'Like a majority of youngsters in the valley, they were left with just two options in life: Pick up a stone or take up a gun.'

'That journey through the heartland of Kashmir's new insurgency movement was to help them decide what to do with their lives.'

'And I was to bear witness.'

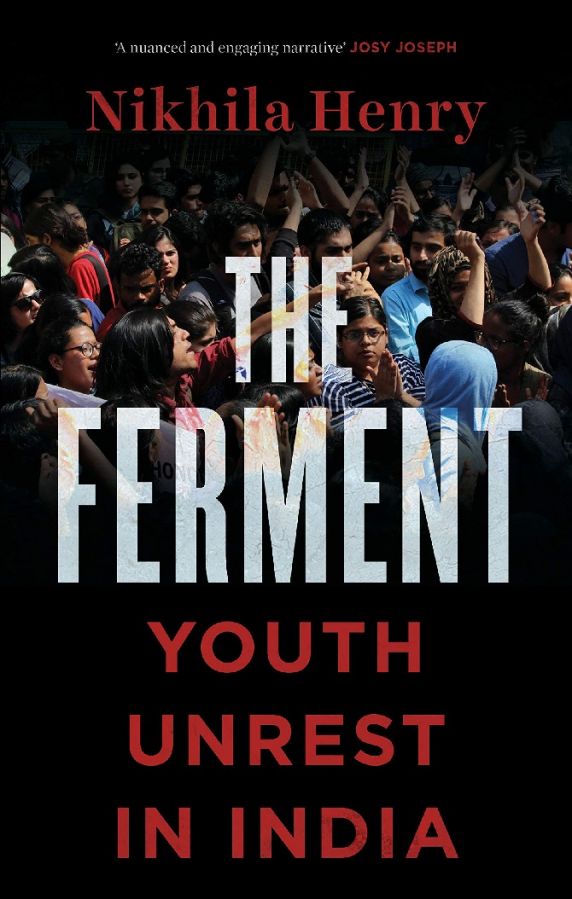

A revealing excerpt from Nikhila Henry's The Ferment: Youth Unrest In India.

Born in 1992, at a time when Kashmir's foreign militancy was at its peak, Qa was an average Kashmiri youth with a bleak past and an uncertain future. His father had been killed by insurgents when he was a boy and his mother suffered from insomnia.

His friends, Sa and Ya, shared similar histories. Their fathers killed and their families throttled by the tensions in their homeland, the two youth, like Qa, had lived a difficult life.

In September 2016, two months after the killing of Burhan Wani, the 22-year-old Commander of the Hizbul Mujahideen, the three youngsters started on a trip that spanned four districts of South Kashmir -- Anantnag, Khulgam, Shopian, and Pulwama -- to take stock of the first massive uprising they got to witness in their lifetime.

I accompanied them, uncertain of the possibilities that were to unravel during the trip. The odds that stared at them throughout the journey were to take me to the heart of Kashmir's conflict and the angst of its youth.

When I first met Qa at his two-storied posh residence in Anantnag, he was reading Noam Chomsky's Culture of Dissent. The rolled-up sleeves of his denim shirt revealed a tattoo on his forearm that read Ya Imam Akhir Zamaan ('O Messiah of the troubled times').

Kashmir was indeed in need of a messiah that summer; 70 per cent of its population aged below 31 were up in arms against the Indian State. Every nook and corner of the land brought forth stories of youngsters with crushed bodies and an unfaltering spirit.

Even after 7,000 people were arrested and 450 charged under the Public Safety Act -- called a 'lawless law' -- and more than 3,000 injured and 94 dead in just over three months, the youth of Kashmir, like the three men in that Maruti 800, were fighting it out on the street, torching buildings and pelting stones. They wanted freedom from the immediacy of a troubled, alienated life.

As the car started out from Lal Chowk of Anantnag, Qa told me why I should never name him or his friends. First arrested at the age of 16 for participating in protests for Kashmir's freedom, he had gone on to become one of the leaders of the 2016 uprising.

The three men were radical and they were travelling to meet a friend, S, who was on the radar of Indian security agencies. Most importantly, they, like a majority of youngsters in the valley, were left with just two options in life: pick up a stone or take up a gun. Under such uncertainty, it was indeed risky to reveal names.

That journey through the heartland of Kashmir's new insurgency movement was to help them decide what to do with their lives. And I was to bear witness.

Nothing seemed out of place in that conflict-torn land; the army trucks, the Central Reserve Police Force camps, the jeeps of the Jammu and Kashmir police parked everywhere, the crooked roads barricaded on and off with stones and branches of trees and, most importantly, the young men and boys with scrutinising eyes standing guard, checking every vehicle that went by.

Normalcy is a cultivated taste and habit rules the mind.

