To achieve herd immunity, rapid vaccination is the only hope.

Abhishek Waghmare reports.

More than a year into the coronavirus pandemic, India's reasons to celebrate are waning and worries are rising by the day.

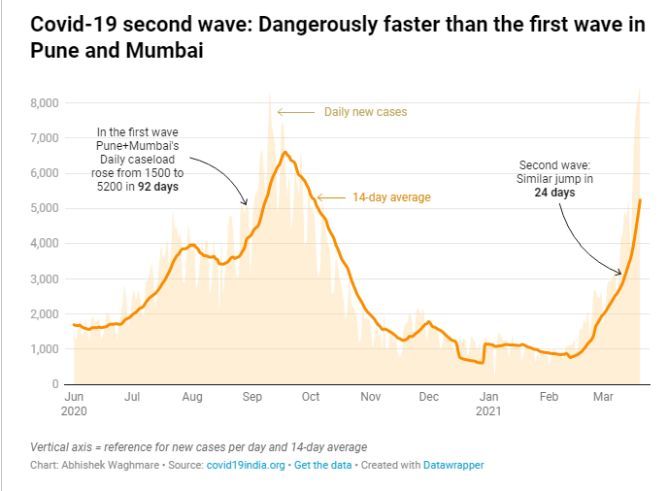

In the two hardest-hit districts, Pune and Mumbai, the second wave is significantly more potent than the first, shows chart 1 (below).

The 14-day average of new daily cases has risen from the low of about 1,500 to over 5,000 in less than a month, about four times fast than the time taken for this jump in the first wave.

This may even worsen from here on.

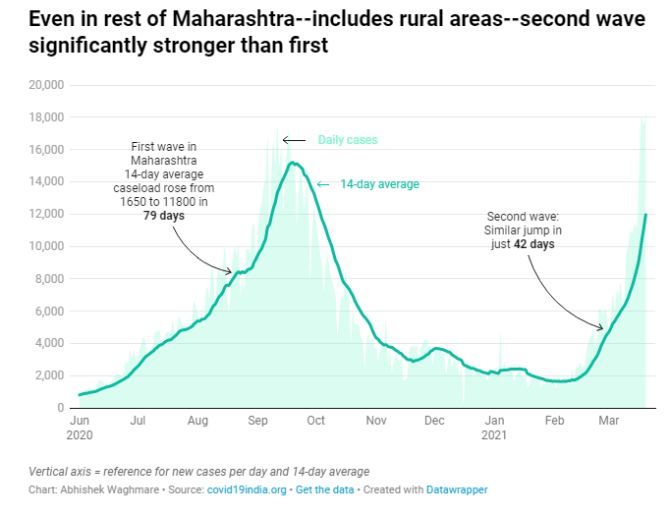

Now these two cities were the reason for Maharashtra being the most affected in the first wave.

In the second wave, even the rest of Maharashtra is on a worse trajectory, with the speed three times faster than the first wave, reveals chart 2.

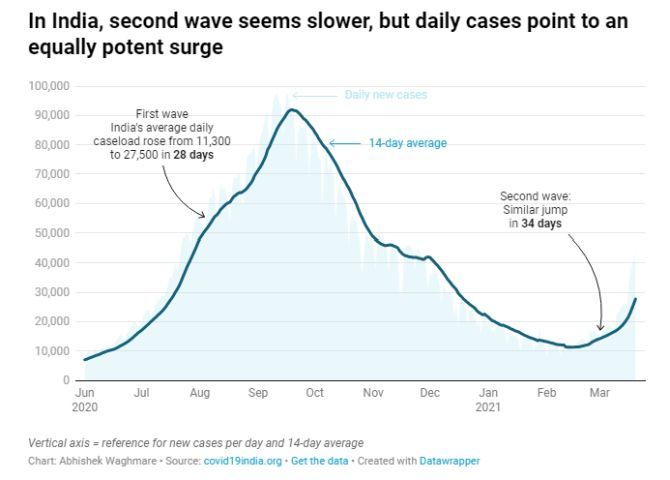

The worsening spread in Maharashtra makes the second wave in the country as a whole look milder.

