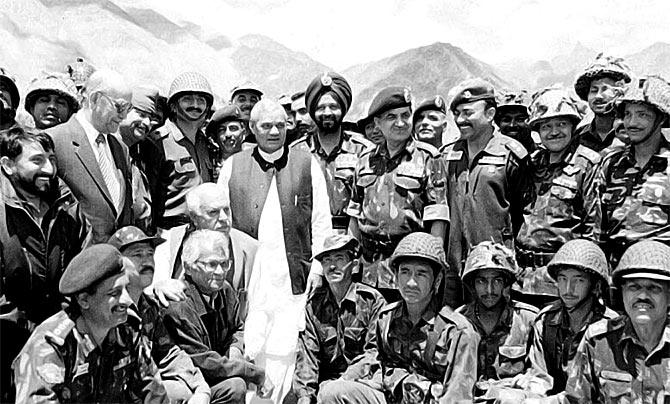

Vajpayee had always felt that India must act with conviction and panache.

He decided that, irrespective of the attendant risks, he would undertake what many felt was a precarious course.

A fascinating excerpt from N K Singh's Portraits Of Power: Half A Century Of Being At Ringside on Atalji's 96th birthday, December 25.

'I dream of an India that is prosperous, strong and caring. An India that regains a place of honour in the comity of great nations.'--

Atal Bihari Vajpayee

Atal Bihari Vajpayee was, in some ways, unique in our political firmament, in that he had taken the oath of office of the PM three times. First was a term of 13 days in 1996; second, for a period of 13 months from 1998 to 1999; and third for a full term from 1999 to 2004.

There are several aspects of the Vajpayee era that would be remembered in multiple ways. The most important, however, was India's consolidation as a nuclear power.

Vajpayee had been an advocate of embracing nuclear weapons as a step towards a superpower status.

He had always felt that India must act with conviction and panache.

In the end, the world respects the strong, and harping on the philanthropy and compassion of countries does not enhance its standing in the comity of nations.

He decided that, irrespective of the attendant risks, he would undertake what many felt was a precarious course.

Earlier PMs had considered this option, but were talked out of it given its implications of inviting severe sanctions against a country whose balance of payments remained fragile.

Political and economic sanctions have serious consequences for macroeconomic stability, standing in international organisations, access and cost of foreign capital and growth.

We in the ministry of finance had, in an earlier period, evaluated the economic consequences. The political leadership had then recognized its significant economic fallout and walked away from exercising this option.