Ya steered the car to the left to reach the heart of Khulgam. At a distance, he could see a group of boys in their early teens standing guard near a pile of shapeless white rocks scattered with some effort on the narrow road. They were the first rung of young troopers of Kashmir.

'Where are you going?' a child asked, mistrust in his eyes, as the car came to a halt. His friends stood a few feet away.

'To Shopian,' Sa answered, irritation ringing in his voice; that was the third time we were stopped by stick-holding children.

'Why?'

'We have friends to meet there. My so-and-so lives there...' Sa in the front seat and Ya behind the wheel rambled on completing each other's sentences. The youth in the car, by habit, measured words by the second without offending or raising suspicion. And the would-be youth on the road weighed the tension and gauged the situation.

The valley had turned into a well-guarded fortress where entry and exists were checked by two kinds of people: One, the army and paramilitary men, who often threatened the locals with fatal consequences; and the other, local young men and boys ready to guard their people and land till their last breath.

The vehicle was allowed to move after a thorough check and the tallest boy waved it by as Qa bellowed, 'Shukriya, izzat izzat. (Thank you. Respect).'

Twirling their lathis, the boy brigade resumed their respective positions in the middle of the road. They had a territory to guard and their eyes, aging under the weight of uncertainty that had gripped their watan, remained focused on the car's number plate seeking clues to identify mukhbir, or traitors of their land who collaborated as informants to the police and security forces.

A generation had awakened after July 8, 2016, the day that saw Burhan Wani gunned down by Indian security forces. Burhan was from Tral, Pulwama, in south Kashmir and his legacy still haunted the four districts of the South.

During the journey, Ya revealed what it was to be young and living in Kashmir. Each youth in India's Paradise was bogged down by the history of the land and memories of the past.

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, during which three-fourths of the valley's population was in their formative years, four uprisings -- including the one in 2016 -- had shaken Kashmir.

In 2008, close to 70 were killed by Indian security forces and, in 2009, after the alleged rape and murder of Niloufer and Asiya Jaan, 43 were dead.

In 2010, the figures were higher: 120 dead and many more injured. 2016 was the fourth and the biggest both in the scale of death and participation.

2016 was the fourth and the biggest both in the scale of death and participation.

With the land intermittently on the boil, it was difficult to live normal lives. Childhood meant trouble, disrupted school days, and criminal cases; and youth was agony, joblessness, more trouble, and criminal indictment.

With unrest spurred on by the army presence, and insurgency engulfing their lives, the academic calendar was mostly never adhered to. Hitting a 210 working days target in schools was impossible. And the institutions of higher learning remained shut during a large part of the year whenever uprisings gripped the valley. Jobs were scarce.

In 2010, a meagre 10 lakh of the population were employed in the service sector which had by then boomed in the rest of the country. As per the Planning Commission, 80 per cent of the population depended on agriculture in 2003.

The share of agriculture in total employment generation was 61.6 per cent in 2010, and all was a gamble.

There was no way out for youngsters, and always an agitation brewed inside living rooms, school recess periods, and college vacations.

'Was it not obvious that we were just waiting for the opportune moment?' Ya, who worked as a sales manager, said with a smile lifting the corner of his mouth. It was not obvious that Kashmir's youth had been gearing up for five years since 2010, the year of the last major unrest. All seemed silent.

The Government of India had found militancy receding as the armed brigade indulged in fewer strikes. The youth had gone back to studies and career goals, security experts had pointed out to inquisitive journalists.

But the wounds of Kashmir were always sore. It took only the birth of a martyr for the volcano to erupt.

As we drove down the road that connected Khulgam and Shopian, we noticed bricks and stones from the previous night's faceoff with Indian security personnel strewn around and walls that read SHAHID BURHAN.

Burhan Wani continued to remain the elixir that fed an agitation, even two months after his death. Through street graffiti, photographs, and paintings plastered on the outer walls of houses and grocery stores, the young of the South kept Burhan alive.

The agitation this time touched each home and each curfew school. The youth were no longer scared of revealing their love for the slain commander....

...They welcomed him into their lives and called him bhai (brother). They sang odes to him.

For them Burhan was a reflection of their inner self; a teenager who during his school education dropped out to wield a gun because he could not bear the travails of daily life.

In Kashmir, there was no dearth of such disillusioned youth. Most homes had stories of past atrocities to tell and hence, each living room could churn out at least one stone-pelting youngster.

Sa warned me as the car took a detour towards Shopian, 'We will be stopped again.'

From a house that stood in the middle of a field, rose heart-wrenching wails. A boy had died, hit by a tear gas shell. His body was being taken for burial in a procession of men, women, and children clad in white.

