Why has China suddenly ratcheted up tension with India over Arunachal Pradesh? Claude Arpi, who has written extensively on Tibet, offers an insight.

Repeated Chinese intrusions into Indian territory, veiled threats to 'split' India, and a constantly aggressive stance on Arunachal Pradesh have recently got a great deal of coverage in the Indian media.

The worst was perhaps the threatening tone of the Chinese press. The Global Times objected to Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh's visit to Arunachal: 'Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh made another provocative and dangerous move. India will make a fatal error if it mistakes China's approach for weakness. The Chinese government and public regard territorial integrity as a core national interest, one that must be defended with every means.'

Why has the Chinese leadership suddenly become so aggressive about Tawang and Arunachal Pradesh?

In a recent interview, Professor Wang Dehua, director, Centre for South Asia Studies at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, stated that India would 'just' have to surrender the Aksai Chin plateau in Ladakh and Tawang and the border issue could be solved.

Why this obsession with Tawang and the Land of Dawn-lit Mountains?

The core issue is the fact that Tibet was an independent country when the misnamed People's Liberation Army marched into Tibet in October 1950. This can be proved without ambiguity by digging into the British Archives in London (or the almirahs of our ministry of external affairs).

One example: Noel-Baker, the British foreign secretary, addressed the House of Commons on December 14, 1949, to inform the MPs about the British official stand on Tibet. London stood by a memo given by Prime Minister Antony Eden to Dr T V Soong, the Chinese foreign minister, in 1943.

It stated: 'Since the Chinese Revolution of 1911, when Chinese forces [which had occupied Tibet for a short time] were withdrawn from Tibet, Tibet has enjoyed de facto independence. She has ever since regarded herself as in practice completely autonomous and has opposed Chinese attempts to reassert control.'

Interestingly, when the British high commissioner in India showed this to K P S Menon, the first Indian foreign secretary, he said: "Such publicity is good". India agreed and wanted the world to know about Tibet 'de facto' independence.

Unfortunately, less than a year later, Chinese troops entered Tibet and began to occupy the entire plateau.

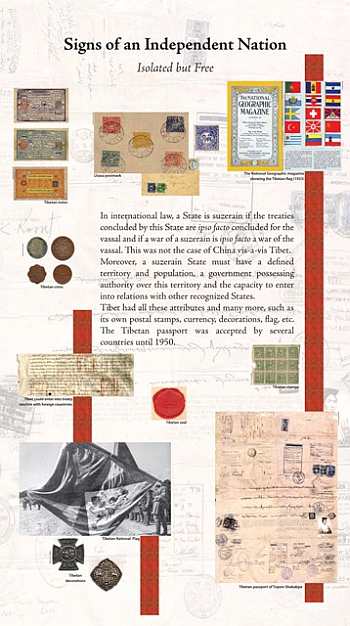

Over the last nearly six decades, Beijing has done its utmost to make the world forget that before 1950 Tibet was an independent state with not only a separate language, literature, religion and culture, but also its own foreign office, currency, coins, stamps and even hand-made paper passport.

Beijing has practically succeeded in erasing all these factors from the world's collective memory, but for one thing: a thick red line.

This last symbol, the McMahon Line, proving that Tibet could sign treaties on its own, delineated the Indo-Tibet border. Beijing believes that if by a magic trick (or a bit of bullying), it can manage to annul the red line, nobody could ever challenge China's colonisation of Tibet anymore; the last proof that the powerless religious nation was invaded by its neighbour would disappear.

This is the crux of the matter and explains Beijing's present anger and belligerence.

In 1903, British Viceroy Lord Curzon cabled London that 'the Chinese suzerainty over Tibet was a constitutional fiction'. He proved his point a year later by sending to Tibet a military expedition under Francis Younghusband.

The young colonel discovered what Curzon knew, that there was no Chinese presence in Lhasa. While the Chinese were unhappy that the truth had emerged, the British, as usual, wanted to remain fair.

The solution found by the British was to convey a Tripartite Conference in Simla in 1913 to get an agreement between China, Tibet and themselves on the 'constitutional fiction'. The main bone of contention at that time was the border between Tibet and China.

While discussions were going on about the Tibet-China differences, Sir Henry McMahon and his Tibetan counterpart, Lochen Shatra, sat separately to delineate the Indo-Tibetan border.

