'No matter how severe sanctions the UN security council imposes on North Korea, the impact of the sanctions would depend on how faithfully they are enforced by China,' says Dr Rajaram Panda.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un seen here with young North Koreans in this undated photograph released by the Korean Central News Agency to Reuters.

The North Korean issue continues to hog the international limelight.

North Korean leader Kim Jong-un's bellicose utterances are matched by similar rhetoric from United States President Donald J Trump.

We are familiar with words like 'annihilate', 'destroy', 'fire and fury' and similar language used by both leaders. It vitiates the situation instead of addressing the issues at hand.

No amount of pressure or sanctions imposed on North Korea to dissuade it from pursuing its nuclear and missile programme have yielded any tangible results.

Pyongyang has made it clear that its nuclear programme is not negotiable. Its ultimate goal is to be recognised as a nuclear State and to be treated at par with any other nuclear State.

That seems to be ultimate insurance for the survival of the Kim regime.

If this is the case, what does United Nations Resolution 2397 -- which passed new sanctions against North Korea on December 22, imposing some of the strongest measures yet restricting trade by and with that country -- mean to the issue of the denuclearisation of North Korea?

Trump is seemingly working his way towards a near total trade embargo as mentioned by US Ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley.

If Resolution 2379 succeeds in banning North Korea from buying machinery, electronics, vehicles and metals, its earnings from exports could dwindle to just a few million dollars per month or so it is believed.

But is that really the case?

The UN security council's additional round of sanctions, which were unanimously imposed, target sectors that fuel North Korea's illicit weapons programmes.

The new resolution builds on three rounds of tough sanctions imposed on Pyongyang earlier in 2017.

If fully implemented, it will cap North Korea's annual import of refined petroleum products, such as gasoline and diesel, at half a million barrels, down from 4.5 million in 2016. Exemptions would only be allowed on a case-by-case basis, with UN security council approval.

The sanctions also entail other punishment that include cutting off revenue from North Korean labourers sent abroad to work.

It is no secret that the regime confiscates the wages of these workers so that it can fund its illicit programmes. Under the new UN resolution, all North Korean workers must return home within two years.

It is estimated that between 50,000 to 80,000 North Koreans work in China and about 30,000 in Russia.

The US alleges that North Korea illegally exports coal and acquires prohibited oil through deceptive shipping practices. The new sanctions intend to prevent this by closing loopholes in the maritime interdiction and inspection regimes.

The new measures also prohibit North Korea from importing all industrial machinery and equipment and certain transport vehicles which accounted for one-third of its total imports in 2016.

More than a dozen North Korean individuals in the banking sector face travel curbs and asset freezes.

The latest provocation for imposing these additional sanctions was Pyongyang's launch, on November 28, of a newly developed intercontinental ballistic missile called Hwasong-15, which it claimed has the capability of delivering nuclear warheads anywhere in the continental United States.

That test was the third ICBM test and 20th ballistic missile launch -- all in 2017.

Though these missile tests frustrated China -- North Korea's long time and only patron -- Beijing could do little to prevent it.

Though Beijing does have leverage to rein in Pyongyang, it is debatable if it wants to do something about it.

At times, Beijing has demanded that Pyongyang abide by the demands of the international community and implement the UN security council resolutions, besides refraining from conducting any further nuclear and missile tests.

At other times, China has indulged in secret and illegal trade with North Korea in violation of UN security council resolutions.

It remains unclear if China is serious about going along with the international community to put real pressure on North Korea.

Though Beijing stresses the importance of dialogue and consultations to seek a peaceful settlement, it is doubtful if is really serious as it does not use its leverage over Pyongyang.

Russia's position is equally unclear. This stems from Russia's position that the draft text of the UN resolution did not include wider and lengthy discussions among all security council members.

Russia alleges that the US rushed through the resolution after entering a bilateral agreement with China.

The latest sanctions were the fourth imposed on North Korea by the security council in 2017 and the 10th since 2006, all aimed at stopping Pyongyang advancing its illicit weapons programme and bringing it to the negotiating table.

