A 60-page report by the Human Rights Watch titled 'Between Two Sets of Guns: Attacks on Civil Society Activists in India's Maoist Conflict', documents human rights abuses against activists in Orissa, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh.

This is part two of a three-part series:

Part 1: Why activists live in fear of govt and Maoists

The Indian government should:

Promptly and transparently investigate alleged abuses against civil society activists, and prosecute those responsible as appropriate.

Investigate the role of senior police and administrative officials in the commission of or failure to prevent abuses; take appropriate action against those responsible, including disciplinary measures, such as removal from office, and criminal prosecution.

Instruct police to end the practice of arbitrary detention and strictly implement the D K Basu guidelines on arrest and detention issued by the Supreme Court. Initiate disciplinary action against police officers who violate the guidelines.

End the practice of filing politically motivated criminal charges and instruct prosecutors to dismiss criminal charges where the evidence is not sufficient to support the charges.

Instruct national and state officials not to treat critics of the government and civil society activists as Maoist supporters. Instruct officials to stop discrediting rights organisations and activists through unfounded public accusations of complicity with the Maoists, which undermines their work and places them at serious personal risk.

Repeal the colonial-era sedition law used to silence peaceful political dissent in violation of Supreme Court rulings. Drop all pending sedition cases.

The Communist Party of India-Maoist should:

Cease all reprisals against people who work on government development projects and their family members. End obstruction of development efforts, since this only harms marginalised and deprived communities.

In recent years, the Maoist movement has spread to nine states in central and eastern India. The Maoists have a significant presence in the states of Chhattisgarh, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Bihar, and West Bengal, and a marginal presence in Assam, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh.

The Maoists assert that they are defending the rights of the marginalised: The poor, the landless, the Dalits, and tribal indigenous communities. They call for a revolution, demanding a radical restructuring of the social, political, and economic order.

The Maoists believe the only way marginalised communities can win respect for their rights is to overthrow the existing structure by violent attacks on the state.

Various state governments have responded to this challenge by carrying out security operations to defeat the Maoist movement, provide protection for local residents, and restore law and order. The police in these states receive support from central government paramilitary forces.

Various state and national forces often conduct joint operations, in part to deny the Maoists sanctuary in other states. Because of the ineffective response by states, in 2009 the central government started to coordinate security operations.

...

In 2006, the Congress Party-led government decided to adopt a two-pronged approach to the renewed rise of the Maoists. First, the government would increase and speed up efforts at economic development and social justice to win local support. Second, it would deploy security forces to counter the Maoists.

The government has deployed thousands of federal paramilitary police, such as the Central Reserve Police Force and the Border Security Force, to support state police forces. It has resisted calls to deploy the army, although the army has provided training in guerrilla warfare to these forces.

In 2008 the government created the Commando Battalions for Resolute Action. COBRA consists of 10 battalions (approximately 10,000 troops) of special forces trained and equipped for counterinsurgency and jungle-warfare operations. It operates as part of the CRPF.

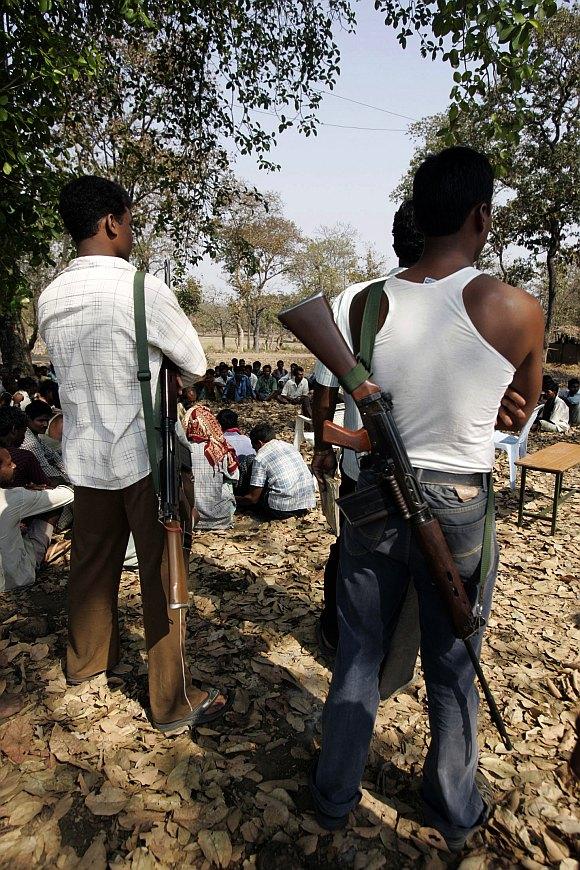

In Chhattisgarh, the government in 2005 embarked upon a plan to involve civilians in fighting the Maoists, setting up a group called the Salwa Judum to raid villages believed to be pro-Maoist. The Police Act of 1861 allows states to temporarily employ civilians as Special Police Officers.