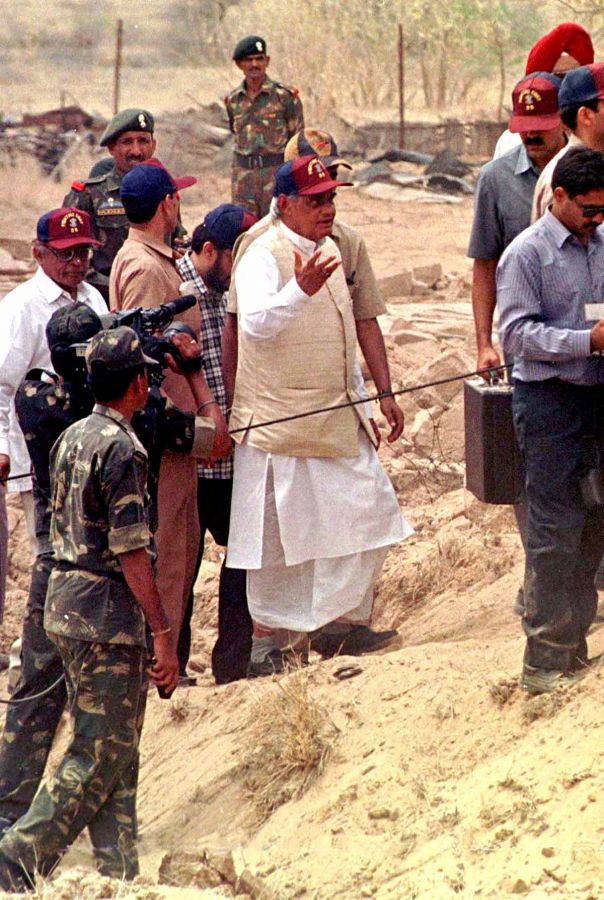

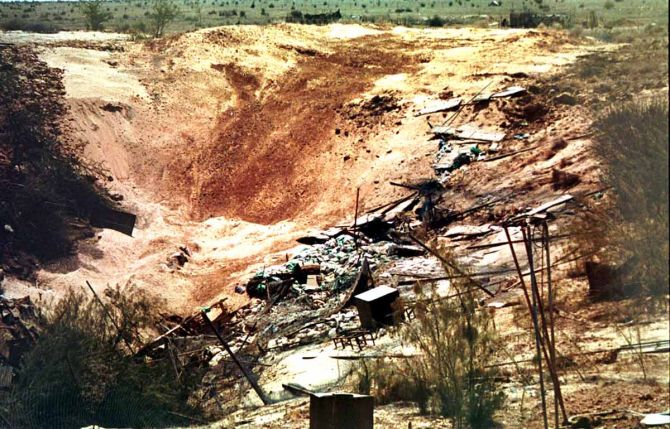

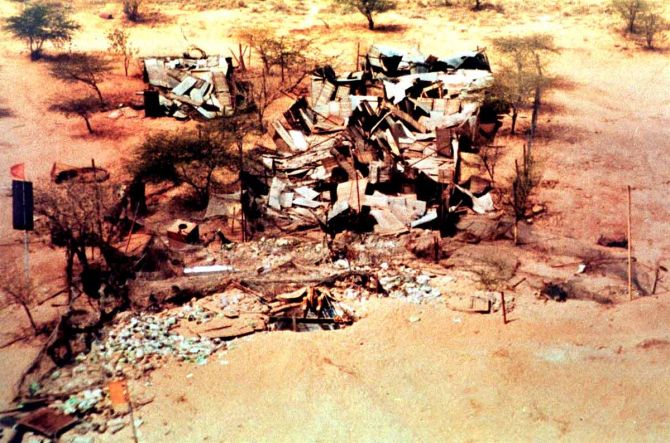

On May 11, 1998, Vajpayee took an audacious though risky decision.

The NDA government on that day conducted three nuclear tests in the desert of Pokhran, followed by two more just two days later on May 13.

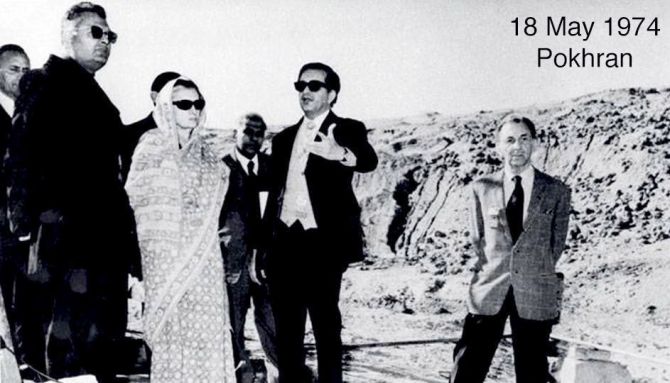

This was exactly the place where India had first conducted nuclear tests on May 18, 1974.

The decision-making process was a closely guarded secret between the PM, the NSA and the concerned ministries; even those working in the PMO did not have an inkling of the ensuing events.

Following Pokhran-II, Vajpayee unilaterally declared India to be a nuclear weapon State and added that India would demand acceptance as the sixth nuclear power. His statement said, 'India is now a nuclear weapons State with a capacity for a big bomb.'

Several commentators advanced various arguments in support of the Indian position.

It was argued that the first nuclear tests were conducted in the background of perceived security threats in India's neighbourhood, which included China and Pakistan. Notwithstanding changed circumstances, these threats had only magnified.

The Non-Proliferation regime and the absence of total global disarmament led different nations to brandish the use of the term 'nuclear currency' frequently in international discourse, and India being a non-signatory to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was now exercising this option and its rights over this currency.

