Three Indian Air Force officers captured as Prisoners of War by Pakistan during the 1971 War made a daring escape from a Rawalpindi jail. M P Anil Kumar -- our incredible contributor who passed into the ages on May 20, 2014 -- recounts that heroic story.

During the 1971 Indo-Pak war, a watchtower stood prominently near the town of Zafarwal (Shakargarh sector, Pakistan). Tantalised, the Sukhoi-7 fighters of Adampur-based 26 Squadron attacked it umpteen times, the Chandigarh-based An-12 transporters carpet-bombed this area to rubble, but the watchtower defied every IAF raid and stood tall till the cessation of hostilities!

During the 1971 Indo-Pak war, a watchtower stood prominently near the town of Zafarwal (Shakargarh sector, Pakistan). Tantalised, the Sukhoi-7 fighters of Adampur-based 26 Squadron attacked it umpteen times, the Chandigarh-based An-12 transporters carpet-bombed this area to rubble, but the watchtower defied every IAF raid and stood tall till the cessation of hostilities!

Image: A Sukhoi-7 fighter jet. Flight Lieutenant Dilip Parulkar's Su-7 was shot down during the 1971 War. Photograph courtesy: Rakesh Raje/Bharat-Rakshak.com

On December 10, 1971, anti-aircraft guns shot down the Su-7 piloted by Flight Lieutenant Dilip Parulkar close to Zafarwal. He ejected. In fact, he boasts a rare record of three ejections. You count every ejection as renewed life.

Now sample this: In an IAF blitz on an armour column near Kasur in the 1965 Indo-Pak war, his Hunter aircraft took a hit from turret-mounted machine guns; one round pierced the canopy, bored through his right shoulder, missed the head by a whisker. A shave couldn't get closer.

His leader advised him to eject; but he bore the pain and landed the Hunter somehow back at Halwara, his jumpsuit saturated with blood. Post-flight inspection revealed that the bullet proceeded to gash the parachute cords, ie, had he ejected, he would have plunged to earth. A cat with nine lives, kind of 'indestructible' like the watchtower.

But that December he descended into trouble; he parachuted right into the midst of shellacked locals, who roughed him up to vent their spleen. The savage punches on his head caused amnesia; besides the thrashing, he cannot recall the happenings few days before and after the concussion, even today.

His recollection rolls from the solitary confinement and daily interrogation in the PAF Provost & Security Flight (PSF) in Rawalpindi -- a camp for IAF prisoners of war. On the morning of December 25, Squadron Leader Usman Hamid, the camp commandant, invited the POWs over for celebrating Christmas.

The informal atmosphere gave Parulkar and his 11 co-POWs (Wing Commander B A Coelho, Squadron Leaders A V Kamat and D S Jafa, Flight Lieutenants Tejwant Singh, A V Pethia, M S Grewal, Harish Sinhji and J L Bhargava, Flying Officers Hufrid Mulla Feroze, V S Chati and K C Kuruvilla) to huddle and size up the situation. Tejwant broke the uplifting news of the Pakistani surrender in Dacca (now Dhaka); they rejoiced with a dignified hurrah.

Then on, while they had to sleep in their cells, they were free to mingle and spent time together from breakfast to dinner. Awaiting repatriation, they resorted to books, periodicals, cards, chess, seven tiles, volleyball, gossip, even flying kites to kill time. The Red Cross cranked up, its agents appeared monthly to deliver mail and cartons of goodies. To comply with the Third Geneva Convention, they were paid Rs 57 as allowance.

Once while playing seven tiles, Parulkar tripped up, his head bumped into a wall and he convulsed. During this syncopal spell, he uttered 'target' and 'boot' (he lost a boot during ejection); though incoherent, all presumed he had recaptured lost memory, but did not.

Once while playing seven tiles, Parulkar tripped up, his head bumped into a wall and he convulsed. During this syncopal spell, he uttered 'target' and 'boot' (he lost a boot during ejection); though incoherent, all presumed he had recaptured lost memory, but did not.

Left: IAF fighter pilot Dilip Parulkar was held captive along with 11 co-POWs. Photograph courtesy: National Defence Academy

The POWs naturally attracted visitors of every feather. The station commander of nearby Chaklala airbase queried pompously whether they were feeling at home. 'Very much, Sir, this house reminds me of my childhood when I was mostly locked up,' Parulkar retorted. Combative, full of beans.

Meanwhile the air was rife with rumours of repatriation but the limbo lasted long. The already stressed living in captivity was further vitiated by ennui and monotony. Out of the blue, Mulla Feroze was repatriated on medical grounds in February 1972 (Pethia too, but later in July). The monthly allowance came handy to host a modest farewell party.

