says Gholap. "It is a palatable grass that is the food of deer and all the herbivorous animals."

"When (herbivores) grow well and their population increases, there is enough food for the leopards. That will take care of the cycle of life inside the park."

"When there is ample food available inside the park itself, why the hell would the carnivores, namely leopards, stray away from the park?"