In essence, SPOs have the same powers as regular police, but do not receive proper training. The Chhattisgarh government recruited large numbers of SPOs, all of them Salwa Judum supporters, seeking to use their extensive knowledge of the terrain for combat operations.

The Salwa Judum and SPOs were responsible for serious human rights abuses. Security forces often joined Salwa Judum members on village raids, which were designed to identify suspected Maoist sympathizers and evacuate residents from villages believed to be providing support to them.

The Salwa Judum and the SPOs engaged in threats, beatings, arbitrary arrests and detention, killings, and burning of villages to force residents into supporting Salwa Judum and relocating to government camps. They also coerced camp residents, including children, to join in Salwa Judum's activities, beating and imposing penalties on those who refused.

Tens of thousands of villagers were displaced and forced to move into government shelters. Others escaped into the forests in neighboring Andhra Pradesh.

In July 2011, the Supreme Court in a public interest lawsuit ordered the disbanding of the Salwa Judum on the grounds that it was unconstitutional. It ordered the government to 'immediately cease and desist from using SPOs in any manner or form in any activities, directly or indirectly, aimed at controlling, countering, mitigating or otherwise eliminating Maoist/Naxalite activities'.

The Maoists assert that while inequality and lack of development gave rise to their movement, current government efforts are merely a 'developmental mask to their fascist repressive measures'.

Mining-company-initiated projects accompanied by forcible land acquisition and displacement of villagers, or otherwise perceived as threatening villager well-being, have fuelled local resentments. The Maoists' strategy has been to disrupt state attempts at delivering development by targeting infrastructure such as telecommunications towers and roads.

They also attack police stations, state infrastructure, politicians, and persons they claim are public enemies. Many observers agree that the Maoist rebellion has drawn attention to the plight of the communities and forced the government to try and improve living and economic conditions.

Prior to the Maoist movement, tribal community members say, they had no rights or control over the forest, were forced to sell their produce to contractors at low rates, and faced abuse or extortion at the hands of money-lenders, contractors, and those few low-level government officials who did bother to venture into forest areas.

...

Villagers are caught between Maoists and the security forces, both of whom demand loyalty and information. Both claim to be acting to protect the local population, but both often take harsh measures against villagers as retribution for what they see as villager support for the other side or inadequate support for their side.

In its submission for the Universal Periodic Review at the United Nations Human Rights Council, the government said that 464 civilians and 142 security forces were killed by Maoists in 2011, and most of the victims belonged 'to poor and marginalised sections of society'.

According to data compiled by the Institute for Conflict Management, nearly 1,200 people, half of them civilians, were killed in 2010, while around 1,000, including 391 civilians, were killed in 2009. According to the ministry of home affairs, over 3,000 people have been killed in the conflict since 2008.

The government's security response to the Maoists has resulted in serious human rights violations. Villagers, mostly from tribal communities, have been arbitrarily arrested and detained, tortured, and extrajudicially executed. In Chhattisgarh, the Vanvasi Chetna Ashram has filed 522 complaints of abuses by government forces, including murder, rape, beatings, and arson.

Local jails are packed beyond capacity as hundreds have been arbitrarily arrested. At least 600 people, most of them tribal villagers, are in jail in Orissa, accused of being Maoists. In May 2011 the Orissa high court ordered compensation in the cases of Gangula Tadingi and Ratunu Sirika, who died in custody, finding that the prisoners did not receive proper medical treatment.

Unable to locate Naxalite fighters who hide in the forests and ambush soldiers on patrol, security forces have retaliated against civilians suspected of being Maoist supporters. In some cases, government security forces have burned down huts and beaten villagers in retaliation for Maoist ambushes.

