'If you are so blinded by the Buy American, Hire American policy, if you are not going to be fair, consistent and welcoming, in the end America will lose out.'

Ritu Jha/indica reports from California.

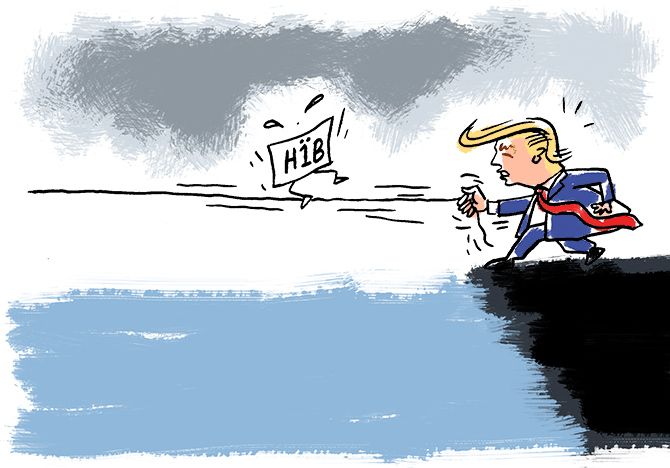

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

Srinivasa Narasimhalu is just one of many Indian software professionals facing harsh scrutiny from the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), but, instead of wilting under pressure, is fighting back.

Narasimhalu -- who was on an H-1B visa -- was employed as a computer professional by Delta Information Systems, Inc and had USCIS authorisation from November 1, 2011 to February 27, 2018. Currently he is out of status.

Michael E Piston, Narasimhalu's attorney, has filed a civil action on the computer professional's behalf in the United States District of Columbia.

Narasimhalu's case exposes a lot of the chaos currently surrounding the H-1B.

A year ago when President Donald J Trump signed the Buy American, Hire American executive order, IT firms did not quite realise he was targeting them too.

That is, till they began getting an increased number of requests for evidence (RFEs) regarding the applicants and the rejections of applications seeking renewals on H-1B visas.

"When he announced it, we thought what has it to do with us, but now this has become a really big problem," Piston told Rediff.com

According to the lawsuit, a professor in the field has evaluated Narasimhalu's education and experience as being equivalent to someone with a bachelor's degree in computer information systems from an accredited institution of higher education in the United States.

But when Delta applied for Narasimhalu using Form I-129, the Petition for Non-immigrant Worker, the USCIS denied the petition.

The agency asserted that there was no employer-employee relationship and that the job of computer systems analyst offered to him is not a specialty occupation.

"My client is a victim of 'Buy American, Hire American'," Piston said.

"In the past we and most other migration attorney have had no problem in getting an H-1B visa approved for a computer system analyst. This was routine. The computer system analyst (application) was thought to be almost automatic. Now we are seeing a 180-degree reversal," Piston added.

It appeared, Piston said, that now many computer system analysts are being denied.

"Now they have started interpreting the law very conservatively. According to this conservative interpretation of law, computer system analysts don't qualify," he said.

According to Piston, the USCIS depends heavily on the Occupational Outlook Handbook, published by the US department of labour.

Going by that, the ultimate question is whether the job demands a bachelor's degree, whether the applicant has a degree or not.

Most computer systems analysts have a bachelor's degree in a computer-related field and that was what mattered before.

Many people qualify for the combination of skills required of a systems analyst, many holding degrees in engineering or statistics and then gaining experience.

This holds not only for people on H-1B visas, but also local applicants.

"What they are doing is interpreting the law very aggressively and very restrictively. (Using) that, they are denying lots of petitions which the USCIS had approved in the past, including those by Narasimhalu," Piston pointed out.

"What makes it more outrageous is that the USCIS (claimed) he wasn't even an employee of his employer," Piston said with a laugh, adding, "In this case they are just making the law up."

The American immigration Lawyers Association's report released last month, Deconstructing The Invisible Wall, covers how things unravelled over the last few months.

According to it, 'On February 22, 2018, just weeks before the opening of the FY 2019 H-1B cap filing window, USCIS released a new policy memorandum imposing heightened evidentiary requirements for all H-1B petitions involving third-party worksites.'

