'The Hindu quest for political power in terms of a Hindu identity can pose a problem for tolerance, as the alignment of religion with power often does.'

A revealing excerpt from Arvind Sharma's Religious Tolerance: A History.

The establishment of British Raj over India created a new context in the history of Hinduism, which had major implications for the attitude of Hinduism toward other religions.

While the major tendency within Hinduism in the Medieval period was exclusivistic in a social and religious sense, it became markedly inclusivistic and pluralistic after its encounter with the West through British rule.

Many factors played a role in producing this outcome. One of them was the impact of Christianity, which produced far-reaching direct and indirect results. One direct result was exclusivistic, in terms of religious identity, in two ways.

Hinduism tried to defend itself against Christianity as it had done against Islam.

This reaction involved, 'the outright and hostile rejection of the values and ideas of the Western World [and Christianity]. This response must have been fairly widespread, and even though it did not receive literary form until late in the nineteenth century, it was an important element in the Mutiny of 1857.'

Many causes led to the Mutiny but, 'there can be little doubt … that the general cause was the distrust awakened by the rush of social change initiated by the British and that this took the particular form of a fear that the changes presaged an attempt by the British to convert the people to Christianity.'

This exclusivistic trend was further manifested in the post-Mutiny period by the attempt to introduce 'conversion' into Hinduism by a process called suddhi, which involved reconverting those Indians who had converted to other religions such as Christianity, back to Hinduism.

It is, of course, possible to interpret this as an inclusivistic trend from a certain point of view, but as we shall soon see, Hinduism developed a self-perception of being a tolerant and non-proselytising religion during this period; from such a perspective, this attitude may be judged exclusivistic.

Moreover, when British imperialism gradually provoked a counter response in the form of Indian nationalism, then one strand in it tried to define Indian identity in terms of Hindu identity, which also acquired exclusivistic overtones, associated with the concept of Hindutva.

The more pervasive response of Hindu tradition to Christianity was in a somewhat different key.

Crucial to understanding this is the realisation that Hinduism began to acquire self-consciousness of a kind which it had not possessed earlier, from around c. 1800 onwards.

And in this, its perception of itself as a tolerant religion became a crucial element.

Almost all the major spokespersons of modern Hinduism were open advocates of religious tolerance and religious pluralism.

This Hindu self-perception predates the rise of the national movement for Indian independence, which drew support from this aspect of modern Hinduism for both idealistic and practical reasons, thereby strengthening it all the more.

The appeal for religious tolerance embodies an idealisitic aspiration, but it also coincided with the need for the followers of all religions found in India to present a joint front against the British.

This was the prevailing ethos of the country until the 1930s, after which the Muslim community in India broke rank with it sufficiently for Pakistan to be formed.

However, throughout this period, and even today, the overall attitude of the Hindus (with some aberrations provoked by the creation of Pakistan) has been the reverse of the Hindu-Muslim Mexican standoff during the Medieval period; the encouragement of mutual accommodation of the two communities, rather than their separation, is the primary orientation.

Our ends are perhaps better served by interrogating whether Hindu tolerance during this phase is inclusivistic or pluralistic in nature.

The fact that most Hindus tend to assume that it is pluralistic in nature while many non-Hindus tend to identify it as inclusivistic, adds further interest to this inquiry.

The setting for this debate is best provided by Swami Vivekananda's oration at the World's Parliament of Religions in 1893, delivered on 11 September to its 6,000 delegates who had assembled at Chicago.

Richard Davis analyses the textual citations in Vivekananda's speech and concludes that both of them are suggestive of inclusivism rather than pluralism, and after enlarging his analysis to include texts of a Saiva sect such as the Saiva Siddhanta, along with the Vaisnava text, the Bhagavadgita, concludes that although, 'Krishna in the Bhagavad Gita and Siva in the Saiva Agamas instruct Hindus to accept all religions as true and valid for those who believe and practice them; but, at the same time, they hold that one religious viewpoint is still truer and more efficacious than the rest.'

In other words, Davis argues that Swami Vivekananda overstates the case for Hindu tolerance. Is this the case?

Vivekananda was a disciple of Sri Ramakrsna Paramahamsa, so it may not be irrelevant to compare Swami Vivekananda's concept of religious tolerance with that of his Master, to determine the extent to which he was representing his Master's position on the point.

Scholars have pointed out that a difference emerges when a comparison is carried out on issues of religious tolerance, religious pluralism and universal religion between the views expressed by Swami Vivekananada and the movement he founded, namely, the Ramakrishna Mission, and those of Ramakrsna himself on these matters.

If the teachings of Ramakrsna may be reduced to the motto 'Individual preference but no exclusion', the teachings of his disciple Vivekananda may be reduced to the motto 'Advaitic preference but no exclusion.

In other words, in the context of modern Hinduism, the attitude of Ramakrsna may be described as pluralistic while that of Vivekananda may be described as inclusivistic.

The almost idealised vision of Hindu tolerance, which Mahatma Gandhi incarnated in his person, received a serious reality check with his assassination on January 30, 1948, which embodies two curious paradoxes.

Pakistan, as a homeland for the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent, came into being in 1947 partly on the ground that the Hindus were not sufficiently tolerant of Muslims, while Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948 by a fellow Hindu on the ground that he had been too tolerant of Muslims.

This is the first paradox; the second paradox is that both Mahatma Gandhi and his assassin N Godse believed in an undivided India and were equally opposed to Partition, yet one ended up assassinating the other.

The resolution to this paradox requires the introduction of a new word Hindutva, a word coined in 1923 by V D Savarkar, who, contra Gandhi, believed in a more muscular approach to national issues epitomised in the motto 'Hinduise politics and militarise Hindudom.'

This emerged as the more extreme position on the role Hinduism was to play in Independent India, often referred to as Hindu nationalism.