It took five weeks to take the 14-day average of new national cases to 28,000 this time, compared to four weeks in the first wave, shows chart 3 (below).

But daily cases are rising fast, and pointing to a worse outcome.

Now, seroprevalence studies have shown that only one in five Indians were infected, and four in five still remained susceptible to infection as we entered 2021.

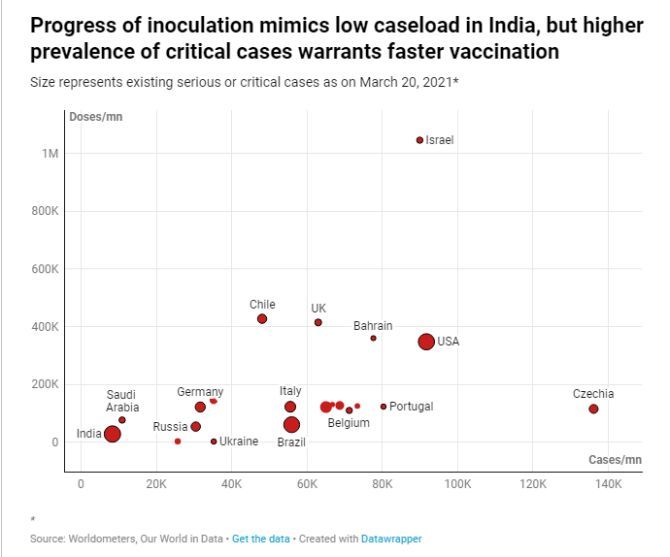

To achieve herd immunity, rapid vaccination is the only hope.

Chart 4 (below) illustrates that India is still way behind other countries in vaccination (doses administered per million).

Though the caseload per million people is low in India compared to other countries, testing prevalence is also low.

A worrisome fact is that India has the highest number of critical COVID-19 cases in the world.

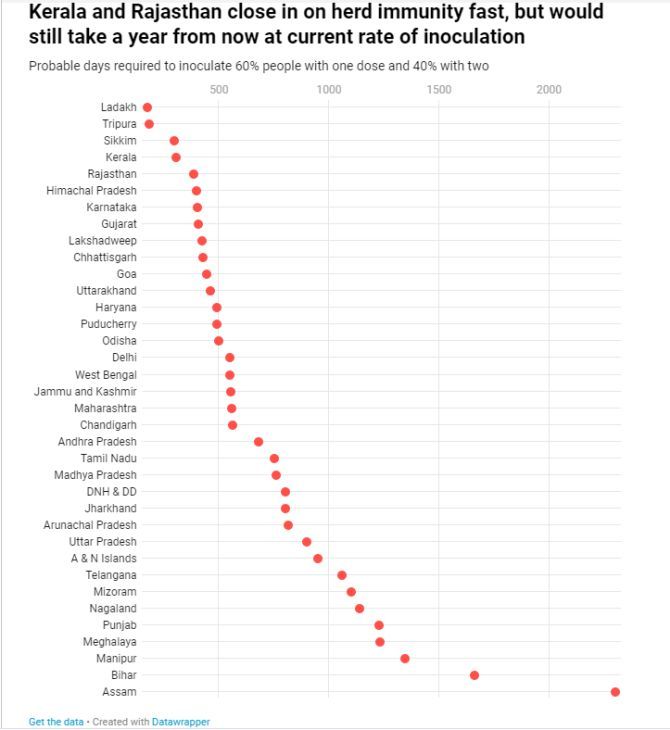

On this note, chart 5 (below) shows which states would get close to herd immunity fast, and which ones would take years if they continue with the current weekly rate of inoculation.

While Kerala and Rajasthan may make it the fastest, states such as Bihar and Assam may take as long as 2024 to vaccinate half the population at the current weekly rate.

Maharashtra may not be able to vaccinate half of its population by middle of 2022 at its current rate.

The analysis assumes that 50% of the population is inoculated if the number of doses administered is equal to the population.

© 2025 Rediff.com -

© 2025 Rediff.com -