Illegal mining has been a hot debating point for the past couple of years. In Karnataka especially, the scam is of such magnitude that many powerful persons have had their heads on the chopping block and in the months to come there will be many more to follow. In this two-part series, Rediff.com's Vicky Nanjappa takes a close look at this dirty scam, which spreads across various parts of the country, especially in Goa and also Rajasthan.

The HRW on last Thursday put out a very detailed report on illegal mining. Although the earlier reports which were put up by various agencies dealt a lot with the corruption aspect, this one sought to detail the lack of regulation in the mining industry which has been the primary reason for corruption.

Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director at the HRW takes rediff.com through the report.

The mining industry in India has become an important part of the economy, but the flip side to it is that it has become a hazard thanks to the absence of regulation. There is a dangerous cocktail of bad policies, weak institutions, and corruption, government oversight and regulation of India's mining industry is largely ineffectual.

The fact that in the year 2010-2011 mineral worth Rs 200,000 crore was produced in India goes on to show what a booming industry it has been. The Indian government has fixed its sights on a 9 per cent rate of economic growth and many planners view continued expansion of the mining sector as essential to any hopes of hitting that target.

On a more human scale, India's mines provide direct employment to several hundred thousand people and indirectly help sustain the livelihoods of many thousands more.

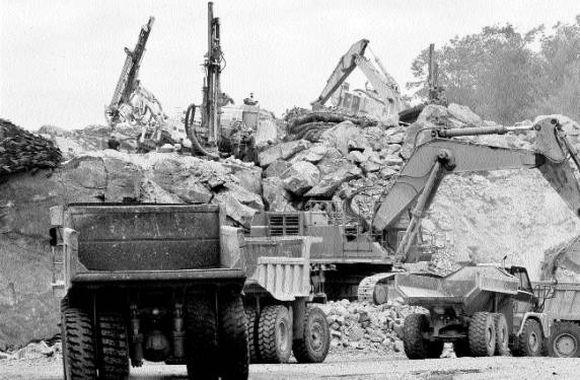

Mining can be a uniquely destructive and dangerous industry if not managed and regulated responsibly.

Critics have long alleged that the push for industrialisation and growth "creates pressure (on regulators) to look the other way" instead of demanding that mines and other industrial projects adhere to the law.

India has some 2,600 active mines and for every mining megaproject that attracts widespread civil society criticism and press attention, there are hundreds of smaller mines that do not attract much scrutiny outside of the local populations they impact directly.

Their cumulative impact is enormous but, as this report shows, the government has completely failed to ensure that those mines are run responsibly and to prevent them from harming the communities around them.

...

India's mining sector is rife with illegality, some of it viscerally shocking and some of it relatively arcane. The most brazen criminality involves the extraction of minerals from land that a mine operator has no legal right to work on, commonly referred to as 'illegal mining'."

In some cases, this takes place hidden deep in isolated forests, or centers around rapid fly-by-night operations with only a handful of machines and laborers working in a very small area.

Because even the smallest mines and quarries are difficult things to hide, operators of such mines often develop corrupt relationships with public officials who are happy to look the other way.

With rising global prices, however, other minerals including iron, manganese and coal are increasingly being looted in the same way.

The two case studies in this report focus on two different facets of India's mining chaos. The mining mess in the iron-rich state of Goa offers a clear window into the human toll of a broader institutional breakdown of regulatory machinery that plagues India's entire mining sector.

The lurid mining scandals in Karnataka State reveal the mutually reinforcing impacts of an out-of-control mining industry and pervasive rot and corruption in public institutions. These problems are two sides of one coin, each reinforcing the other.

...

Goa is far better known for the two million vacationers who throng its beaches every year than for its iron mines. But starting just a few kilometers inland from its coastal resorts, the state has about 90 working mines that yielded some 45 million tonnne of iron ore in 2010 -- 20 per cent of India's total.

Goan iron was worth well over Rs 21.5 crore ($5 billion) in 2011 and production has skyrocketed in recent years in response to rising global prices.

The State government officials estimate that the mining industry directly employs some 20,000 people and indirectly supports the livelihoods of tens of thousands more.

Goa is a tiny state and many of its mines are clustered closely together and directly adjacent to nearby communities. The local industry is dominated by three large firms that all have their roots in the state: Fomento, Salgaocar and Sesa Goa; the last of which was acquired by mining giant Vedanta in 2007.