'Without citing specifics, or any data as to the actual rate of confirmed cases of fraud, USCIS claims that significant employer violations are more likely to occur in third-party worksite situations.'

'Employers who intend to place H-1B workers at a third-party worksite have for years been required to submit ample evidence to demonstrate an ongoing employer-employee relationship between the petitioning employer and the H-1B workers.'

'This memo adds even more onerous evidentiary requirements on employers. It also imposes burdensome requirements on third-party companies, which will be called upon to provide contracts, work orders, itineraries, and detailed letters from authorised company representatives attesting to the nature and duration of the project for which H-1B workers are required, even though the third-party company is not the employer.'

'Additionally, when seeking an H-1B extension, employers will be asked to show that the requirements of the H-1B programme were met for the entire previous approval period, effectively requiring documentary evidence of retroactive compliance.'

Cyrus Mehta, founder and managing partner, Cyrus D Mehta & Partners PLLC, echoed Piston when sharing his concern.

"It was not that they were not challenging before, but they are challenging much more now for occupations that are kind of readily obviously recognised for H1B purposes," Mehta said.

He, too, felt the USCIS is not consistent and keep referring to the Occupation Outlook Handbook, which was never designed to address the H-1B visa programme.

"That handbook has been developed for the public to educate them of career options in the US," he said

A USCIS report shows that during fiscal years 2015 to 2018, it sent out 300,762 RFEs for 1.2 million applications.

The number of RFEs served between FY 2015 and FY 2016 rose from 78,469 to 80,961, a non-significant difference, but leaped to 124,237 in FY 2017.

The last number documents a rise of 153 per cent from FY 2016.

In an e-mailed statement (external link) in January to indica, USCIS Director L Francis Cissna conceded there was a change, saying, "It is true that we've issued more RFEs recently. This increase reflects our commitment to protecting the integrity of the immigration system."

"But the RFE rate has not markedly increased and, in fact, has remained consistent over the last few years at around 20 per cent. At the same time, our approval rate has remained above 90 per cent," Cissna said.

"On occasion," the USCIS director added, "it is necessary to issue more than one RFE per petition to ensure the petitioners are being truthful and that the jobs and wages being provided are accurate."

"We understand that RFEs can cause delays, but the added review and additional information gives us the assurance we are approving petitions correctly," Cissna said.

"Increasing our confidence in who receives benefits is a hallmark of this administration and one of my personal priorities."

Asked if any recent changes in the qualifications required for getting an H-1B visa, the USCIS spokesperson said not much.

A specialty occupation requires the theoretical and practical application of a body of highly specialised knowledge and a bachelor's degree or higher in the specific specialty, or its equivalent, as a minimum requirement for entry into the occupation in the United States (for example, architecture, engineering, mathematics, physical sciences, medicine, etc).

Mehta commenting on the Narasimhalu case and hundreds of thousand receiving RFE says they have made the life on H-1B visa more perilous.

"Now even if you have H-1B approved you don't know what is going to happen at time of the extension," Mehta said, again pointing out that Delta had just applied for an extension for Narasimhalu, whose application the USCIS had approved earlier and on the basis of which he had spend years working in the country.

"They (the USCIS) should accept the employer description and not job description," Mehta said.

"If you want to get skilled workers, you have to have reasonable, fair and rational policies. You can't be arbitrary and ad hoc with regards to how you adjudicate these petitions," he said.

Kalpana V Peddibhotla, an immigration attorney, said her team has received several worrying letters, and is sharing these with members of the United States Congress.

Though there are different kinds of RFEs, Peddibhotla said, the most common one involves third-party placement.

"Some of the requirements are beyond what even the regulation would normally require," Peddibhotla said, adding that the USCIS calls for the evidence including people to show a chain of control that many employers cannot provide is causing end clients a lot of avoidable stress.

"The USCIS wants a letter from the end client that acknowledges that H-1B (visa holder) was placed there. That is fine. But then it has to be a specific and exact itinerary," Peddibhotla added.

Such demands have increased in the last year she said, often ending with people being denied extensions.

Mehta said the policy was a definite problem.

"If you are so blinded by the Buy American, Hire American policy, if you are not going to be fair, consistent and welcoming, in the end America will lose out," he said.

"If American companies cannot bring in the workers they want, they will outsource more work to where it is easier to hire skilled people."