An inquiry was ordered by the Chhattisgarh government after allegations that security forces had attacked the villages of Tadmetla, Morpalli, and Timmapuram on March 16, 2011, burning down huts and raping and killing villagers.

Activists condemned the killing of 20 people in Chhattisgarh in June 2012. Security forces had initially claimed to have killed Maoists, but after it emerged that a number of those killed were innocent villagers, Home Minister P Chidambaram said, "If any innocent person has been killed, I am deeply sorry." An inquiry has been ordered and the National Human Rights Commission has called for a detailed report.

In remote forest areas in central and eastern India, Maoists have also committed serious abuses, such as targeted killings of police, political figures, and landlords deemed deserving of punishment.

...

In some cases, individuals are brought before a jan adalat, or people's court, where the Maoists conduct public trials to punish enemies or 'offenders'. Wealthy landowners are brought before a jan adalat and asked to hand over a portion of their assets for the poor.

Those who refuse are beaten after the conveners of the jan adalat have sought and received the approval of the gathering. Suspected informers are beheaded or shot, sometimes after they are sentenced in a jan adalat.

These courts, which are of course illegal as a matter of domestic law, fail all international standards of independence, impartiality, competence of judges, the presumption of innocence, and access to defense.

The Maoists have acted with extreme brutality. In October 2009 they abducted and killed police official Francis Induwar in Jharkhand, leaving his decapitated body on the national highway. In Gadchiroli in Maharashtra state at around the same time, after 18 police officers were killed in a Maoist ambush, the Maoists beheaded suspected police informer Suresh Alami.

In November 2010, Maoists left a warning poster after chopping off the arms and legs of a man allegedly found to be an informer by a jan adalat in Jharkand's Giridh district. In March 2012, Maoists abducted two Italian tourists and an Orissa legislator, demanding release of their supporters as ransom.

In April 2012 Maoists abducted Alex Pal Menon, the district administrator of Chhattisgarh's Sukma district, and demanded a halt in security operations.

The Maoists often oppose government development efforts and target individuals implementing such schemes as alleged government agents. In Orissa, according to state police, at least six contractors have been killed for implementing infrastructure projects since 2010.

The Maoists have also been responsible for extortion and demanding shelter and intelligence information from civilians, placing them at risk. They have attacked schools and health facilities, directly targeting and blowing up government buildings.

The Maoists claim that they only attack structures being used by government forces, but Human Rights Watch research shows that they also target structures not being used or occupied by security forces.

The Maoists routinely recruit children between the ages of 6-12 for combat operations through children's associations called bal sangams, in which children are indoctrinated with Maoist ideology, used as informers, and trained to fight with non-lethal weapons (such as sticks).

The children, once they join armed units, are not permitted to leave and in the case of noncompliance face severe reprisals, such as the targetted killing of their family members.

The Maoists obtain firearms and other weaponry and ammunition by looting police armories and making purchases on the illegal market. They also make and use explosive devices.

Government security forces and Maoists rebels engaged in armed conflict seem to have one thing that unites them: a dislike for local activists who criticise their policies or practices. Both have acted against members of civil society, harming individuals working for the public good, and perpetuating a pervasive climate of fear.

Activists, by the very nature of their work, need to travel to remote areas where they might come upon Maoists and work out practical arrangements. They also routinely engage with various government officials to ensure effective implementation of development policies.

Both sides nonetheless respond to these realities by accusing activists of acting as informers or being secret members of the other side. Himanshu Kumar of the Vanvasi Chetna Ashram, an NGO that works on tribal welfare, described the situation in a 2009 interview:

The Naxalites were cautious of us, it was never a complete 'go ahead' from their side. They would stop us at times, but the people for whom we worked were in complete support, they liked us. The Naxalites would accuse VCA of being with the government, saying, "The VCA is implementing government programs here, we don't want them here." ut our tribal activists would speak for us.

"This is for our children, you can't stop them." And the Naxalites had to compromise. Lastly they said, "The VCA doesn't have political ambition, so we won't disturb them." The government says that the VCA is pro-Naxal. Government officials had taken to corruption a long time back, and we intervened. The schools were non-existent even before the Naxalites came into the picture, so the government has always been unhappy with us. So they call us 'Naxalites'.

Read the third and final part of this report tomorrow.

...