The remarkable story of Wing Commander Rakesh Sharma, the first Indian in space, will be seen in a film featuring Aamir Khan.

The retired cosmonaut and test pilot tells Archana Masih why he doesn't like being called a hero.

Exclusive to Rediff.com

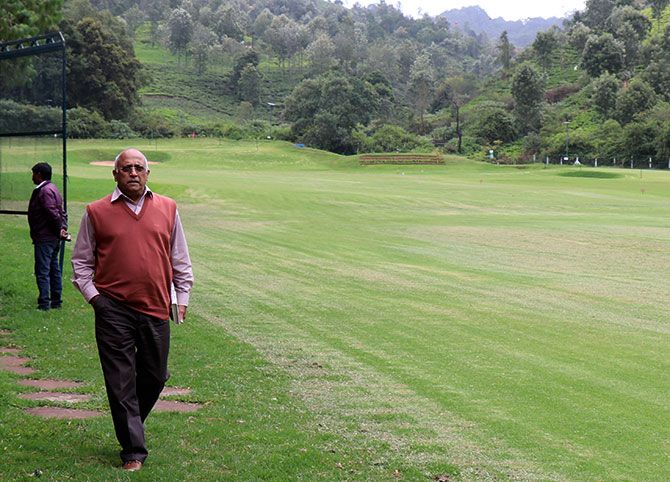

In 1984, he became the first Indian in space. Photograph: Rajesh Karkera/Rediff.com

As the interview concluded, the young man sitting with his family at the next table, came over to ask who I was speaking to.

We were at the Wellington Gymkhana Club, overlooking the lush greens as players finished a morning game of golf on a crisp Saturday morning. Steppes of tea bushes gradually rose up to meet the hills of the Niligiris on what was a perfect day.

"Wing Commander Rakesh Shar..." I had barely completed the name that the man and his wife raced towards the parking lot, hoping to catch India's first and only man in space, before he drove off.

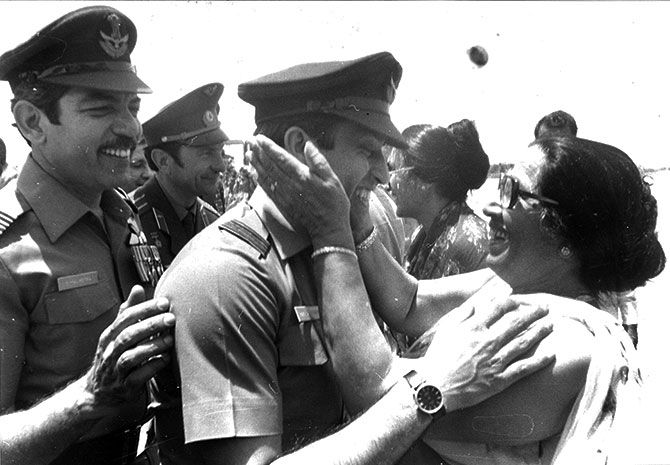

They did and returned jubilant to the table where juice, snacks and child had been hurriedly left behind to meet the dignified former fighter pilot, a veteran of the 1971 War, a space voyager and recipient of the Ashok Chakra, India's highest honour for valour in peacetime.

"It was a dream come true," gushed the lady introducing herself as a scientist as she returned to the table, "I wanted to be an astronaut, but I couldn't. I tell my daughter she must fulfill my dream."

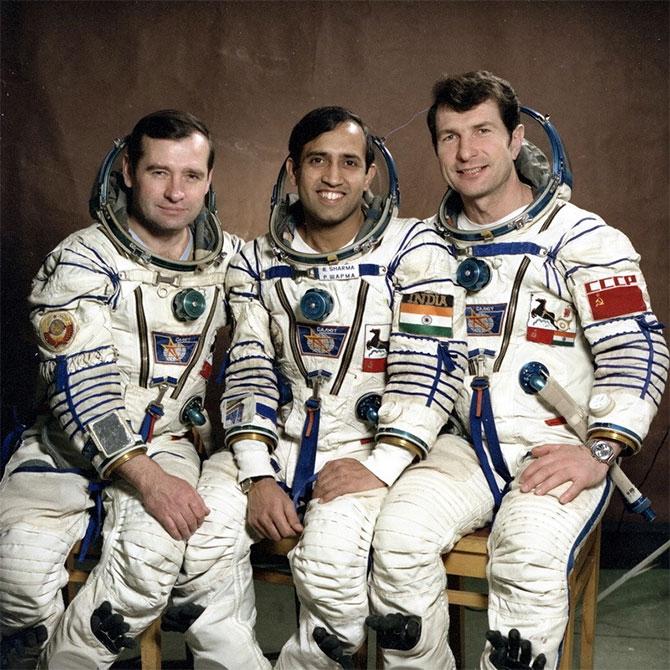

The cosmonauts were launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in present day Kazakhstan in a Soviet Rocket Soyuz T-11.

