Modi is seen as exceptional not only on account of his acts but also owing to his style.

He appears to sacrifice his life for the people -- like a fakir, a figure he came to epitomise even more in 2020 by growing a long white beard.

Charisma is above accountability, and Modi has grasped these dynamics.

An exclusive and fascinating excerpt from Christophe Jaffrelot's Modi's India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy.

The words that Modi's supporters (known as bhakts [devotees]) use to describe his power often belong, indeed, to the realm of supernatural forces.

Certainly, this image has been constructed by the public relations agencies he has hired since his Gujarat years, but a large fraction of the Indian public has made it its own in a rather uncritical manner.

Hence the notion of "vishvas politics" articulated by Neelanjan Sircar, which assumes that Narendra Modi not only is above accountability but that he cannot do anything wrong.

This was particularly obvious during the COVID-19 pandemic, a crisis that was not handled well by the government but that Narendra Modi was not blamed for.

When public opinion is so inclined, one of the limits to power vanishes if any form of authority -- including abusive ones -- seems legitimate.

Narendra Modi has acquired charisma in the Weberian sense owing to the manner in which he has achieved "big things" -- which were not necessarily perceived as good things, as evident from the way the 2002 pogrom was reported in the media.

He has shown his strength through disruptive decisions affecting the life of all citizens, such as demonetisation.

He has demonstrated his taste for the spectacular, with the statue of Sardar Patel, the tallest in the world.

He convinced the UN to recognize June 21 as International Yoga Day.

He has dared to attack Pakistan militarily beyond the territory of disputed Kashmir in Balakot.

And he has initiated policies no one has ever attempted, such as the abolition of article 370.

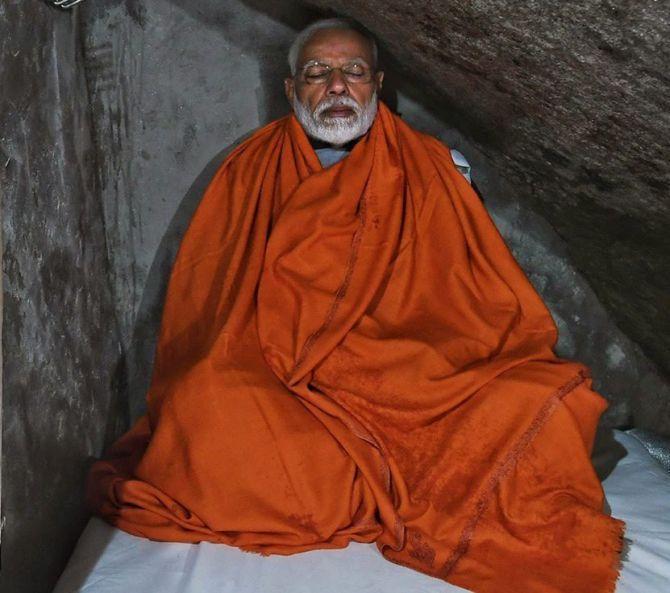

But Modi is seen as exceptional not only on account of his acts but also owing to his style.

He appears to sacrifice his life for the people -- like a fakir (a word he uses to refer to himself), a figure he came to epitomize even more in 2020 by growing a long white beard.

This echoes the ideal of the selfless world renouncer, a highly prestigious figure in Indian culture -- and which Mahatma Gandhi (the most remarkable Indian "brand" for Modi) exemplified.

Ambedkar in fact had Gandhi in mind in his criticism of the personality cult that is so prevalent in India in the above citation, because he was aware, as the Rudolphs were to show, that while Gandhi's charisma had "traditional roots," it was power oriented: the Mahatma was keen to exercise dominant authority.

If Modi belongs to a school of thought that has always opposed the Mahatma, he has emulated his "saintly politics" to persuade Indian voters that he devotes all his energy to the nation, and even to the poor, in actions devoid of all corruption.

Last but not least, Modi, due to his social background, appears as a man of the people who has suffered from class and caste hierarchies and who cultivates a sense of victimization that Indian plebeians cannot help but share.

He also cultivates his proximity to the people through his monthly radio program, Mann Ki Baat.

To sum up, Modi is a pure populist a la Ostiguy because he combines these exceptional achievements and a sense of morality with a very humble background, which means that he is seen as "a man like us who managed to become a superman."

This is the main reason why he is not punished by voters when he fails to deliver on the economic front.

Even in terms of policy, people retain their trust in him -- hence the "vishvas" feeling.

But Modi is more than a populist, he is a national-populist.

His style is especially popular because he has restored people's pride and sense of dignity.

Thanks to him, not only do the poor feel better respected in India, but Indians feel they have earned the world's respect.

Modi has constantly traveled across the globe, and these trips have been systematically publicized in the media on purpose.

He has made a point of hugging the leaders of the world in front of the cameras and sharing the dais in large rallies with the most powerful, including Donald Trump in Houston and then in Ahmedabad.

This international recognition has had a particularly strong impact on a population suffering from a deep, historical sense of vulnerability: the syndrome of the effete and "dying" race affecting Hindus, since the British Raj has remained particularly strong among those who fear the Other, who are jobless, who feel useless and/or have undergone socioeconomic decline.

Gandhi, as the Rudolphs have shown, gave Indians renewed self-esteem by creating a "new courage" based on nonviolence.