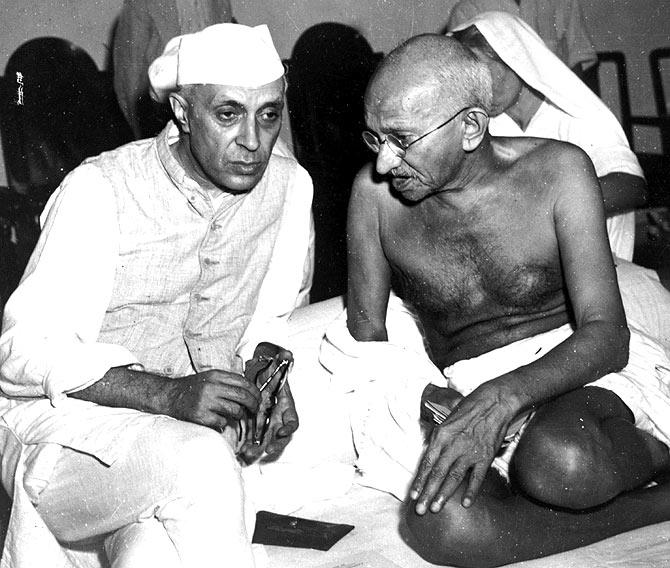

The mainline position was represented by the views of Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru.

These two collaborated closely in the non-violent Indian struggle against British rule but had different views on the role of religion in public life.

Gandhi was a religious pluralist, who also felt that religions had a positive role to play in public life.

He was nevertheless committed to secularism in the sense that the State should not be aligned with any one religion and thus believed that India should be a secular state.

So did Nehru, but Nehru was also more inclined to be secular in the European sense of the word, which associates it with a secular rational outlook and looks askance at the role of religion in public life.

Gandhi's position remained dominant from the 1920s until his death, after which it was replaced by Nehru's vision of the role of religion in national life, which was also enshrined in the Indian Constitution.

Three strands can thus be identified on the question of the relation of religion to Indian nationalism, once it started to assume distinct shape after 1920, when the struggle against British rule commenced in right earnest.

According to one view, associated with Savarkar, which remained a minority view for a long time, Hindu religion or culture -- understood as a code word for all the religions of Indian origin (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism) -- was to be the primary element in shaping it.

According to the second view, associated with Gandhi, it was to be shaped by India's religious pluralism, as represented by all the religions found in India.

According to a third view, associated with Nehru, Indian nationhood would avoid any connection with religion as far as possible, except in a reformist capacity.

These three positions assumed prominence in different phases of modern Indian history: The view associated with Gandhi was most influential from the 1920s until 1948, after which the view associated with Nehru became the major influence, and came to be associated with the Indian National Congress, which he led until his death in 1964 and which remained India's dominant political party well into the 1980s.

During the past few decades, however, the worldview of Hindutva as represented by the Bharatiya Janata Party has made political gains and poses an increasingly serious challenge to the Indian National Congress and its worldview.

This historical perspective is necessary to understand the state of religious tolerance in relation to Hinduism in our times, because it is shaped by the role these three positions came to occupy in Indian politics.

Once again we have here an example of how the virtually unqualified religious tolerance of Hinduism when it had no political power, becomes subject to stresses and strains upon contact with political power.

It is worth noting, however, that none of these three positions compromise Hinduism's soteriological pluralism in the least; nor do the three positions call into question the idea of India as a secular State although they might debate the best understanding of it.

Nevertheless, the rise of Hindu nationalism does complicate the question of religious minorities in India.

The Gandhian and Nehruvian positions were liberal to the point of granting more Constitutional rights to the minorities compared to the majority, to enable them to feel safe in a Hindu-majority country, but Hindu nationalism is in favour of treating all religious communities strictly on par in its urge to make the national prevail over the 'communal' (a term used to designate sub-national religious identities).

In this sense it is even more secular in its position compared to others, whose stance it thereafter brands as pseudo-secularism.

This is, however, also accompanied by a sense of being a 'persecuted majority', which sometimes finds violent expression -- as in the demolition of the Babri mosque in 1992 in Ayodhya -- much to the consternation of the minorities and moderate Hindus alike.

How are we to assess these developments in terms of religious tolerance in the context of contemporary Hinduism?

Although Hindus have historical grievances against the Muslims and Christians who ruled over them in their own country, the Hindu self-perception of being a tolerant religion had, by and large, kept militant Hindu tendencies in check.

Hinduism has hitherto enjoyed and cultivated its reputation for tolerance and even insisted at times that tolerance is not merely a characteristic of Hinduism, but constituitive of it.

If two Hindus have little in common, then it is the mutual tolerance of this diversity that allows them to participate in the membership of the same community.

Hindus tend to externalise this attitude toward religious pluralism internal to Hinduism, in their dealings with Islam and Christianity, but find it difficult to maintain it if they are made targets of overt or covert proselytization -- tolerance associated with modern Hinduism does not take kindly to proselytisation.

According to Hinduism, if all religions are valid, then it is not necessary to change one's religion, and if it is not necessary to change then it is necessary not to change.

Hindu tolerance is thus now under challenge with the rise of the Hindu Right in India over the past two decades.

The Hindu Right shares the general Hindu position on soteriological pluralism, but the Hindu quest for political power in terms of a Hindu identity can pose a problem for tolerance, as the alignment of religion with power often does.

Hinduism shares this predicament with Judaism, which like Hinduism remained apolitical for centuries. The formation of Israel, however, provided a new context for its heritage of religious tolerance to negotiate.

The rise of the Hindu Right creates a similar situation in India.

Excerpted from Religious Tolerance: A History by Arvind Sharma with the kind permission of the publishers, HarperCollins India.