Since all previous sanctions have failed to prevent North Korea from pursuing its weapons programme, it remains unclear how the latest one can make any difference.

Though UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres welcomed the security council's adoption of the resolution, his observation that a political solution aimed at de-escalating the situation as the ultimate alternative has merit.

The security council had slapped three sets of sanctions on North Korea in 2017.

On August 5 its sanctions targeted North Korea's iron ore, coal and fishing industries. The September 11 sanctions aimed at textiles and limiting oil supply.

The December 22 sanctions focused on refined petroleum products.

It denies international port access to four North Korean ships suspected of carrying or having transported goods banned by international sanctions targeting Pyongyang.

The US seemed to have requested banning the four vessels -- the Ul Ji Bong 6, Rung Ra 2, Sam Jong 2 and the Rye Song Gang -- along with measures targeting ships registered in other countries.

While China agreed to target only the four North Korean ships as part of international efforts to curb Pyongyang's missile and nuclear programmes, the US insisted on including other ships flying the flags of Belize, China, Hong Kong, Palau and Panama.

The US noted that trafficking of banned goods allowed North Korea to stock up and transfer cargo between different ships on the high seas.

The August 5 resolution provided for blocking suspected vessels from ports, except in the case of humanitarian need as determined by the security council's sanctions committee.

On October 5, the UN identified four ships 'carrying prohibited goods', leading to a ban on port access, the first such case in UN history.

The four vessels were registered in the Comoros, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Cambodia and North Korea, and were targeted for the illegal transport of coal, iron and North Korean fish.

China shows no willingness to cooperate and implement sanctions to blacklist six ships for illegally shipping to North Korea and asked the UN not to do so.

South Korea says one of the six ships, the 11,253-ton tanker, the Lighthouse Winmore, a Hong Kong-flagged vessel, was suspected of transferring 600 tons of refined oil in October 2017 to North Korea in violation of UN sanctions and therefore seized it.

This corroborated Trump's accusation of China letting fuel oil flow into North Korea through illicit ship-to-ship transfers on international waters.

There was no immediate evidence of official Chinese involvement in the Lighthouse Winmore's dealings with the North Koreans. China insists there was no such violation.

The Lighthouse Winmore, leased by a Taiwanese company, docked at the South Korean port of Yeosu on October 11 to load 14,039 tons of refined petroleum from Japan.

Though it departed four days later heading for Taiwan, it changed route and transferred the refined oil to four other ships in international waters, including 600 tons transferred to the North Korean ship Sam Jong 2 on October 19.

A similar ship-to-ship transfer involving another North Korean ship, Rye Song Gang 1, was captured in satellite photographs released by the US treasury department on November 21.

On the closing day of 2017, South Korea revealed it had seized another ship, a Panama-flagged vessel, suspected of transferring oil products to North Korea.

The ship, KOTI, was seized at Pyeongtaek-Dangjin port on the west coast, south of Incheon. Owing to the sensitivity of the issue, further details were not revealed.

The UN security council resolution on December 22 empowered member countries to inspect and impound any vessel in their ports that was believed to have been used for prohibited activities with North Korea.

South Korea used this power and impounded the ship in question after questioning the crew members.

Under those sanctions, countries cannot export more than a half million barrels of refined petroleum products, an 89 per cent cut from previous annual shipments, and four million barrels of crude oil in total per year to North Korea.

All shipments ought to be reported to the security council so that it can be determined if the caps have been reached.

Ship-to-ship transfers of oil on the high seas are banned as such routes could be used as a loophole to avoid the sanctions.

Understandably, Trump is angry and expressed disappointment over China's complicity in oil transfers to North Korean ships in international waters and therefore sees no friendly solution to the North Korean problem.

No matter how severe sanctions the UN security council imposes on North Korea, the impact of the sanctions would largely depend on how faithfully they are enforced by China.

China handles 90 per cent of North Korea's external trade, including nearly all of its oil imports.

