'My brave JCO managed to get to the gun, sit on top of the dead man and fired away at the attacking aircraft till they melted away into the darkness.'

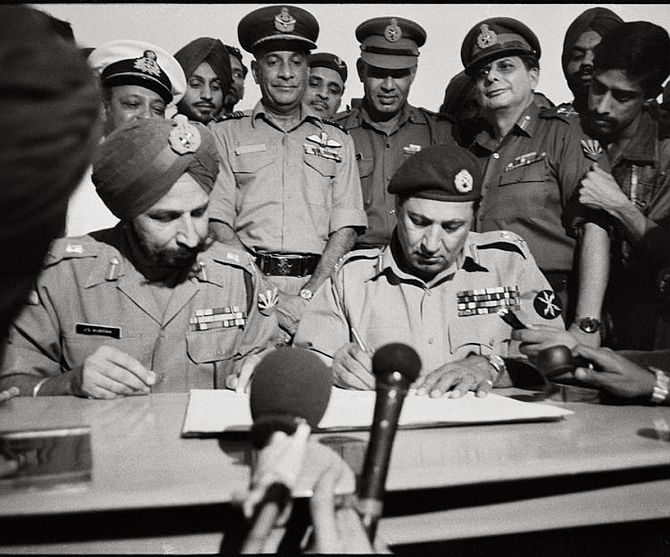

In the first of a series on 1971 War Heroes, Air Commodore Nitin Sathe recounted his memories of his father Colonel Bal K Sathe's valour in that war in which India defeated Pakistan.

In the second feature in the series, he meets Brigadier M V Gharpurey, another veteran of the 1971 War whose military triumph India celebrates today, December 16, as Vijay Diwas.

Meet Brigadier M V Gharpurey, IC 8612, now 85 years old. 'Bhau' (meaning Brother), as he is well known as, retired from the Indian Army many years ago and has settled down in Pune.

He and my dad were good friends from Artillery and I often heard dad and Gharpurey Sir taunting each other about their roles in the War of 1971.

Whilst dad was a 'Field Gunner', Gharpurey Sir was an Air Defence man.

As I was preparing to leave for my Services Selection Board interview, it was Brigadier Gharpurey who briefed me for the same.

He was intrigued why I was choosing to join the IAF and not my dad's regiment and the only words of advice that he gave me on that cold wintry day in Jammu before I left for the station were, "Go and enjoy the process of selection! I am sure that you will pass and do your dad and us proud!"

Brigadier Gharpurey has very vivid memories of the war. These are untold stories of the war and not recorded anywhere.

"In '71, I was just a major with 13 years of service and an Air Defence Battery Commander which was part of the 152 AD regiment."

Detached from his unit, he was to operate independently during the war.

With just five junior officers who were mere rookies udner his command, the task was daunting to say the least.

"By July '71, the training courses undertaken at the Deolali cantonment were stopped and officers returned to their units to augment the strength for the impending war."

"By the next month, a large number of senior officers visited the station to meet the troops and it was clear that something was in the offing."

"This along with the fact that at the political level, Mrs Indira Gandhi had paid a visit to many countries to garner support for the war made us quite sure that war was indeed a possibility soon," the veteran recalls.

Moving to the front

"There was no clarity when and where we would be headed ,but the ammunition trains started arriving in September which involved a lot of hard work."

"One day, a consignment of sand tires arrived, and we were told to change the tires of all our vehicles. This gave us a fair idea that we were headed somewhere into the desert sector. We were ordered to be ready to move at short notice and in the interim, we continued to train at our home base. One by one, units around suddenly left for unknown destinations," the brigadier remembers.

"It was soon our turn. The special train arrived and we were loaded up within two days. The first casualty of war happened during the loading. One of the men who was using a crane to load the heavy equipment was electrocuted by the overhead cables and died instantly."

"This was not a good start to the war, there was a pall of gloom when we left Deolali at night a couple of days later," he remembers. "No ladies came to see us off, but the band played some marching tunes as we chugged out of the station which made us feel a little better."

"We had a first-class bogie for just the five of us and before we knew it, we were at Bombay from where we changed to the western line and headed towards Barmer."

They reached Barmer around midnight and it was time to meet the Brigade Commander to receive orders.

His second in command came to him with a unique problem just then. His young deputy had loaded the major's entire office along with furniture and a lot of rum in one of the wagons that were of no use here in the field conditions.

"He had even got some portraits and potted plants which adorned my office in Deolali!" exclaims the old soldier, recalling that discussion 49 years ago.