On March 24, through an exchange of notes between the British and Tibetan plenipotentiaries, the Indo-Tibet frontier was fixed. McMahon wrote to Shatra: 'The final settlement of this India-Tibet frontier will help to prevent causes of future dispute and thus cannot fail to be of great advantage to both governments.'

The next day, the Tibetan plenipotentiary replied: 'As it was feared that there might be friction in future unless the boundary between India and Tibet is clearly defined, I submitted the map, which you sent to me in February last, to the Tibetan government at Lhasa for orders. I have now received orders from Lhasa, and I accordingly agree to the boundary as marked in red in the two copies of the maps signed by you.'

The British and the Tibetan delegates signed and sealed the map. Thus the McMahon Line was born as a red line demarcating the Indo-Tibetan boundary in the eastern sector.

Today, Beijing is not ready to accept the McMahon Line as it would be a de facto recognition that an accord signed by an independent Tibetan government has legal validity.

Did the Chinese always claim Tawang? The answer is, 'No'.

During the 1950s, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai was ready to accept the McMahon Line as the border between 'China's Tibet' and India.

A letter from the then Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru to U Nu, his Burmese counterpart, is revealing. On April 22, 1957, Nehru wrote: 'I am writing to you immediately so as to inform you of one particular development which took place here when Chou En-lai [Zhou Enlai] came to India.

'In your letter you say that while Premier Chou En-lai was prepared to accept the McMahon Line in the north [of Burma], he objected to the use of the name 'McMahon Line', as this may produce 'complications vis- -vis India', and therefore, he preferred to use the term 'traditional line'.'

Nehru continued: '[Zhou] said that while he was not convinced of the justice of our claim to the present Indian frontier with China (in Tibet), he was prepared to accept it. That is, he made it clear that he accepted the McMahon Line between India and China, chiefly because of his desire to settle outstanding matters with a friendly country like India and also because of usage etc. I think, he added he did not like the name 'McMahon Line'.'

Nehru had some doubts that he had heard properly what the Chinese Premier had said: 'I wanted to remove all doubts about it. I asked him again therefore and he repeated it quite clearly. I expressed my satisfaction at what he said. I added that there were two or three minor frontier matters pending between India and China on the Tibet border and the sooner these were settled, the better. He agreed.'

Zhou however told his Indian counterpart that after the signature of the Panchsheel Agreement on Tibet in 1954, the Tibetans objected to the demarcation of the line: 'The Tibetans wanted us to reject this Line; but we told them that the question should be temporarily put aside. I believe immediately after India's independence, the Tibetan government had also written to the Government of India about this matter. But now we think that we should try to persuade and convince the Tibetans to accept it.'

The forthcoming visit of the Dalai Lama to Tawang is another occasion for the Tibetan leader to reiterate that he has always stood by the McMahon Line and Zhou's argument (which the Tibetans objected to) does not stand.

Another misconception created by the Chinese is that because Tsangyang Gyatso, the Sixth Dalai Lama, great poet and lover, was born near Tawang in 1683. For Beijing, it is proof that Tawang belongs to Tibet (and therefore part of China). Elementary, Mr Hu!

This is another lame argument. Is France part of Kashmir because Dr Karan Singh was born in Cannes on the French Riviera? What about Liaquat Ali Khan, born in Karnal, Haryana; Zia-ul-Haq was born in Jalandhar; or Pervez Musharraf in Daryaganj in Delhi? Does it make Haryana, Punjab or Delhi a part of Pakistan?

The Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyaltso (the Precious Ocean of Pure Melody), who loved freedom above all, would have probably written a beautiful poem on Chinese pretentions.

Chinese names

The Chinese say that all the names south of the McMahon are Chinese. Unless Tibetan language (gompa, dzong, la, chu, etc) has become Chinese, it is wrong. In fact both languages are etymologically and grammatically totally different. However, if the Chinese start claiming as theirs all the areas using 'Bothia' (Tibetan) language and scripts, Kinnaur, Lahaul, Spiti, Ladakh or Sikkim will soon be claimed by them. And why not the Buriat and Kalmyk republics of the Russian Federation? What about Darjeeling (from Tibetan Dorjee Ling, meaning the place of the Vajra)? Does it make sense?

The current campaign is primarily caused by the forthcoming visit of the Dalai Lama to Arunachal Pradesh which in itself is a reiteration that the Tibetan leader stands by the McMahon Line as the Indo-Tibet border, a historical fact which can't be erased retrospectively.