It was just another death and yet another funeral. But the tears were as fresh and the prayers as loud as the first, when it all began. Among those killed, over 80 per cent were between 12 and 26 years of age.

The car hesitantly passed by as we remained silent inside.... Shopian was just a few more kilometres away. As I sat numbed by the cries from outside, Qa's singing soothed us. Woh mere do jahan sath le gaye, tamam dastan sath le gaye... his voice reached a high note. In Qa's songs, sung from a deep-seated loss, most found refuge....

Turka Wangam was the destined place for the crucial meeting. Sa raised his hand as S walked out of a mosque. He was an all-black-clad bearded man in his mid-thirties. 'They cannot touch the children here,' he spoke of the army.

The youth had kept the men in uniform at bay and there was no army presence in the locality. If needed, Kashmir's young could take over self-governance.

The three youth took me to a pink house with green doors that was surrounded by apple orchards and walnut trees. Most of Kashmir's self-employed youth worked in such orchards and grain fields. The percentage of self-employed households in the state was as high as 68 per cent...

...Sa, who was a graduate with a sharp sense of humour, was not ready for prayers. 'I stopped praying a long time ago; life is too tough. But here I might have to go for namaz,' he said.

Kashmir's young were: a mixed bag unlike what they were made out to be in popular perception -- war-mongering, uneducated lowlifes. Like the three men who owned the Maruti 800, the many young people in Kashmir included the well-educated and the well-read in politics and economics.

There were, of course, the illiterates and semi=literates, as Kashmir's literacy rate was many notches below the Indian average of 74.04 per cent. But there were also others: People well-versed in scriptures, who were either believers or non-believers; the businessmen, doctors, and teachers who could gather a crowd for protests within minutes; and the students of schools and colleges who could call a strike anytime to satisfy their principles.

The two men with Kalashnikovs who walked into that house in Shopian in the middle of the day were proof of this rich cross-section of youth in the valley; young and educated, they still had guns strapped to their shoulders. S readily arranged a meeting.

The two walked in wearing dark grey and brown pherans, and seemed pleasant and familiar with everyone present. Sitting in the middle of the carpeted living room, the two men uttered a prayer before breaking bread.

Sa gestured at me to pay attention. The men were no strangers in the locality; but they were Hizbul Mujahideen warriors out on business. The younger-looking man of the two, perhaps 23 or 24, smiled. He was at ease in the house and spoke fluent English.

During the five years that Burhan Wani was at the helm of the outfit, the Hizbul had become a household name. And its young soldiers had come to be treated like the boys next door. Not much had changed after Burhan's death, only that the Hizbul's advances into lives outside the forest cover had become rather open after July 8.

I asked the young man who was wearing the grey pheran, 'What is your future like? Do you think you will ever return home?' The number of insurgents who surrendered or collaborated with the police and Indian security forces had reduced starting 2010. The outfit had also seen a rise in new recruits under Burhan's Commandership.

'I will if, Insha Allah, God permits Kashmir becomes free. I do miss my mouji (mother),' he said, as his boyishness shone through the shroud of secrecy. A three-year-old boy of the house had by then climbed into his lap.

Qa motioned the two men into another room. They had a discussion behind closed doors. When Qa came out, he was smiling. Some plans were not meant to be shared with outsiders. It was time for us to leave.

The trip, surreal as it was, revealed a picture of Kashmir which usually escaped the eyes of India's heartland. It became clear that the mass uprising which lasted over 130 days, spreading itself across summer and winter in time, and north, centre, and south spatially, was the product of at least two-decade-old travails, the new generation of youth in valley had faced during their short life time.

And Burhan Wani was the symbol of this generation.

Painted in green on the compound walls of Burhan Wani's home in Pulwama were the words 'Burhan zinda hei'; and it was true. By virtue of their shared experiences, Burhan and the young people who pelted stones and faced guns in his name had struck a chord long before his death.

On our way back to Anantnag, Qa asked me what I thought of my interviews with him the previous night. On the Khanabal Pahalgam road in Anantnag which was under total army control, we had met for a brief while. I remembered the nauseating smell of putrefied milk emanating from a refrigerator in the shopping complex where we had the meeting. Kashmir had, by then, faced over 60 days of complete shutdown and all was rotten in closed grocery stores.

'Do you think we are fighting for the wrong reason? That we are lost souls? We don't have a life beyond all this; that is the truth,' he said as he reminded me that he had returned to Anantnag after completing his undergraduate studies in a college in a city in southern India.

For those Kashmiri youth living outside the state, life was at least a bleak possibility. But for those who come back to the valley, not much was left but the surety of chaos.

Excerpted from The Ferment: Youth Unrest In India by Nikhila Henry with the kind permission of the publishers, Pan Macmillan Publishing India Private Limited.