Toral Varia and photographer Reuben Verghese, who travelled to the Naxal-infested Keonjhar district of Odisha, return with tales of discrimination, disillusionment and daring escapes

Read Part 1 of the series: Disillusioned, Naxals give up violence in Odisha

In the last seven months, the Odisha government, the state police force and paramilitary personnel have been breathing a little easier.

For, they have finally taken some successful strides in the tribal-dominated and Maoist-infested district of Keonjhar in northern Orissa.

As many as 21 Naxal rebels have given up their arms, two key state committee members of the Communist Party of India -- Maoist have been killed in encounters and several key arrests have been made in the last seven months.

Along with a growing disillusionment with the party, cadres from Orissa also feel the pinch of discrimination, as the top brass is dominated by Naxal leaders from Andhra Pradesh.

According to the intelligence gathered by anti-Naxal agencies, ever since the merger of the Maoist Communist Centre and People's War Group, there have been reports of a deep and widening fissure between the cadres of Orissa and Andhra Pradesh.

"The surrendered rebels as well as the arrested party members have confessed that they were disillusioned at the way they were being undermined and misused by their Telugu leaders and comrades," says Ashish Singh, superintendent of police, Keonjhar district.

'Maoists bargained only for the release of Telugu leaders'

Image: Superintendent of Police Ashish Singh (left) and interlocutor Dandapani MohantyThe various divisions of the CPI-Maoist are headed by leaders from Andhra Pradesh. None of the 41 central committee members are from Odisha. Some educated members, like Sabyasachi Panda, reach the second highest level of becoming a state committee member.

Singh points out, "This difference was evident even during the recent abduction of the Malkangiri district collector and his junior. The Maoists bargained for the release of only the Telugu leaders. No Oriya leader's name was mentioned during the negotiations, not even Sabyasachi Panda's wife Subhashree, who is currently in jail."

But his claims are dismissed by Dandapani Mohanty, who was the chief interlocutor during the Malkangiri kidnapping incident (in which collector R Vineel Krishna and junior engineer Pabitra Majhi were kidnapped in Orissa on February 16).

He says, "All this is the creation of the state and corporate machinery against the revolutionary movement. If you look at the Malkangiri incident, the delay was more due to communication gap as against the contrary belief of discontent between the Telugu and Odisha cadres."

Mohanty may believe otherwise, but cracks within the CPI-Maoist run deep, right from the top level party leaders to the foot soldiers.

"There is so much discrimination that even the food prepared for Telugu and Oriya cadres varies. Basic amenities like food, clothing, medical assistance are not distributed equally. Surrendered Naxals have told us that while distributing uniforms, the Telugus are given preference over their Oriya counterparts. These instances have led to dissent within the party, resulting in a rise in the number of those who chose to surrender," says Singh.

'Food and living conditions were really bad'

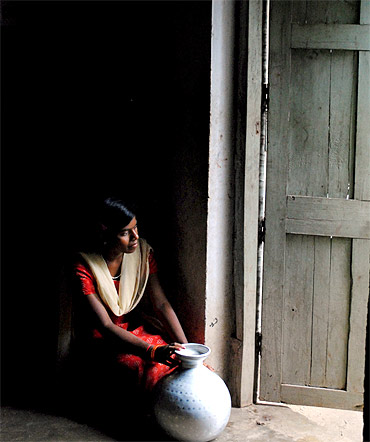

Image: Jayanti MahantaPhotographs: Reuben Verghese/Rediff.com

According to an officer from the Special Operation Group, "There have been instances when disillusioned party members themselves give us tips because they are frustrated with the stagnation within the party. Telugu leaders assign party members to collect funds, but none of it is shared with the party members who live in deplorable conditions. Even during encounters, only Oriya members are sent to the firing line, while their Telugu counterparts are involved in planning and strategising."

The discrimination against Naxal cadres from Orissa is sharp, blatant and demoralising, as 18-year-old Jayanti Mahanta found out the hard way.

Jayanti Mahanta alias Seema was a resident of Galda village in Keonjhar district. In 2008, Jayanti was handpicked by a group of three rebels -- Bobby, Bonzi, and Sunil -- who visited her village often.

Jayanti, who was living with her stepmother, could not get along with her family.

"I would regularly get beaten up by my parents or fight with them. I had even consumed poison when I was in 7th standard. They (the party members) were aware of my problems and convinced me to join the party with the promise of a better life," she says.

But it was not long before reality dawned on Jayanti.

"The food and living conditions were really bad. There was no hygiene. There was no proper place to sleep. We would keep moving from one village to another. Within three-four days of joining the party my body started aching. In the name of food, they would give us leftovers that were brought from the village homes. I hated it. Someone or the other was always down with malaria. Leeches used to suck our blood. Despite my differences with my parents, I was used to eating fresh and warm food. My health started deteriorating. But what could I do? I did not know anyone. I did not know where I was. I had no option but to quietly resign myself to the situation," recalls Jayanti.

