'I would like to believe that out of this struggle (to effect climate change) will be born a generation that will be able to look upon the world with clearer eyes than those that preceded it;

that they will be able to transcend the isolation in which humanity was entrapped in the time of its derangement;

that they will rediscover their kinship with other beings,

and that this vision, at once new and ancient, will find expression in a transformed and renewed art and literature.'

Deeti. Antar. Piyali. King Thibaw. Neel. Kanai. Saya John. Fokir. Jodu. Tridib.

This mixed bag of intriguing names belonged to various characters in Amitav Ghosh's earlier novels.

Let's cut to the cast of characters in his latest book:

Cyclone. Tornado. Hurricane Sandy. Floods...

The Great Derangement flaunts even more interesting personalities. What's more, we know them very well.

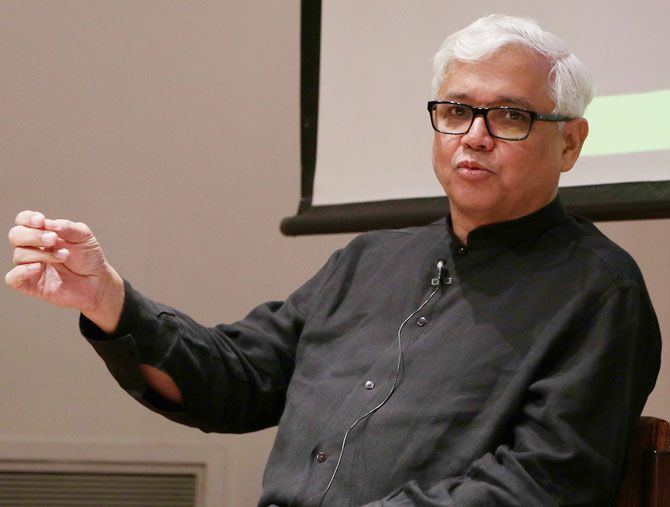

In the first part of an interview to Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel, Ghosh talks about how, in spite of knowing about the grave hazards of climate change, we blissfully ignore the odds. Or that we may not even survive to see the next few decades.

In the concluding part of this interview, the writer talks about India's ancient solutions to these problems. And how this is a story without a happy ending.

The solutions to climate change could lie in our age-old Indian wisdom. In returning to the earlier ways by which we lived. Amitav Ghosh concurs. "There were many ancient Indian traditions which were very well adapted to the landscape we live in. India, let's face it, is a land, which in a general sense is not an easy environment. In large parts, water is very scarce, especially in central India and some parts of the south."

"Going way back in history, rulers placed a great deal of emphasis on providing water -- creating water tanks, canals and natural reservoirs. This is true not just of India but all of Asia," he says. "The whole state structure was geared towards providing water, safeguarding water for times of scarcity..."

"That is exactly what we have turned away from. If you think that the first duty of the state in ancient India was to provide water, when you look at the state now... What is very striking about this recent drought is that the political class seemed to be quite uninterested," he adds.

Taking selfies (as Pankaja Munde, Maharashtra's then minister of rural development, did)?! "Yes, it was really shocking. The degree to which they were uninterested in the drought that the country is going through!"

Ghosh asks: "Have you written about the drought?" I have not, but Rediff.com covered the drought in a special series anchored by Prasanna D Zore and Uttam Ghosh.

He explains why he is asking. "It is not a story that is fun to do. Or fun to read. Unfortunately our audiences, that's what they want (fun stories). They often want stories that are either entertaining or... it is difficult to write a story of that kind about a drought! P Sainath (the Magsaysay Award-winning journalist) has been talking about this forever. He's been one of the pioneers."

"I was in Delhi. I asked a lot of the journalists there if they had written anything about the (recent) heat wave... And very few of them have. Because it is hard. What sort of story do you tell about a heat wave?"

What else did he want to stress about climate change, that maybe he did not get space or time to write about in his book? "I think one of the reasons why it's so hard to write about climate change -- and that's something I certainly didn't talk about in the book though maybe I will at some point in the future -- is that we all want to hear a story with a happy ending. A story with a good moral. A story that makes us feel, if not happy, certainly feel edified. But this may not be a story with a happy ending. May not be a story that will make you feel particularly edified."

And we may not even be here to be able to feel those emotions...

Laughs, bleakly. "Yes we may not be here. Exactly."

Ghosh, while highlighting how we once we lived in peaceable consonance with our environment, rather than out of tune with it, talks about how for centuries rural India was quite comfortable with living in conditions of scarcity. And they adapted to it. Be it in the kind of crops they grew, example the water-frugal millets. Lack of incentives to adhere to old farming customs, State policy and today's market forces encourage the growth of water-intensive crops for instance cotton and sugarcane.

Further, he feels many Indians have lost a taste for millets, preferring refined wheat or white rice, also water-intensive crops. And India is in danger of losing its farming traditions and its seeds, as it hankers after GMO seeds.

"Within our traditions there were many minor traditions which were well adapted to the environment... We are (now) producing mono cultures, when, in fact, there are even salt-tolerant varieties of rice (grown). All of these things are slowly getting lost. That is the most worrying thing. Slipping away exactly at the time when we most need them."