Though China denies its involvement in ship-to-ship oil transfers, given its other considerations, it is a claim difficult to believe.

Trump has urged Chinese President Xi Jinping to use China's economic leverage to stop North Korea's nuclear weapons programmes, but China is either unwilling or unable to exercise that leverage.

The truism is that Beijing will never rejoice with the prospect of a regime collapse in North Korea and would hesitate to push to the brink.

Beijing's ultimate goal has been and would remain so to maintain North Korea as a buffer against US influence and its two Asian allies, Japan and South Korea.

If Trump is frustrated with China's lack of support, will he launch aggressive trade action against China itself which he said he would do soon after assuming power but softened soon enough?

Trump is unlikely to close that option so soon.

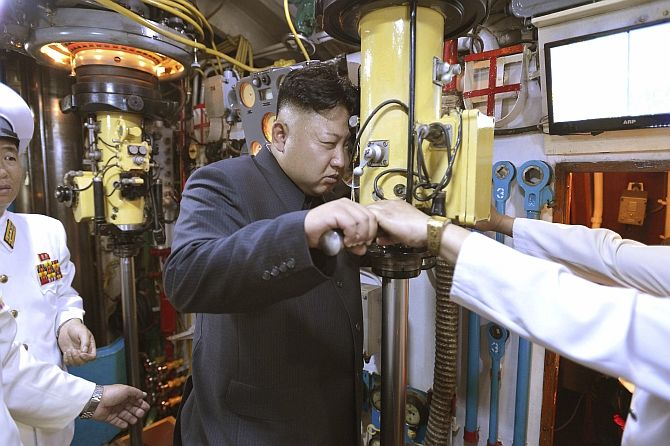

Kim Jong-un watches an army drill. Photograph: KCNA/Reuters

If reports that appeared in the South Korean newspaper, Chosun Ilbo, mentioning some 30 ship-to-ship transfers of oil and other products in international waters between North Korea and China since October 2017 are true, thereby circumventing sanctions, the UN security council's objectives would be rendered rudderless, with no real impact on North Korea.

On its part, China has called on all stakeholders to make constructive efforts in an attempt to ease escalating tensions in the Korean peninsula after Pyongyang reacted to the latest sanctions as an 'act of war' that violates North Korea's sovereignty and tantamount to a total economic blockade.

The UN sanctions could be further crippling if Pyongyang were to carry out another nuclear test or launch another ICBM.

Pyongyang denounced the new punitive measures as a 'pipe dream' for Washington to think North Korea would abandon its nuclear programme.

Much would depend on China.

Beijing has repeatedly urged the involved parties to show restraint and called for peaceful means to resolve this persisting issue through dialogue.

China continues to remain Pyongyang's closest and largest commercial partner, purchasing some 83 per cent of North Korea's exports and selling 85 per cent of the goods imported by North Korea.

Both Japan and South Korea are under constant fear of a North Korean attack. While both are strengthening ties with the US, they are beefing up their own defence capabilities.

There is a view gaining currency in South Korea that North Korea's development of ICBMs is intended to keep US forces at bay and invade South Korea for unification on its own terms.

Having achieved a deliverable capability of a nuclear warhead on a missile, North Korea might be tempted to make an attempt at unification by force with the conviction that the US would be deterred for fear of nuclear reprisal and not risk Los Angeles or other US cities for Seoul.

Such a scenario looks grim, but could be a possibility.

If such is the case, Kim Jong-un would be least bothered if the world recognises North Korea as a nuclear State or not.

If one accepts such a possibility of North Korea wanting to bolster its bargaining power, the argument that Pyongyang is seeking to possess nuclear-tipped long-range missiles for its regime survival loses ground.

Whether one looks at the glass as half full or half empty, the gravity of the situation does not change a bit.

Dr Rajaram Panda is ICCR India Chair visiting professor at the faculty of economics and business administration, Reitaku University, Japan. The views expressed here are personal and do not reflect either that of ICCR or the Government of India.