Photograph: Kind courtesy Spacefacts.de

Thirty-three years after he spent eight days in space, Wing Commander Rakesh Sharma, 69, draws similar adulation from generations of Indians who have memories of watching him inside that Russian shuttle on their television sets in April 1984.

But the reticent test pilot does not make a fuss about the space journey.

"I have difficulty reconciling to an event which in my opinion was rather routine. Any other person from the air force or the services could have done it. I believe the response is not commensurate with the event," he says with humility, his forehead furrowing into a frown, then making way for a hesitant smile.

"Agreed, I am the first Indian, but I would argue that it was taking a ride in somebody else's technology? Had it happened, as it is likely to happen in 5 to 8 years, when Indian astronauts go on ISRO's launchers that would be something."

The words are said with a flourish of the hand, a voice laced with pride as if he was imagining that day in front of his eyes.

Wing Commander Sharma is understated about his accomplishment but then there are others who think otherwise. A film on his life will go on the floors next year. Aamir Khan will play the cosmonaut who made history.

After being approached ten years ago, he wrestled for three years before finally consenting to the biopic.

He is uncomfortable about having the spotlight back on him, but since he is no longer in uniform and lives in a small town, he feels he will be able to manage his privacy.

"I have met Aamir. I am sure he will portray the protagonist convincingly given the fact that he is such a consummate professional."

It so happens that the actor's cousin Mansoor Khan, director of Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, Joh Jeeta Wohi Sikandar, Akele Hum Akele Tum and Josh also lives in the same town. Mansoor gave up filmmaking and moved to Coonoor to start a home stay and make cheese.

Almost a decade ago after retiring as a test pilot from the Indian Air Force, Wing Commander Sharma settled in Coonoor, away from the crowd, noise and exposure of city life.

He fell in love with these hills as a 15-year-old boy on his first solo trip to visit an uncle after finishing Senior Cambridge in Hyderabad.

The second time he travelled alone and far was when he left home for the National Defence Academy in Khadakvasla, Pune. A year after he joined the IAF in 1970, India and Pakistan went to war.

He flew several missions in his MiG-21, but is reluctant to reveal his experience because it is part of the biopic.

"Today, the war comes into your living room, at that time there was no TV, telephones. It is only after the war got over that one realised what a good drubbing we gave and of course, it was exceptional planning," he recalls.

It turned out to be a pleasant coincidence that the land he bought in Coonoor was contiguous to the post-retirement home of Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, who set incomparable standards of military leadership as commander-in-chief of the Indian Army in that war.

"I have never had the privilege or honour of meeting him. By the time I moved to Coonoor, he was not doing too well and passed on."

Uncomfortable about being called a hero or seen as someone who did something extraordinary, it was hard for Wing Commander Sharma to come to terms with public adulation initially.

"It is something I have never gotten used to. I still am not. But I do realise that it's a role that has been given to me and I understand that people are curious."

"It is necessary to knock the stardust and glamour off subjects which are going to be a part of life of the current generation," he laughs, saying people's interest in him was because the subject of space is so universally captivating.

"I was a student when Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space in 1961, and I lapped every written word."

"From 1962 to 1984 Life magazine, and others had started unraveling space, so it wasn't as if I was pushing off into the unknown."

One would assume that he would rate being the first Indian in space as the pinnacle of his achievements, but he begs to differ.

"I'm not being facetious -- I'm not putting it down or downplaying it. As a test pilot, I faced more challenges. Most armed forces personnel don't beat their chests about what they have done and achieved. It's another day at the office," he says putting it in perspective by adding that 127 men had successfully travelled to space before him.

"In test flying you don't know what awaits you round the corner. You fly with fate, you address all the 'What ifs' and try to stay ahead of the curve every time and therein lies the challenge," he says with the easy laugh of a seasoned professional.