The mining industry in Goa stands as a stark example of the broader patterns of regulatory collapse described later in this report. Surprisingly, when Human Rights Watch put these allegations to key state government and industry officials, many acknowledged that they were true.

A senior official with one of Goa's top three mining companies, speaking on condition of anonymity, put it this way, "There is a total lack of governance in the mining sector. The government has no idea what is going on.... Absent a real change in governance, there will just be more corruption and more chaos from year to year."

Even mining industry spokesman S. Sridhar estimated to Human Rights Watch that 40 percent of all mining operations in Goa fail to comply with at least some laws and regulations and that perhaps another 5 per cent is entirely illegal, taking place on land miners have no right to work on.

"The remaining mining is done legally," Goa Environment Minister Alexio Sequeria told Human Rights Watch he thought the true figures were less alarming but added, "He (Sridhar) should know better than me."

P S Banerjee, general manager for Fomento, one of Goa's 'big three' mining companies, told Human Rights Watch that his company's own operations were meticulous in adhering to the letter of the law.

But speaking of the industry more broadly, he said that "Mining in Goa works in shades of gray. The problem is not just legal versus illegal mining, but there is a huge gray area in between and that is the most important issue."

Banerjee described this approach to the law euphemistically as 'creative compliance.'

On paper, Goa's Pollution Control Board has the responsibility to verify whether mining companies (and other industries) are complying with India's air and water acts.Those laws are important tools to help ensure that mines do not cause serious harm to human health and the environment. But in practice, the board is ineffectual and carries out little meaningful oversight activity of mining or any other industry.

As of late 2011, the board had only 16 technical staff to oversee the environmental and pollution-related practices of the entire mining industry as well as of every other business in the state -- including even visiting cruise ships.

Then-Goa Environment Minister Alexi Saqueria was dismissive of the board's oversight role, calling it a 'mere post office' that did little more than ferry paperwork between the central government and operations based in Goa.

...

Goa's mines department tracks production figures based entirely on figures submitted by mine operators themselves. The department had only 12 technical staff as of September 2011 and Dr Hector Fernandez, the department's senior geologist, conceded to HRW that the government had no way of verifying whether company figures were accurate.

"With this staff we cannot," he said, "It's impossible." This means that the state does not actually know if mines are producing ore in excess of what they claim, thereby cheating the government out of tax revenue and royalties. Critics allege that this is precisely what has taken place.

A September 2011 report by the Goa legislature's Public Accounts Committee detailed what it called unexplained discrepancies between production and export figures. Those could translate into steep revenue losses for the state government, since no royalties or other taxes would be paid on unreported production.

Industry officials questioned the figures, arguing that there could be benign explanations for many of the apparent discrepancies. Alarmingly, the state government could neither confirm nor deny the allegations because it did not have any data of its own.

Central government failures

The Indian central government imposed a moratorium on new mining leases in Goa in February 2010, apparently at the request of the State government. However, this did not result in remedying deficiencies with the clearances underpinning the state's existing mines.

Many of Goa's mines appear to have been established on the basis of Environmental Impact Assessments that contained erroneous or fabricated data.

In theory, the environment ministry's regional office in Bangalore monitors whether mines in Goa and neighboring states are operating in compliance with the law and with the terms of their environmental clearances -- and can shut them down if they are not.

But in practice, regional office staff rarely visits the state and have never halted the operations of any mine in Goa.

...

Many Goan mine operators are increasingly reliant on contractors to operate their mines or transport their products to the port. Encouraged by the vast profits being made in the mining sector, Goan politicians have gotten in on the mining business by becoming contractors themselves.

The trend towards using contractors is driven largely by economic considerations -- labor costs are lower and companies do not wish to invest heavily in new equipment that may lose its value if commodity prices and iron production decline.

But in some cases, there is also a political calculation. Some contractors are hired because their ties to politicians make them better able to either navigate or evade the regulatory framework, not because of their competence or reputation for responsible operation.

Officials with two different Goan mining firms, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Human Rights Watch that companies often selected contractors with political ties for the wrong reasons, and that contractors linked to politicians often displayed little interest in working responsibly or even obeying the law.

"Sometimes you proactively go to a politician and say, 'Look, let's do this together,' so you get it done faster," one company official said, adding that he disapproved of the practice.

"Politicians have entered into this mining business and are spoiling the names of established mining companies. Their actions tar the reputation of the whole industry."