'They worked only for themselves'

Image: Sadhu MahakudPhotographs: Reuben N V/Rediff.com

As if in a trance, Jayanti continues, "I remember the Telugu cadre used to talk among themselves, saying, 'What will we do? If the policemen come for us, she will not even be able to run. She will put all of us in trouble.' They thought I did not understand Telugu, but I did."

While Jayanti struggled to adjust to the sordid living conditions, 17-year-old Sadhu Mahakud alias Baji, another young Naxal cadre, started having serious misgivings about the senseless violence perpetrated by the outfit's leaders.

A resident of Kainsinali village in Keonjhar district, Baji did not want to join the party, but was forcibly taken away.

"During the four years of my association with the party, I saw that they were indulging in violence with the villagers. They worked only for themselves; no one was working for the cause. My resolve to leave the party became even stronger," he said.

Baji tried to escape from the camp thrice and finally succeeded in doing so in his fourth attempt. But every time he got caught, he was threatened that he would get killed in a fake encounter, or the police would implicate him in false cases.

"Worse still, they told me that the police would cut off my hands and legs and sprinkle salt and chilli powder on the wounds. I was scared. But I knew I had to get out of that place," says Baji.

Long, candid chats with former cadres like Jayanti and Baji -- both of them surrendered to the state police this year -- give one a glimpse of the highly disciplined and extremely secretive world of Naxalism.

'Every time I read about an attack, we would all clap'

Image: This is where the surrendered Naxals livePhotographs: Reuben N V/Rediff.com

Once in the party, the recruits are given new names, clothes and identities for strategic purposes. With a new name, there is no apprehension of another recruit spilling the beans on his fellow members as no one is aware of anyone's real identity.

In the event that a recruit rises within the ranks, he can evade law enforcement and anti-Naxal agencies with the help of his assumed identity.

So Jayanti Mahanta became Seema and Sadhu Mahakud became Baji from the day they joined the Lal Salaam brigade.

All the new recruits are made to compulsorily perform sentry duties. Area commanders of different squads would assign duties to the party members.

Jayanti and Baji both belonged to the Harichandanpur squad because both were residents of Harichandanpur area in Keonjhar. Every morning their area commander Sadhu would assign duties like fetching newspapers, getting medicines, purchasing groceries and collection of funds.

Jayanti, who had cleared her 9th standard, was assigned several roles. She was the newspaper reader, school 'master', and a 'doctor' before finally joining the 'assault team'.

"Every day I would read articles related to the party from the newspapers to the group. Every time I read about an attack on the police by our fellow cadres, we would all clap and shout," says Jayanti.

'When I fired I hit the bull's eye'

Image: Jayanti MahantaPhotographs: Toral Varia/Rediff.com

Because Jayanti had had basic education, initially she was asked to teach the other cadres during study hours. But she felt bad doing so. "I used to wonder, what is my qualification to teach anyone anything? So I asked for my duties to be changed." Soon, she was made the 'doctor' of Harichandanpur squad. Jayanti did not like performing these duties either. Fed up with her chores, one day as a challenge, she took up firing a weapon.

Even today, when she talks about her weaponry skills, she beams with pride. An animated Jayanti says, "They thought what could a tribal girl do, but when I fired I hit the bull's eye! After that, whenever an attack was planned, I would be included in the assault team. Sadhu would be the first commander and I would be right behind him."

She was soon given the charge of party's Nari Mukti Sangathan in the Harichandanpur area.

When she surrendered in July this year, Jayanti confessed to her role in the murder of one Salku Hembram under the Ghasipura police station, an attack on Bunu Paikray at Sansialimal, Trinath Mohanta at Rebana Palaspal, and the beat house in Simplipal.

Meanwhile, Baji worked as a 'doctor' and was also in charge of cultural programmes. He knew nothing about medicines, says Baji, but "over a period of time I was given training in how to give injections, which medicines to be given for which symptoms and in administering basic first aid. But for serious injuries, the patient had to be taken to the village."

Baji was trained by Basant aka Susheel, secretary of the Kalinganagar division. According to the intelligence inputs, Susheel, originally a resident of Andhra Pradesh, is a qualified pharmacist. He has prepared a detailed paper on the use of basic medicines which is followed by every recruit who is trained to be a 'doctor'.

Almost every other evening Baji and his fellow comrades would sing songs or perform a dance to impromptu tunes for poems and songs written by party leaders. Remembering one of those evenings, Baji breaks into one of the most popular song among the cadres, "Hay madal bajila re ghoomra bajila re, aamey sabu bhai attu birsa mudaro chel re, Asso hay luliya chaasi, asso hay bharatvasi, birsa munsar pori ladiba dhanura dhori, Lal pathaka ku dhori aamey bojouy heba re (We are all disciples of the great warrior Birsa Munda, Oh farmers and countrymen, let us unite and fight till we hoist the red flag).