The young officer had been over enthusiastic to ensure that his boss was comfortable in the field and had not realised that most of the paraphernalia was not required in war! He was promptly asked to send back the extras to Deolali where the rake was headed to get another unit.

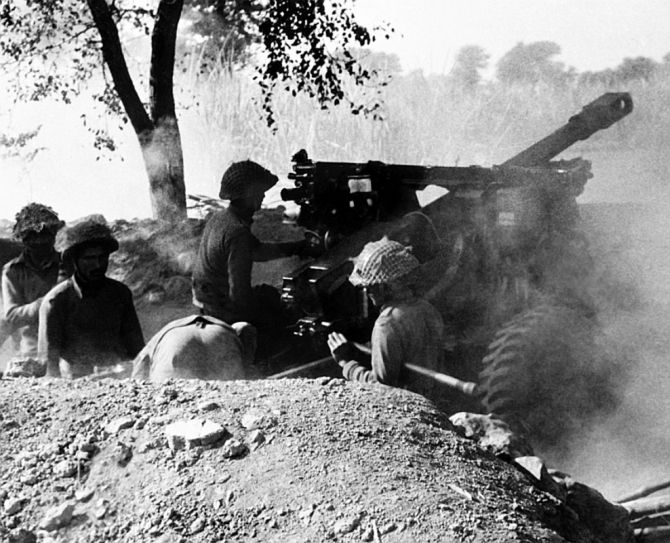

The Air Defence unit operated the vintage L/60 gun developed well before the Second World War.

Produced by the Swedish, the Germans were the first to use it during the war, albeit not widely.

It was towed by a vehicle and had a manual sight only unlike the L/70 which was radar controlled and had a better rate of fire.

"With shortage of the L/70, we had no choice but to continue use of the L/60 in the war especially in our sector. Since it was an all-manual operation, the crew had to be extremely well trained. Our crew were extremely good and integrated well as a team," Brigadier Gharpure remembers.

"We were deployed alongside the units of the 11 Infantry Division. There was no formalised control and reporting system and we had the rudimentary reports coming from forward located troops as well as through the railway communication systems. Railway station masters had been trained to pass information of enemy aircraft when seen."

"The only real information came from our own observation posts located around 5 km around our guns and this early warning was hardly adequate!"

"Despite all the limitations, my battery can boast of one enemy aircraft kill. We had taken part of the wreckage back as a memento of the war."

"Our air force aircraft were operating further north and south of where we were. So, any aircraft that ventured into our air space was enemy. Thankfully, there was no chance of committing fratricide and no problems in identification friend or foe," emphasises the octogenarian.

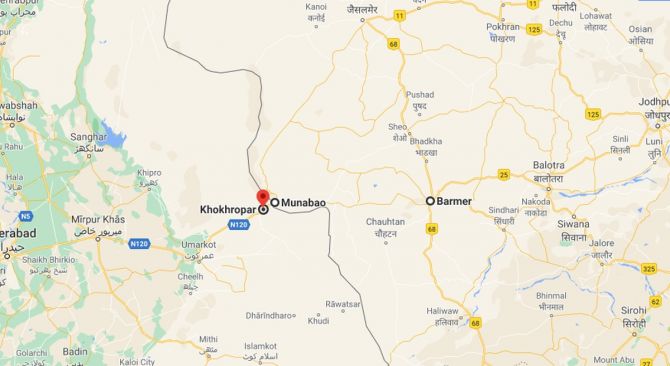

During the war, we reached almost 40 km into Pakistan on the Munabao-Khokropar axis.

We held onto the territory and the logistics was stretched to the limit. The engineers had done a good job of making duckboard tracks through the desert so that the supplies could reach us.

"Rather than using these 'duckboard' tracks, I preferred travelling in my jeep on the railway track! There was no traffic and it was interesting to stop at the small abandoned two or three stations enroute."

"One day, we decided to explore locked rooms at one of the stations during my drive to Khokhropar. I first told my JCO to look for booby traps and then got the big padlocks opened."

"We were quite surprised to find stacks of Bank of Pakistan cheque books in one of the rooms."

"On yet another journey we discovered a large number of boxes of condoms!" the 85 year old exclaims with a chuckle.

The Indian Railways had opened up the railway line ahead of Gadra Road into Pakistan and there were plans of running freight trains right up to the unit location at Khokhropar.

"I remember one afternoon when a trainload of ammunition arrived at Khokhropar. We were immediately ordered to provide Air Defence support to it should an attack materialise. And, an attack did materialise that day."