Jaoquim Alemao, until March 2012 Goa's politically influential Minister of Urban Development, started a company called Rhissa Mining Services. The company is run by his son. The former minister does not deny his involvement in the mining business and says that Rhissa's only role is to purchase heavy machinery and rent it out to established mining firms, which is not illegal.

Some observers have raised concerns about the true nature Rhissa's activities. Rama Velip, a farmer and anti-mining activist in the south Goa village of Rivona, says he was approached by a representative of Rhissa who attempted to persuade him to abandon his opposition to nearby mining developments -- mines that Rhissa had little or no clear economic stake in.

Local activists also allege that police officers also profit from the mining industry by purchasing trucks they contract out to haul ore from mine sites -- creating a conflict of interest when local protests shut down a mine that helps supply their income.

South Goa's cluster of iron mines is relatively new, with most springing up within the last 10 years (modern, mechanised mining has been taking place in north Goa for several decades). Human Rights Watch visited mining-affected communities in south Goa's Quepem taluk (district) and found evidence that some communities are suffering precisely the kind of harm that government regulation of the industry is supposed to prevent.

The mostly agricultural communities in south Goa are profoundly divided in their attitudes towards the industry. Residents who allege that mining has destroyed vital groundwater supplies, ruined crops and created serious health risks have protested strenuously against local mine operators.

On the other side of the divide, villagers who have derived direct economic benefits from mining activity -- often by purchasing trucks they hire out to haul ore away from the mine sites -- have emerged as ardent proponents of the industry.

...

Some residents of mining-affected communities told Human Rights Watch they worried that dust emissions from passing ore trucks could be linked to respiratory disease in their communities.

"People are getting breathing problems," one farmer complained. Hundreds of heavily laden ore trucks pass through narrow roads leading through those communities every day, spewing clouds iron-rich dust as they pass. According to residents, the dust settles in thick coats on the crops that stand in nearby fields, on homes, and even on a schoolhouse that sits adjacent to the road.

Some communities in Goa resort to making use of surface water for at least part of the year because their groundwater supplies have been damaged or destroyed by nearby mining operations.

Water and agriculture

People living in and around two south Goa villages visited by Human Rights Watch --Rivona and Caurem -- complained that adjacent mines have polluted nearby rivers and streams through irresponsible waste disposal and that natural springs used to irrigate fields have been destroyed as mines puncture the water table and damage aquifers.

"Because of water pollution, there is no water for agriculture," said farmer and anti-mining activist Rama Velip. "Some wells are dry. Some spring water is destroyed."

Most mines in Goa operate below the water table, and many are forced to continually pump out vast quantities of water in order to keep mine pits dry.

Often, mine operators simply discard the water rather than reinject it into the ground to help regenerate the resource.

Many of these claims are impossible to verify because sufficient data does not exist—and that is part of the problem. Public officials have done nothing to study alleged harms caused by the cumulative impact of mining operations in south Goa, and do not know how many mine operators are engaged in irresponsible and illegal practices that could bring about such harm. The data that does exist, however, is troubling.

Threats and violence

There have been occasional reports of violence and direct threats against anti-mining activists in Goa. Nilesh Gaukar, a resident of Caurem village who helped organise local anti-mining protests in 2011, told Human Rights Watch that he received an anonymous phone call in early May warning him that 'mine owners and contractors' were planning to attack him.

On May 12, as he alighted from a public bus at the nearby industrial estate where he worked, a man wielding an iron bar attacked him:

I got off the bus and as I was going to the gate someone hit me with an iron rod. Ten or 15 people were around (but) he got away on a motorcycle -- one person was waiting there on the bike. I saw him get on the bike and flee. He tried to get me on the head but only got me on the shoulder and elbow.

Gaukar spent four days in the hospital and when he returned home, police officials in Quepem provided him with a 24-hour police guard. No one was arrested.

Another prominent local voice against mining, Cheryl DeSousa, told Human Rights Watch that she has suffered a long string of phone calls threatening violence against her and her daughter in extremely graphic terms.

DeSouza owns more than 200 acres of farmland in the heart of south Goa's iron mining belt and has participated in anti-mining protests by nearby villagers.

DeSousa says that she has been approached with highly lucrative offers to buy her land but has consistently refused, partly because her late husband is buried there. She told Human Rights Watch that because of her refusal to sell, she has received numerous threatening phone calls from anonymous callers.

Dhe said that some have threatened to gang rape her teenage daughter and throw acid on her face. "They also told me that my problem is that I haven't had a man in so long, and they will fix that." She did not file a complaint with the police, describing that as a 'waste of time'.

...