One ambition monopolised Parulkar's being -- to break out and decamp. Actually, he had broached the idea in end-January, and added that the Geneva Convention commanded a POW to escape and resume duties, for good measure, but everybody laughed out of court and dismissed it as bravado. He hard sold his pet scheme again, singling out Feroze's restoration that the Indian government couldn't care less about the rest.

The slack atmosphere in the camp simply whetted his appetite. Not the kind to retrace, he co-opted Grewal, and his spirited campaign bore fruit ultimately. The consensus was only the duo of Parulkar and Grewal, the fittest two, should endeavour. If caught, the firing squad would be in business.

Parulkar was inspired by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell who masterminded the flight of allied air force servicemen, which became the theme for the famous flick The Great Escape.

Having studied the features of the area, he concluded that unlike the German camp Stalag Luft III, there was no need to dig a tunnel to flee. A barbwire fence separated Cell 4 and the compound of the adjacent PAF recruiting office and petrol pump, and the paved path between the two led to the gate where a corporal was stationed on duty. Dodge the sentries, vault the wall, and you alight on the Mall Road stretch of the legendary Grand Trunk Road.

The first task obviously was to shift into Cell 4. Not just for the relocation, but to meet the other ends too, they had to pal up with the staff, including the guards. Tip for a favour worked in the POW camp too.

Cell 4 was roomy enough to accommodate four cots. Parulkar worked his magic, got Chati, Grewal and himself housed there.

He had hit it off with the camp commandant too. He told Usman he was thinking of touring Europe during the Munich Olympics and that he needed an atlas to map out the sojourn. Some steadfast pestering, and lo, an Oxford school atlas that had seen better days landed on his lap one day.

About this time, Usman had to move out for his new assignment as ADC to the Air Chief. Sqn Ldr Wahid-ud-din assumed charge of the camp. In the hurry, the atlas was left behind.

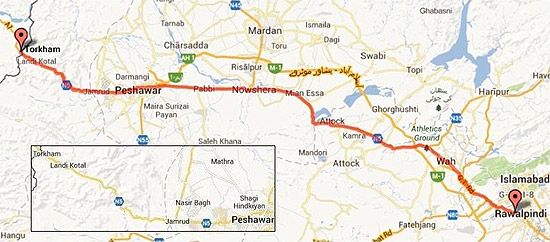

They collectively ruled out the return through Lahore theatre as the front was mined, and would have to wriggle past two armies shooting at each other. It was better to head north, hit the hills, trudge 100-odd kilometres in the easterly direction to touch down somewhere between Uri and Poonch, a less hazardous war zone in their reading. The hardest hurdle of this route was crossing the river Jhelum.

Since the getaway could consume six-seven days, they had to equip themselves with the appropriate survival gear and provisions -- haversack, compass, clothing, footwear, rations, water and cash. The fabric of Chati's parachute canopy was lopped off to stitch two haversacks. The bladders cropped from the G-suit were configured into water-bags. Dry fruits and condensed milk would provide sustenance. Everybody scrimped to pool the kitty.

Kamat contrived a compass, the whole caboodle of component parts tucked up in a hollowed-out pen; a needle balanced on the head of its ballpoint nib oscillated to point at north. This marvel of ingenuity could be clipped to a pocket without arousing suspicion! (How the needles were magnetised, how the pivot, pointer, etc were devised and pieced together, is a story in itself.)

Getting a Pathan suit tailored was no sweat for a person of ample resource like Parulkar. And fortune smiled on him: His parents sent a parcel containing two shirts and a pair of trousers. The logistics were taken care of.

In the meantime, Harish was bitten badly by the escape bug, but was found wanting in every criterion -- fitness, features, not to speak of his ability to converse in Urdu/Hindi/Punjabi -- but he made up with enthusiasm what he lacked in attributes. He was smuggled in and occupied the fourth bed almost unnoticed.

Parulkar & Co had worked on a window and its grille, had loosened it enough to dislodge it with a shove, but unluckily the guards discovered it at the eleventh hour and refastened it. Their questioning stares were parried with we-don’t-know shrugs.

One morning the camp commandant burst in slapping a newspaper, fumed that a Pakistani POW was gunned down in India, gestured he too could be trigger-happy, threatened tit-for-tat and hotfooted out. The message was loud and clear, but nothing could deter Parulkar. In fact, he was immersed in plotting his next move.

On the wall opposite the barbed wire, he marked a rectangular outline above the skirting-board, to scrape and de-brick the area to burrow a hole whose perimeter would be just enough for one to slither through.