The enemy aircraft came in from the setting sun which made observation difficult.

"My gunner was aiming at the approaching aircraft and let off a volley of lead. One of the rockets hit this man who died with his hand on the trigger."

The rockets hit one of the wagons full of ammunition and the explosions started.

"My brave JCO still managed to get to the gun, sit on top of the dead man and fired away at the attacking aircraft till they melted away into the darkness."

The dead gunner was given an in-situ cremation, but they had a larger problem at hand.

Fire had to be prevented from spreading to the other railway wagons and they went around searching for the engine driver who had gone into hiding once the air attack began.

"The driver found, we managed to uncouple the rest of the train from the burning wagon and moved it by about a kilometre from the siding preventing further damage. The engine driver was petrified at first, but we gave one man with a machine gun along with him to give him some reassurance."

This was the second casualty of the war and the ashes were taken back to the boy's village in Maharashtra after the funeral.

The railways were quick to acknowledge the bravery of the engine driver and he was awarded the equivalent of a Vir Chakra and a plot of land by the railways.

Then Major Gharpurey also had a hand in improvising the early warning system by getting direct access to the communication system of the railways.

"As you are aware, the Indian Railways, even at that time, had a large communication network spread all over India in a zonal manner. It was tappable. Without early warning, the effectiveness of our Air Defence dropped by 70% at least."

"I was initially based at a small railway station. I observed that the station master could speak to all stations in Rajasthan without hinderance just by saying 'Hello Jodhpur', 'Hello Barmer'. I had a discussion with him and requested him to give my Command Post a connection on this line. He readily agreed."

"I then spoke to the Munabao, Jodhpur and Barmer station masters and requested them to inform Gadra Road if any aircraft flew over them towards this side. I carried this line and their telephones (Funny looking gadgets they were!) and tapped their line at Khokhrapar once the railway line got connected. It turned out to be a limited but effective means of Early Warning," says the brigadier.

"We also did an improvisation of sorts by having our guns mounted on the wagons of the trains that were getting us food and water later. It was much like the second world war movies like Von Ryan's Express," remembers the veteran.

"Flat top wagons were attached at both ends of trains and we mounted one gun each on them to provide protection in their journey into Pakistani territory."

There was really no time to think as the war progressed. And before they knew it, it was over!

Major Gharpurey's unit continued to stay inside Pakistani territory and went on with their training till such time their withdrawal was ordered.

Gharpurey Sir shared another incident of the war with me. With the two casualties taking place and the bombs falling around, there was a young soldier who became delirious and wanted to go back home.

He wailed and sobbed through the night and this was detrimental to the morale of the troops.

"In war, one can give the harshest of punishments for soldiers who run away from soldiering. But I decided on a novel way to sort the man out and made an example of him."

A pit was dug in the desert and the man buried under sand with his head sticking out till such time he calmed down.

This trick worked well and soon the boy was back to his duty. "Fear psychosis spreads like fire!" declares the veteran.

The Narrow Escape

With the advancing Infantry Brigade reaching slightly ahead of Khokhropar in Pakistan, the engineer regiment had a tough task at hand.

The logistics had to reach the troops in the front and Lieutenant General G G Bewoor had plans of inducting an additional Infantry Division to go deep into Sindh by severing the Lahore-Karachi link.

However, by the time additional forces could be brought to bear in the area, East Pakistan had capitulated and the war was almost coming to an end.

"The occupied territory up to Khokhropar had to be held by our troops till such time withdrawal was ordered."

Gharpure sir had to travel up and down this axis quite frequently to take stock of the situation.

"I always preferred to drive with the driver sitting where I was supposed to since the terrain was tricky. My senior JCO followed me in another vehicle. Once while we were driving to a feature called Parbat Ali when we came under an aerial attack."

"One rocket went clean through the chest of my driver Shinde and through the rear floor of the open jeep. Thankfully, it did not explode and I was saved."

"My jeep was still roadworthy and I asked the JCO in the following jeep to carry out the last rites of the boy back at the unit HQ and join me later."

Breaking news of a soldier's death is indeed one of the painful things of war. Shinde's ashed were sent in an urn to his family and was accompanied by one of the senior JCOs of the unit.

"I was fond of Shinde and he had been with me for a while. He had just become a father a few days ago."

- Part 2: 'Gentlemen, we are at war!'

Air Commodore Nitin Sathe retired from the Indian Air Force in February 2020 after a distinguished 35 year career.

The author of three books, you can read Air Commodore Sathe's earlier contributions here.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com