He did, however, simultaneously announce that this was only in self-defence, and also committed to the principle of 'no first use'.

Vajpayee set up an informal group under his chairmanship, which, for the first 10 days following the nuclear explosion, held daily review meetings in his South Block office to assess the economic and political consequences of the decision.

The PM, foreign minister and, of course, the NSA played a proactive role in structuring these daily meetings. Reports received from foreign missions and other analysts were discussed.

Both Montek (Singh Ahluwalia) as finance secretary and I as revenue secretary participated in the first 10 days of this informal crisis management group.

The American reaction was as expected. It was hostile, with President Clinton himself condemning Pokhran-II outright: 'I want to make it very, very clear that I am deeply disturbed by the nuclear tests which India has conducted. The United States strongly opposes any nuclear testing.'

In an obvious reference to economic and military sanctions, he said, 'Our laws have very stringent provisions, signed into law by me in 1994', in response to nuclear tests by non-nuclear States.

He added, 'I intend to implement that fully'. He also announced that economic and military sanctions would be imposed on India under the Arms Export Control Act.

The sanctions would stop US development assistance to India, which, at that time, amounted to a somewhat meagre $140 million, but, more importantly, it would debar foreign assistance, foreign military sales, export financing, government credits, credit guarantees and other financial arrangements including those supported by the Export Import Bank, except private bank loans.

It also barred any US support for financial assistance including those from international financing institutions like the World Bank, IMF and International Development Bank (IDB), and also subjected some private companies in India to debilitating sanctions.

The sanctioned Indian categories included the department of atomic energy, Defence Research and Development Organisation, entities of the department of space and a clutch of private firms that worked with them.

Understandably, like the US, many other allies like Japan also imposed economic sanctions.

Japan was particularly sensitive, having undergone the trauma of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from nuclear weapons during the World War; they had an emotional attachment to nuclear non-proliferation.

While France and Russia remained unaffected by the nuclear experiment, the UK realised it had long-term trade and business interests and just reacted strongly.

Instead of supinely accepting these sanctions, Vajpayee actively encouraged diplomatic engagement, re-energised Indian missions abroad to explain India's point of view and initiated discussions at multiple levels.

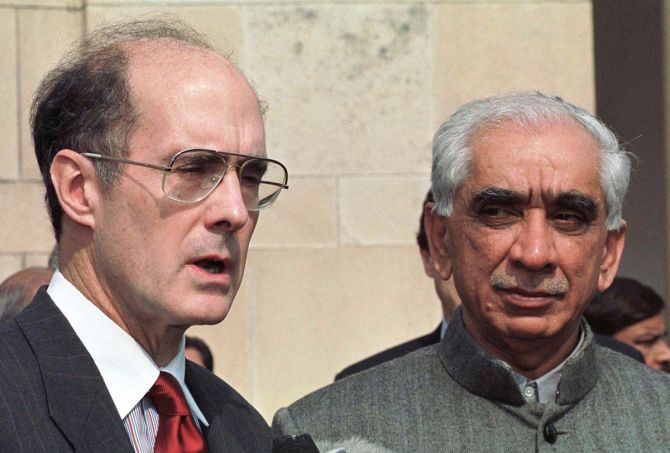

From June 11, 1998, diplomatic negotiations commenced with the Indian side represented by Jaswant Singh, deputy chairman of the Planning Commission and later the foreign minister; and the US side by Strobe Talbott, deputy secretary of state.

The Talbott-Jaswant negotiations were held in seven countries and 10 cities, and included 14 rounds. These talks, conducted with expected secrecy, remained somewhat unstructured and the outcomes at that stage were unpredictable.

Following these intensive negotiations, the areas of differences had narrowed down to four major issues: CTBT, NPT, export control and overall defence budget.

Vajpayee himself said, 'I have been in regular correspondence with President Clinton. Our correspondence has touched not only upon issues under discussion between our representatives but also larger aspects of (the) Indo-US relations. It is my view that the future of Indo-US relations is much larger than the four issues under consideration.'