Modi has given them self-respect, a word he repeated many times on August 15, 2019, during his Independence Day speech.

Citizens are more prepared to pay allegiance to a strong leader who is endowed with exceptional, superhuman qualities, who protects them and restores their self-esteem.

As he can do no wrong, the people willingly suspend their critical thinking and readily renounce some of their freedoms.

This process was exemplified by the way Indira Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi were reelected in 1980, less than two years after the Emergency -- as if they were not responsible for this phase of dictatorship.

Why were they not punished not once but again two years later? The interviews that Emma Tarlo conducted in Delhi slums that had resulted from the government's "rehabilitation" policy showed that "none [among the interviewees] associated their sufferings with Indira Gandhi," who was still seen as "a great leader," a "world-famous leader" -- like Sanjay.

Charisma is above accountability, and Modi has grasped these dynamics.

The last reason why few people resist the regime's liberticidal inclination is fear, a sentiment that is paralyzing an increasingly large number of Indian citizens.

This factor has been mentioned previously in relation to newsrooms, but the media are not the only targets, and other people than journalists have censored themselves because of fear.

In 2018, a division bench of the Bombay high court observed: "We are witnessing a tragic phase in the country today. Citizens already feel that they can't voice their concerns or opinions fearlessly."

Besides those who are afraid to leave their neighborhood because their physical appearance designates them as a minority member, any institution and any group may be targeted, including bureaucrats and judges -- who may be transferred or even sued and jailed.

Even some businessmen live in fear of Income Tax Department, Enforcement Directorate, and CBI raids, as suggested in previous chapters.

The scion of one of the most prestigious industrial families of India, Rahul Bajaj, told Amit Shah during an industry awards event in Mumbai: "Nobody from our industrialist friends will speak, I will say openly..... An environment will have to be created..... When UPA II was in power, we could criticise anyone.... You [the government] are doing good work, but despite that we don't have the confidence that you will appreciate if we criticise you openly."

He added, in relation to the wave of lynchings: "It creates an environment of intolerance and we are scared. We don't want to say certain things but we see that until now no one has been convicted."

Amit Shah responded, "There is no need for anybody to fear."

But the psychosis Bajaj was referring to has been exacerbated by certain State policies as well as official speeches.

India has acquired some attributes of a police state not only by resorting routinely to draconian anti-terror laws like the UAPA and by charging journalists for sedition, as mentioned above, but also by developing a sophisticated surveillance system.

The accused in the Bhima Koregaon case were booked on the basis of evidence retrieved from their phones and computers.

Soon after, it appeared that these phones and computers had been infected by snooping software developed by an Israeli company -- the NSO Group -- which sells it only to government agencies.

This software, called Pegasus, gives attackers control over the mobile device of the person targeted.

WhatsApp -- the application used by the attackers to break into phones -- has sued the NSO Group, but the Indian government, which in the previous months and years had upgraded its collaboration with Israel in several technological domains, including artificial intelligence, has not commented on this affair.

In parallel, the Government of India has initiated a surveillance system by resorting increasingly to facial recognition.

After the Delhi riots, Amit Shah declared, "Police have identified 1,100 people through the facial recognition technology. Nearly 300 people came from Uttar Pradesh. It was a planned conspiracy."

How could the police know?

It seems that "the footage procured from CCTV, media persons and the public was matched with photographs stored in the database of Election Commission and e-Vahan, a pan-India database of vehicle registration maintained by Ministry of Road Transport and Highways."

Gautam Bhatia points out that "such 'dragnet' screening is a blatant violation of privacy rights, as it essentially treats every individual like a potential suspect, subject to an endless continuing investigation."

This technique is more and more systematically resorted to by the government, as the Indian parliament has yet to enact a personal-data-protection law loose enough to allow the government to use Aadhaar for facial recognition as well.

The Supreme Court forced the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting to withdraw its proposal for social media monitoring in 2018, considering that if such a proposal were implemented, India would be "moving towards a surveillance state."

But in 2021, the government is still eager to develop a tool that would monitor social media users to identify their "sentiments" and track trends relevant to "government related activities" that "may have adverse negative impact on socioeconomic fabric of society."

These words, which hark back to the authoritarian orthopraxy mentioned above, come from the expression of interest that the I&B ministry has floated to empanel an entity to create such a tool.

Even before such a tool has seen the light of the day, the authorities have already arrested a large number of social media users, including journalists, for messages or videos they had posted on Facebook or WhatsApp, even posts that were sometimes several years old.

In 2019, Suhas Palshikar concluded his contribution to Majoritarian State by considering that "electoral defeat alone can puncture the BJP's resolute march towards crafting a new hegemony," but electoral defeat may not make much of a difference, or, to be more precise, while it is a necessary condition, it may not be a sufficient one.

First, as mentioned in part II, the Sangh Parivar is so deeply entrenched in the social fabric that it may continue to dictate its terms to the state on the ground -- and to rule in the street.

Second, the "deep state" may remain in a position to influence policies and politics even if the BJP is voted out.

In that sense, Hindu nationalism does not rely as much on one man to push its agenda as the BJP does to win elections.

Excerpted from Modi's India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy by Christophe Jaffrelot Copyright 2021 by Christophe Jaffrelot. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com