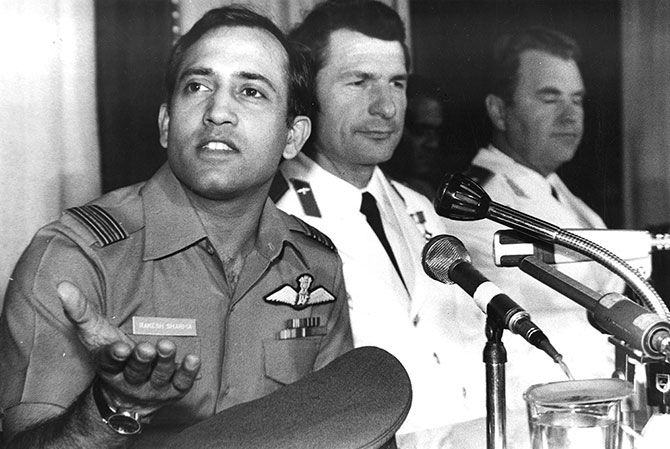

SEE: The famous 'Saare Jahan Se Accha' moment with then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

The preparation for the space journey had taken two years, including a year in the Soviet Union. "It was expensive stuff, there were a heap of experiments to do, each minute was calibrated, it was not a fun trip, it was work," he remembers.

While on earth -- in India -- it was a moment of national triumph that brought young and old in front of their television sets. When he told then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in a news conference, that India looked 'Saare Jahan Se Accha' from space, it had a staggering country-wide impact and became the defining moment of his space journey.

"Some people feel deeply touched, shed a tear or say how proud they are of him and relive the moment when they heard him say 'Saare Jahan Se Accha," daughter Krittika Sharma, a senior design associate and behaviour architect, says in an e-mail.

The other common questions, she says, her father is regularly asked are:

'If Saare Jahan Se Acch was rehearsed or did it come naturally?'

'What did India look like from space?'

'Given the chance, would he go back to space?'

'Can he still speak Russian?'

'Is he in touch with his crew?'

Wing Commander Sharma drove across the Eastern United States to raise awareness about missing children while participating in the Fireball Run in 2015.

Photograph: Kind courtesy The Fireball Run/Facebook

Looking back at that moment, Wing Commander Sharma says he was informed of the video link to the prime minister two days before the event. He was also told to take the camera around the spacecraft to show the rest of India what it looked like.

"Quite like what Sunita Williams did," he says. "I met her when she visited India."

But he had no idea what the PM would ask.

"Which is why the grammar was all wrong," he laughs. "When we were in school we used to sing the song all the time so it was top of recall. And the fact is that both India and Africa looked brilliant from space."

After his return, he continued his test pilot career, subsequently moving to the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited where he was chief project pilot for Tejas (the light combat aircraft) for six years.

"Then I outgrew that project, the aircraft wasn't ready and I had crossed 50," says Wing Commander Sharma who continued testing aeroplanes till he was 53 and retired at 60.

SEE: The space hero on his life in space and after. Video: Rajesh Karkera/Rediff.com

The Wellington Gymkhana founded in 1873, harks back to days of the Raj, when Wing Commander Sharma's ancestors lived quite literally on the other side of India, in Multan, West Punjab, present day Pakistan.

"I always say I was born in the first half of the previous century," he laughs and recounts the courage with which his family rebuilt life in post-Partition India.

"My parents restarted life with one steel trunk. My mom were eight sisters and no brother. They were educated which ran against the grain of society at that time, but it made them employable and jump-started their interrupted lives."

"My mother knew the value of education and attempted to give us the best of education. That's how life unfolded and we got back on an even keel."

Looking into the expansive greens with golfers and caddies about their play, he says he had a wonderful journey and if had to be born again he would repeat it.

He spends the day reading, writing, gardening and preparing for talks, for which he travels twice a month.

"It isn't as if I have closeted myself. I try my best to share my experience. Just as I was motivated when I was young, you really don't know what will be the trigger that will set you going."

Daughter Krittika is a behavioural consultant, son Kapil is a Bollywood director whose debut film was I, Me aur Mein.

We are at the end of the conversation and he looks at his watch, telling me he has to meet his wife for lunch. I ask if it is true that he and his interior designer wife built their home in just 9 months.

"Eleven," he corrects me. The bricks came out of the soil and were baked in the sun, wooden beams support a tiled roof, there is solar heating, plenty of natural light and rainwater is harvested.

Tucked away in a corner of his study is his space memorabilia, the Ashok Chakra medal and citation.

"I don't like to display it," laughs the officer-gentleman-icon as he walks away from the greens.

"I am a back-bencher."