'I am now an expert in preparing IEDs'

Image: Sadhu MahakudPhotographs: Toral Varia/Rediff.com

Typically, a day in the life of a rebel begins at 5 am. From 6 to 8 in the morning the entire platoon would go trekking, mountain climbing, and perform exercises and train in guerrilla tactics. From 8 to 10 am the group would take a break for 'tiffin' (breakfast).

During the first tiffin break, area commanders would delegate duties to different cadres. From 10 am to 1 pm, everyone would attend classes where the cadres would listen to Maoist literature, followed by another 'tiffin break' (lunch). After some rest, selected cadres would train in firing and handling of arms and ammunition.

"I am now an expert of sorts in preparing and using IEDs, landmines, cleaning and loading of weapons, and firing. Everyone who was physically fit had to undergo the training," says Jayanti.

During their training, the cadres' only motto was Maribu poche daribu nai (will die but not be scared.) They were taught to confront the policemen and not withdraw.

Baji too had to undergo training but was never given key roles in the execution of an operation. "I would only get a katta (country-made revolver). Most of the time, I was given sentry duty during operations. We would move from village to village very often. I would carry loads on my shoulders during the move," recalls Baji.

Whenever an operation was being planned, the leader would give precise and clinical instructions to party members. Each stage of the operation would be delegated to a particular cadre, almost like an army operation.

Baji's list of crime includes an attack on a development project handled by Gayatri Constructions, a blast in Phandi, and setting ablaze a liquor shop in his village.

'I hid in a pit till nightfall'

Image: The police quarter inside the Keonjhar Reserve Police grounds where the surrendered Naxals have been accomodatedPhotographs: Reuben N V/Rediff.com

Despite the momentary kick of successfully executing operations and garnering praises from their party leaders, life was not what was promised to them. There were several like Baji and Jayanti who were unhappy.

"But who would dare to talk openly about it? You never know who would report to the leader about our intention to get away," says Baji, who himself tried escaping thrice in a span of three months before finally managing to break free.

Baji got lucky around April 1 this year. He was sent to his own village with some work, where he saw a police party patrolling the area. He seized the opportunity and ran to his home. Baji's father convinced him to surrender before the local police authorities.

Jayanti's escape saga reflects her courage and determination.

As a rule, the Naxal platoon would not camp around any village for more than three or four days. Bathing was considered a luxury too. One day, around mid-June, the platoon was camping around a village where the women were allowed to go and take a bath one by one.

Jayanti was supposed to relieve her co-cadre Rashmi who was on sentry duty. But taking advantage of the situation, she insisted Rashmi go and take a bath first.

"I was scared. Once Rashmi left, I quickly changed into my dress and discarded the pant-shirt I was given to wear. I even left a note on a weapon stating, 'I don't like the party, I don't like the party work. So I am leaving', and ran to a nearby village and hid in a pit till nightfall," says Jayanti.

'They leave behind posters threatening to kill'

Image: The district police headquarters, where the surrendered Naxals are first brought toPhotographs: Reuben N V/Rediff.com

Under the refuge of the dark, Jayanti managed to reach home, but within minutes of her arrival, she saw 7-8 party members approaching her house.

"I told my stepmother not to tell the Maobadis (Maoists) that I have come here or they will kill her too, and hid on a tree nearby," says Jayanti.

Before leaving, the Naxals had threatened her family so strongly that they didn't want to take her back. Her father told her point blank to return to the party, but a head-strong Jayanti would not agree.

"I pleaded with my father that I don't want to go back. I told him that if he doesn't want to take care of me then he should tell me straight. I told him I am educated and I can take care of myself and left home. I had nothing with me. I climbed Saroi Ghati and spent the night there. In the morning I ate a packet of biscuits, drank water. I was not sacred of the jungle. I was used to it. I kept walking and climbing, and eventually reached Juhanagar basti. I practically begged for food and continued walking till I crossed the mountains and reached the Andhra side of the border. I started living there. I would occasionally visit home, but ensured that people do not get to know about it. If the party members came to know about it then they would have killed me and my family," says Jayanti.

Finally, it was her elder sister and her grandmother who spotted her near Bhadrak railway station when she was returning from Andhra Pradesh and convinced her to surrender before the local police.

Baji and Jayanti and several others like them are still staying in the temporary quarters allotted to them within the reserve police premises in Keonjhar.

"I miss my family. I go and visit them occasionally. But I have to be very discreet about it. The Maoists have come home several times asking about me. They leave behind posters and pamphlets threatening to kill those who have surrendered," says Baji.

The rift between the two factions of the party and increase in the statistics of surrendered rebels is good news for the state government. And while it's okay for the state to take advantage of the widening cracks in the CPI-Maoist, it's equally important to whip up political will and set rolling the wheels of development in these rural areas. Perhaps that will stop more Bajis and Jayantis from picking up arms to fight illusory battles.

In the third and last part of the series, read about the fascinating journey of a former Naxal area commander who is today a successful Home Guard with the Keonjhar police.

article