As a consequence of these negotiations, India offered a voluntary moratorium on nuclear explosions after May 1998 and a ban on the production of fissile material. It had, therefore, effectively accepted the Fissile Material Cut-off Treaty (FMCT) in principle without signing the agreement.

Talbott has himself written about these negotiations in his book, Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy and the Bomb.

India weathered the onslaught of these debilitating sanctions, somewhat scarred but in no way grievously injured.

Talbott wrote in the conclusion of his book, 'I hope my regard for the way Jaswant Singh advanced his nation's interests and sought, as he put it, to harmonise US-India relations speaks for itself in these pages.'

These words are a testament to Jaswant's skills as much as to Vajpayee's leadership. He had a modern frame of mind and never allowed political ideology to stymie what he believed would be in the country's larger interest.

Vajpayee left a lasting imprint on our foreign policy, and was instrumental in ushering a new era in Indo-US ties.

By 2000, the tension generated by the Pokhran tests had eased. The broad concept and tangible steps had featured in the Jaswant-Talbott talks. All this resulted in the first US presidential visit after 22 years (since President Jimmy Carter's visit in 1978), which came less than two years after the nuclear explosion.

As part of a preparatory delegation, the secretary of the treasury, Larry (Lawrence Summers) came to India and met Vajpayee during his visit between January 17 and 19.

President Clinton was to visit two months later in March of that year.

There was an interesting incident relating to the visit of Larry when he called on the PM in his office.

Just prior to the meeting, Vajpayee wanted to be briefed on the likely conversation between him and Larry.

I had carried a copy of a cover story in Time, which had the photographs of Robert Rubin, Larry and Alan Greenspan as the three people responsible for the prolonged economic buoyancy in the US.

I explained to Vajpayee that from among these three people, one of them -- Larry -- was going to see him very shortly.

When Larry went to see him, he asked the understandable question of what Vajpayee's expectations were from the Clinton visit.

After a pause, Vajpayee replied, 'To further and deepen Indo-US relations.'

Larry then posed the next question to Vajpayee: 'As prime minister, what is your great vision for India?'

Vajpayee, after some hesitation, replied, 'To eliminate poverty and improve life quality, education and health.'

Larry being Larry pushed Vajpayee further and asked, 'How do you expect this objective to be achieved?'

At this point, instead of responding immediately, Vajpayee went into thinking mode.

There was hushed silence in the PM's room where every second matters a lot and seems as if an enormous amount of time has elapsed (there can be no prompting in a conversation where there are only four people: The PM, Larry, the US ambassador and I).

The pause became longer with every second.

Vajpayee finally responded by saying, 'You tell me. You are, after all, the Magic Man.' He had, in his mind, translated the picture in Time magazine of the three people responsible for prolonged US prosperity and used the beautiful expression 'Magic Man' in that context.

Larry was profoundly grateful for receiving this compliment and the meeting ended on a happy note.

Larry, thereafter, decided to drop into my room and kept the ambassador out.

He asked me, 'Did I do something wrong because the prime minister took a long time to respond to my questions, and thereafter, his responses were precise though somewhat brief?'

I told Larry, 'He wanted to listen to you instead of talking himself. After all, he had called you the 'Magic Man'.'

Larry clapped his hands with joy and said, 'I knew there was something wrong. This ambassador had briefed me that, 'Larry, you speak too much. We don't want to listen to you. We want to listen to the prime minister.' And that is why, NK, I had kept quiet to the prime minister's suggestions that as a 'Magic Man' I should have all the answers.'

It was not as if Vajpayee did not have a response, but such was his faith and belief in the power of words that he would, in his mind, seek to translate his thoughts into the most appropriate words in English. This sometimes took time.

His pauses were not lack of understanding. It was his quest for perfection in the use of the most suitable words.

Vajpayee, often condemning the harsh remarks from critics -- while also recognising that it is their right to criticise him -- used to say, 'Kin shabdo ka unhone prayog kiya hai (Just look at the words they have used).'

It was not so much the criticism that he resented, but the words used.

Excerpted from Portraits Of Power: Half A Century Of Being At Ringside by N K Singh, with the kind permission of the publishers, Rupa Publications India.