The most electrifying passages of Derangement is where Ghosh boldly paints out for us how the self-important 'mansion of the modern novel' was blissfully and stubbornly oblivious to the weather revolution beating away at its grand doors.

He underlines that the failings of the contemporary novel, not coincidentally, mirror what is wrong with the world and why our warped world has failed to give climate its proper due. The author gently berates his colleagues, past and present, for showing the weather no consideration.

Even more mind-bending for the reader is Derangement's blaming the 'mansion' of serious fiction too for climate change. The assignation of guilt here is tenuous. Some would find it far fetched. But it is about how modern novels, mostly Western ones, have encouraged us to think of our life as individual journeys. As simply solitary narratives. Voyages we steer ourselves.

As the novel evolved, at least in the Western world, it became a story, more and more, of one person's travails on earth. It moved away from stories about multiple interconnected lives, like Tolstoy's War and Peace. Novels had as much a role -- as other factors: Money and capitalism -- in brainwashing us to believe that our lives are about ourselves alone.

Contemporary fiction was responsible too for pushing us to become more and more selfish -- egotistical to the point where we don't care really about our carbon emissions, ie how much we generate and how it affects the collective good of the world.

Tracing the 'evolution' of the novel and the modifications Western pundits made to its structure, Ghosh chooses, as illustration, to quote a review by John Updike where he pulls up another writer for choosing to write a collective narrative: 'It is unfortunate, given the epic potential of his topic, that Mr Munif appears to be insufficiently Westernised to produce a narrative that feels much like what we call a novel... no central figure develops enough reality to attract our sympathetic interest.'

'There is almost none of that sense of individual moral adventure -- of the evolving individual in varied and roughly equal battle with a world of circumstance -- which since Don Quixote and Robinson Crusoe, has distinguished the novel from the fable and the chronicle... (it) is concerned, instead, with men in the aggregate.'

Ghosh triumphantly dissects -- you can hear the resounding crash of cymbals -- these somewhat arrogant and instructive pronouncements, that do not necessarily villainise the very tall Updike but the literary 'reformation' age he represented.

Why does Ghosh take on The Establishment he represents? "Well, because I am a novelist, you know. If I was an energy expert I would be thinking about the failings of the energy community. Because I am a novelist... climate change affects everybody, every aspect of our lives. It is not a domain for only experts of a certain kind. So I am trying to think of it in relation to my life, my practices, my profession, you know the things that I do. So I am thinking of it in relation to the contemporary novel... I feel fortunate that many writers and novelists have responded very positively to it. I am sure there will be lots of negative responses. I am sure many writers will look upon it in a different way."

But maybe it will take a Mahabharata or some other epic rejected by contemporary literature to reach the message of climate catastrophe to the masses. Ghosh in Derangement suggests that religions -- that control more opinions and with a better grip than nation States could possibly be instrumental in amplifying the message.

Given the author's belief in the magic of epics, isn't it time for a new tribe of epic writers to be born? Time for fresh kinds of writing. More Ramayanas, Iliads, Beowulfs Odysseys, Aeneids. Would he attempt it?

Laughs. "I can't see myself (doing that). The thing about the epic form is epics are written in verse. I don't write verse. But yes, it certainly it is something that has crossed my mind. It is something we all have to be thinking about. New ways of writing. How do we write about what the world is currently undergoing?"

Trepidation on how India will soldier its way into an uncertain future complicated by the scourge of global warming made writing The Great Derangement imperative, he says earlier.

India has a central role in his life. She firmly owns his soul. The gentleman, in thick black glasses and a black kurta before you, might have lived all over the world, but his sentiments seem to have mulishly resisted travelling even across Howrah Bridge.

Over time, he believes, he has become closer to India. He spends even more time here, though his life has always been divided between New York and India.

Has the increasing durations in India, coupled with the passage of time, influenced the views he has reached in Derangement? Especially in connection with the anger he feels for colonialism?

Isn't it that in our youth the glossiness of the West seems attractive but when understanding grows, with age, you recognise the West got where it did -- its shine -- at a cost? Is it this stage in his life that has brought this book?

He answers haltingly. Thoughtfully, "You are right. I think. (Sighs) It is not really a question of the shortcomings of the West or anything. It is just that... for me, I am Indian. I feel Indian... I have a certain level of comfort in India. With my friends. My relationships. Yes it is true, just as you are saying, we all feel disconnectedness."

I ask him: Has your thinking matured in a certain way making this book possible?

"Yes, absolutely."

Talking about modern culture, in general, he adds: "The whole culture now encourages us to think about ourselves. It is the selfie culture."

"Modernism, modernity thinks of itself as something very particular to the West."

That is a stirring line in Derangement: "The one feature of Western modernity that is truly distinctive: Its enormous intellectual commitment to the promotion of its supposed singularity..."

He counters that later with a statement of hope: "But I would like to believe that out of this struggle (to effect climate change) will be born a generation that will be able to look upon the world with clearer eyes than those that preceded it; that they will be able to transcend the isolation in which humanity was entrapped in the time of its derangement; that they will rediscover their kinship with other beings, and that this vision, at once new and ancient, will find expression in a transformed and renewed art and literature."

- You can buy Amitav Ghosh's books here.