While the quartet whiled away the daytime playing bridge, Parulkar and Grewal burned the midnight oil to beaver away with filched tools like table knife, iron nails, screwdriver and scissors, and Harish kept an eye out for spoilers more so because the alley beside the cell was a regular beat of the warders.

They concealed the 'escape hole' with a blanket draped over the bedstead, and humoured the sweeper to shirk. Come morning, the debris was whisked off into the cartons.

The duo then dredged out the mortar, detached the bricks one by one, and left the outer plaster intact. The 'escape hole' was ready on July 27.

They attempted to escape the next night, but could not demolish the exterior. Their exertions produced a gaping fist-sized orifice only! The plaster was not a coat but a thick layer of firm cement. They replaced the loose bricks and cursed.

The Rawalpindi-Torkham escape route; courtesy: Google Maps

The Rawalpindi-Torkham escape route; courtesy: Google Maps

Not the hiccup but the fear of detection of the baby-hole was what had them on tenterhooks. Luckily, not a soul -- not even those who parked their bicycles alongside the wall -- noticed the odd cavity. While the night birds unpacked the toolkit and got down to chipping off the periphery, Harish stumbled on valuable information: A bus service at night.

Given the short haul, they could reach Peshawar before daybreak. He scrutinised the map. The town Torkham on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, it struck him, was only 34 miles from Peshawar. Lurk till nightfall, sneak in to Jamrud along the railway line, hoof it into the hills of Landi Kotal, wend their way to Landi Khana, hah, there you are, nine furlongs shy of the border at Torkham. Could breathe free air before the search-and-nab-contingent got wind of their scent. Voila! Why not skedaddle to Afghanistan?

Since Grewal was laid low by a bout of indisposition, they had to bide their time. The night of August 12 augured auspicious as a few events concurred: since it intervened the holidays of Friday and August 14 (Pakistan's Independence Day), the weekend endured and a relaxed mood pervaded the camp; Wahid-ud-din retired to a Murree resort; a storm began brewing by evening (would keep the sentries indoors).

The plaster yielded, the trio crept out singly. They threw the Uri-Poonch map about the recruiting centre as red herring. Parulkar glanced at the wristwatch: half past midnight (August 13). The rain was beating down. Soaking in the downpour, shod in canvas shoes, the heroes paced down the windswept Mall Road towards the highway, what they hoped were the first footsteps of their march to freedom.

A scalp disease had compelled Grewal, a Sikh, to razor the locks; the one-inch regrowth lent him a pukka Pathan mien. The threesome, now on a trek to touristy Khyber, assumed their pseudonyms: Parulkar and Grewal were PAF airmen John Masih and Ali Ameer respectively, and Harish, their drummer friend, mutated into Harold Jacob.

They boarded a Peshawar-bound bus an hour later, but the busman kept the engine idling till the vehicle filled up. As he revved up, the conductor tapped Harish's shoulder and asked for the fare in broken English, not Urdu. That they stood out even in the dead of night shook them into acute self-consciousness.

The psychology of an escapee gripped them. Did they have a fighting chance to breast the tape at Torkham?

At the crack of dawn, the bus entered Peshawar city limits. They got off, ambled to a roadside tea shop. Since they wanted to reach Jamrud road before the dawn brightened into broad daylight, they got going on shank's mare into the marches of Pathan country, where every second adult toted a gun and belted up a bandolier. (Dressed to kill, eh?)

As they took in the sights and sounds, Grewal, their 'Pathan' hailed a tonga. The tongawala grilled Grewal, so much so the 10-minute ride on the carriage appeared to last an hour. They were relieved to rid him off their back and head to Jamrud road as indicated by the nosy fellow.

The next strand of their egress was to find the railway line to Jamrud and linger thereabouts until sundown. Jamrud road was lined with shops and habitation; every mortal goggled at them, making them edgy with acute self-consciousness; they had no choice but to keep their head down and to carry on footslogging.

The road forked left, they followed this branch and found the railway line, but the piercing gaze of the onlookers prodded them to backtrack and pursue the old course. They were, however, elated to discover that the railway ran parallel to the road.

As they totted up two hours of legwork they espied a tollgate where checking was on. Parulkar, the bellwether, took stock: Further walking was unsafe. They hovered until a bus arrived, climbed atop and blended with the dozen-odd passengers already ensconced on the roof. The bus, after being searched at five or six checkpoints, rolled in to its destination. Jamrud ahoy!

Back at the camp, Chati made three dummy beds, masked the hole, sanitised the cubicle and strove to feign signs of life in the cell. He flashed thumbs up when the remaining seven gathered for breakfast. They maintained 'radio silence' thereafter. What befuddled them was no one bothered finding out why the three were still asleep.

Had the heroes been hooked, was the indifference a mere charade? They chewed on, with bated breath...